Corey Robin got some nice jabs in at the current class of younger non-academic pundits a while back:

A lot of these pundits and reporters are younger, part of the Vox generation of journalism. Unlike the older generation of journalists, whose calling card was that they know how to pick up a phone and track down a lead, the signature of this younger crew is that they know their way around J-STOR.

He went on to diagnose the the current generation as ahistorical positivists who read too much economics and not enough history. I have a different explanation: bad social science journalism, a breed of the general problem of bad science journalism.

Some people–perhaps even some journalists–seem to think of explanation as a fundamentally neutral recounting of facts, not something that can have formal conditions or persuasive interests. But explanations are arguments, too. And sometimes explanations fail because the premises don’t have the right relationship to the conclusions: though no explanatory argument is valid in the logical sense, some are much stronger than others.

Very often our chosen explanations are meant to convince us of something quite apart from a causal account of how an event occurred. We don’t read the newspaper: we get our news from TED talks, op-eds, comedian newscasters, and “explainer” journalism. And in that space, explanations often follows the form, “Y is a surprising reason for X. But Y also implies that we ought to care more about Z.” In that case, the “explainer” quite often cares much more about Y and Z. X is merely a reason to climb onto their favorite hobby horse.

Much of what gets billed in headlines as an explanation of “hows” and “whys” actually fails some of the basic rules we teach in inductive logic about inference to the best explanation. As a fan of the Vox-ification of media, I need to be reminded of this myself sometimes.

Inference to the best explanation has simple rules: all things being equal, it counts in favor of an explanation that there is some new piece of evidence that could falsify it; all things being equal, it counts in favor an explanation that it can explain more than just the single set of facts we see before us. It’s also better to avoid multiplying metaphysical entities beyond need, and to preserve as many of our pre-existing beliefs as possible. What’s more, explanations should not jump to conclusions or overclaim beyond what the evidence can support.

Regressions are not Explanations

I’m all for data journalism, but I think there is a particularly dangerous version of it that equates a regression with an explanation. One kind of explanation is a causal one, and we can often test causality using concomitant variation. We can ask: if a sick person takes the drug, do they get well? Then we can add some math and ask: are they more likely to get well than a person who didn’t take the drug? That’s statistics in a very small nutshell.

But there’s a big problem in applying these case-control methods to demographic information: we often can’t vary the big social factors while holding all else equal. So we approximate. We try to use the sheer morass of human variation to uncover independent variables that predict changes. This has led to a lot of really cool math to produce real cool studies that show that some variable predicts another variable with high confidence… while only predicting a very small part of the variation. Gee whiz!

Consider a pie that has been carefully segmented into different flavors: shoefly, sweet potato, apple, cherry, blueberry, and many others the bakers have left as a surprise. What a lot of social science regressions do is try to carefully slice out one of the sections of that pie to figure out its specific flavor. As a part of their analysis, they prove that they can say with near-certitude (high confidence interval!) that they’ve gotten nearly every crumb of the Key Lime section. What does that tell us about the rest of the pie?

Well, anyone who likes pie can tell you this: gobbling the piece completely without any crumbs doesn’t mean you’ve eaten the whole pie. I talk a lot more about low R2 R-squared values in the famous study of American oligarchy here, but this is the upshot: if there’s a lot of variability in outcomes, as you would expect in a big population of wonderfully weird, defiantly diverse, and polymorphously-perverse human beings like us Americans, and you have a very strong predictor of a very small part of that variability, you do not have an explanation of the whole thing. You do not understand the whole of America! You have that very accurate predictor of the small piece, you haven’t necessarily gotten any insight into the whole population thereby. The part–which has been carefully defined by its difference from the whole–bears no necessary or predictable relation to whole.

Donald Trump: A Case Study of Stymied Explanation

Take Donald Trump’s nomination: there’s a lot to be said for his extraordinary candidacy. A man without any political experience has been nominated by one of the United States’ two major parties, on a platform that has very little clarity and against at least one dynasty candidate within his party and several other establishment favorites. How could this happen?

