I’m a populist, yet I advocate the life of the mind. I’d like to see less elitism (of certain kinds) along with more intense and widespread intellectual inquiry. Unfortunately, the most prominent varieties of populism today are anti-intellectual. This is a problem rooted in social structures. Some of the solutions involve changing the way formal educational institutions work. Others involve enhancing intellectual life in informal contexts.

Let’s define “anti-intellectualism” as a rejection of advanced, specialized, complicated thought, which is viewed as antithetical to common sense. According to Mark Fisher (The Washington Post 7/17), Donald Trump is an explicit anti-intellectual:

He said in a series of interviews that he does not need to read extensively because he reaches the right decisions “with very little knowledge other than the knowledge I [already] had, plus the words ‘common sense,’ because I have a lot of common sense and I have a lot of business ability.” Trump said he is skeptical of experts because “they can’t see the forest for the trees.” He believes that when he makes decisions, people see that he instinctively knows the right thing to do: “A lot of people said, ‘Man, he was more accurate than guys who have studied it all the time.'” … Trump said reading long documents is a waste of time because he absorbs the gist of an issue very quickly. “I’m a very efficient guy,” he said. “Now, I could also do it verbally, which is fine. I’d always rather have — I want it short. There’s no reason to do hundreds of pages because I know exactly what it is.”

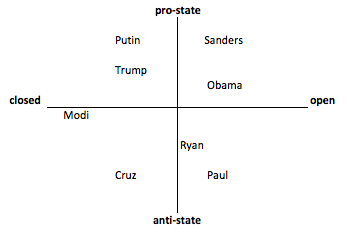

Presumably, Trump’s anti-intellectualism was more of a political asset than a liability in the campaign, and that tells us something about our culture. (On the other hand, one of the most curious and thoughtful political leaders in modern America–and a very fine writer–won the two previous presidential elections, so politics is not a vast wasteland.)

Let’s define “anti-elitism” as a rejection of the superior position, entitlement, and power of some privileged group. This is different from anti-intellectualism because an elite needn’t be defined by knowledge or expertise: the business class, for instance, usually is not. However, the two ideas often come together, not only in Trump’s rhetoric but in many other examples from American history. For instance, in Anti-Intellectualism in American Life (1963), Richard Hofstadter wrote:

The kind of anti-intellectualism expressed in official circles during the 1950’s was mainly the traditional businessman’s suspicion of experts working in any area outside his control, whether in scientific laboratories, universities, or diplomatic corps. Far more acute and sweeping was the hostility to intellectuals expressed on the far-right wing, a categorical folkish dislike of the educated classes and of any thing respectable, established, pedigreed, or cultivated. The right-wing crusade of the 1950’s was full of heated rhetoric about “Harvard professors, twisted-thinking intellectuals … in the State Department; those who are “burdened with Phi Beta Kappa keys and academic honors” but not “equally loaded with honesty and common sense”; “the American respectables, the socially pedigreed, the culturally acceptable, the certified gentlemen and scholars of the day, dripping with college degrees .. . the “best people” who were for Alger Hiss”; “the pompous diplomat in striped pants with phony British accent”; those who try to fight Communism “with kid gloves in perfumed drawing rooms “; Easterners who “insult the people of the great Midwest and West, the heart of America; those who can “trace their ancestry back to the eighteenth century or even further” but whose loyalty is still not above suspicion; those who understand “the Groton vocabulary of the Hiss-Achcson group.”

The businessmen who distrusted independent intellectuals represented one elite quarreling with a different one–Wall Street and Detroit struggled for influence with the Ivy League and the State Department. But the “far right-wing” rejected elites that they defined in terms of social privilege rather than intellectualism. For these people, the problem with Groton School alumni was not their sophisticated ways of thought but their social pedigree and arrogance. These right populists were against Wall Street and Harvard. Although Hafstadter is writing here about the right wing, some left populists share the same targets.

I think anti-elitism and anti-intellectualism come together because educational institutions serve two functions simultaneously.

On one hand, schools and colleges are spaces for intellectual inquiry. They are the most prominent and best supported places where people address unanswered questions of public importance, conduct deep and sustained conversations about unresolved topics, and model and teach the skills and values required for those pursuits.

At the same time, schools and colleges confer social status. A college degree is a prerequisite for occupying many of the advantaged slots in our social order. Educational institutions at all levels teach not only intellectual skills, but also manners, modes of social interaction, and ways of writing and speaking that mark out the advantaged class. And despite their protestations that they admit students fairly, they are dominated by children of privileged groups. For reasons that I’ve explored in some length, I don’t think this situation is likely to change markedly.

To make matters even more fraught, the genuine search for knowledge can be conducted arrogantly or else responsively. One can pursue the truth by studying other people and their problems in order to change those people (for good or ill), or one can listen and create knowledge together. Finally, claims to advanced knowledge can be trustworthy or not. After all, highly credentialed experts are the ones who told us to blast highways through inner cities, minimize fat consumption, and invade Iraq.

I think several trends worsen the conflation of populism with anti-intellectualism today.

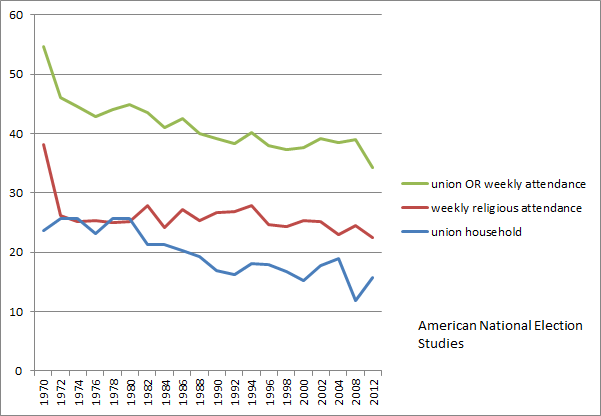

First, although advanced intellectual inquiry occurs in some spaces that aren’t educational institutions–community organizing groups, online magazines, some religious communities, and hip hop–the state of “informal” intellectual life does not seem to be strong today compared to the past. Most of the people who can spend a lot of their time reading, writing, and talking about complex issues work as teachers or professors.

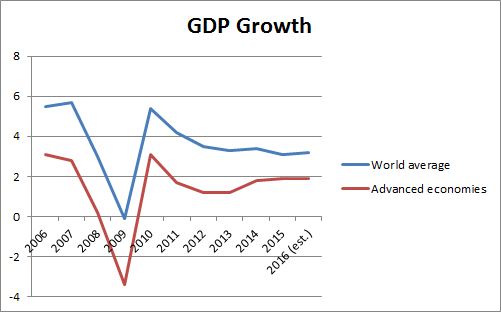

Second, tools for data collection, analysis, and influence are giving frightening amounts of power to people who possess and deploy information.

Third, in a post-industrial economy, the workforce is increasingly divided between people who work with their hands in low-status roles, and others who work with symbols and data. The former understandably wonder why they must pay for the latter, whether directly or via taxation. University of Wisconsin professor Kathy Cramer describes how she would visit small towns in her state and introduce herself “as a public opinion scholar from the state’s flagship university.” When she asked citizens what concerned them most, they often “expressed a deeply felt sense of not getting their ‘fair share’ …. They felt that they didn’t get a reasonable proportion of decision-making power, believing that the key decisions were made in the major metro areas of Madison [where Kathy works] and Milwaukee, then decreed out to the rest of the state, with little listening being done to people like them.” It became clear to Cramer that when they complained about people who didn’t work hard enough, they were “talking about the laziness of desk-job white professionals like me.” Why did their tax dollars have to pay for someone to drive around the state asking people political questions so she could write her books?

Finally, today seems like a time of growing deference to high-status people. As I wrote last fall:

We live at a time when billionaires, celebrities, and CEOs are given extraordinary deference, especially in comparison to run-of-the-mill elected officials, civil servants, union leaders, and grassroots organizers. Politicians, for instance, are constantly in contact with their wealthiest constituents. First-year Democratic Members of the House are advised to spend four hours per day of every day calling donors. Meanwhile, many advocacy groups are funded by rich individuals, not sustained by membership dues, so their leaders are also constantly on the phone or at conferences and meetings with wealthy people.

One solution is to identify, strengthen, and lift up informal spaces where people who haven’t attended college–at least, not recently–engage in intense intellectual work. When I interviewed the great community organizer Ernesto Cortés, Jr. (Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF) co-chair and executive director of the West / Southwest IAF regional network), he told me this was his organization’s strategy:

Building talented, committed, enterprising relational organizers through recruitment, training, and mentoring. We develop their capacity to be reciprocal, relational organizers. Ask–what do Aristotle and Aquinas say? Explore the different traditions. Offer all kinds of seminars with a wide range of scholars from left, right, center. Develop their intellectual capacity, which is the capacity to be deliberative. Help them to understand labor, capitalism, the various faith traditions, strategic thinking. We offer what amount to postgraduate-level seminars in how to create effective leaders in an institutional context–not lone celebrity activists–people who build institutions that can then be networked together. …

Another example is the impressive array of liberal arts programs now being taught in prisons on a pro bono basis by professors. For instance, the Jessup Correctional Institution Scholars Program explains:

Our Program is dedicated to a simple concept: no one in society should be deprived of access to ideas. This has led all of us, through different paths, to seek opportunities to teach and learn outside the walls of the academy, built to keep people out on the basis of their social standing and financial means. And it has ultimately led us to bring intellectual discussion inside the walls of the prison, a space that too many people consider radically separate from society. We see society as a whole riddled with locked doors and those of the prison are just one more set that we hope to open.

Everyone in the program is a scholar, and we think of ourselves as on equal moral and intellectual footing – we strive to create course content as a collaboration between teachers and students, and to make classes free-ranging discussions and workshops more than lectures.

Another solution is to do the intellectual work of the university in ways that better engage laypeople. Guided in part by Albert Dzur, I argue that the way to accomplish this is not to teach graduate students and PhD researchers to be more modest and humble. That message never sticks with an ambitious group, and it’s not really the ideal, anyway. We actually need more courageous and enterprising research. Instead, we can recognize that engaging members of the public in creating and using knowledge requires highly advanced skills–it’s a form of democratic professionalism. We should teach, evaluate, and reward excellent democratic professionalism in the academy.

A third solution is for the academy to take more responsibility–at the institutional level–for communicating research and intellectual life. It used to make some sense to assume that academics conducted research and professional reporters selected and translated the most relevant findings for their readers or listeners via mass media. If that model ever worked, it doesn’t work now that 30% fewer people are employed as professional reporters. Just as institutions of higher education created public broadcasting, so they must now launch new forms of communication.

None of these three strategies will solve the underlying problem completely. The social underpinnings are problematic and require reform. Meanwhile, there are tempting political payoffs for politicians who demonize intellectual life. But these are three ways of fighting back.