I don’t think I can definitively answer that question, but I think there are two major candidate explanation types:

- One kind of explanation comes from the wellspring resentments, of which we have an increasing supply. Whites are angry at their loss of prestige. Workers are angry at the support both parties give to millionaires and bankers. As we saw with the Brexit vote, these voters seem to be willing to spite themselves and destroy their own prospects if it’ll frustrate elites. And rage over growing inequality and bank bailouts might need to find some outlet, even a destructive one.

- Another kind of explanation is that as we grow wealthier, we can afford more irrationality. It’s the rich who forgo vaccines. Safe and moderate and establishment-vetted candidates are sort of like vaccinations against bad outcomes. So as we grow richer, we become more tempted to forgo them.

I believe that most of the efforts to explain Trump fall into these categories: we’re sometimes told that we can blame Trump on the current president’s competence, for instance. Or perhaps we can blame elites who failed to respond to the financial crisis with sufficient punitiveness, as Andrew Sullivan alleged.

In journalism, though, it is more common to emphasize and sub-divide the first sort of explanation: Trump is either explained by racial resentment or by economic anxiety. (Note that both are Vox links!)

White Supremacy

If your first explanation of the Trump phenomenon is “white racism,” then it’s quite likely that we’d get along well. That’s the standard answer in most of my social network. But it basically can’t be a complete explanation: the United States has been a white supremacist country since its founding. Racism is literally written into our Constitution, and certainly structures all of our major institutions. Yet Trump’s nomination represents an unprecedented event in the US, unheralded by our history. The best precedents seem to be European nationalist parties like the UK Independence Party and the French National Front, where parliamentary politics makes such a minority view easier to advance at the national level. So we need to give an account of what has changed here to make his success possible.

A story that makes a bit more sense is to call this revanchist white supremacy. Some people really are enraged that we have a Black man as president. What’s more, some people are better able to articulate their other grievances when the President is a Black man, just as when one of the candidates is a woman the sheer efficacy of misogynistic tropes in our culture makes it difficult to avoid them. (I think in particular the trust gap with Hillary Clinton is alarming; she is one of the most honest candidates ever, and seems to have a lot of difficulty dissembling even when an easy lie would benefit her. Yet out culture’s misogynistic mistrust of women pins her to some mythical deceitfulness while her husband–a perjurer!–gets a pass.)

Possibly it makes sense to say that Trump’s candidacy is better understood not as anti-Black racism, the sort that structures our country, but as anti-immigrant racism and also of Islamophobia. But it was only a decade ago that George W. Bush was insisting that we not blame Islam for terrorism. And the hatred that Trump and his supporters show for Latino immigrants is particularly notable because it’s the one thing in which establishment Republican politicians struggled to join him: they know they can’t afford to alienate Latinos. It’s the one policy plank which he has held clearly and unambiguously from the start, and it’s the most obvious contrast with his rivals.

But could it be that anti-immigrant nationalism–a kind of racism–explains Trump’s ascendancy? That, too, seems unlikely. Immigration has been on the decline for more than a decade.

If immigration peaked in 2005, then any explanation of current discomforts would require us to believe that it has taken people more than a decade to realize it was a problem. And let me be clear: there’s almost no evidence that it has been a problem in aggregate.

If immigration peaked in 2005, then any explanation of current discomforts would require us to believe that it has taken people more than a decade to realize it was a problem. And let me be clear: there’s almost no evidence that it has been a problem in aggregate.

But it has been a problem for the segment of the population who are also voting for Trump. The anti-imigration story is usually associated with the effect that low-skill immigrants have on the labor market participation of low-skill American workers. So anti-immigrant attitudes can understood as partly an economic concern, and these could partly motivate Trump’s supporters.

The Trumpenproletariat

Since I’ve been writing about superfluousness lately, you will not be surprised to hear that I worry that there is a superfluousness explanation available here. Low-skill immigrants put particular pressure on the low skill workers who are only marginally attached to the workforce. So it is reasonable for them to fear that they will be undercut by undocumented workers who can undercut their wage requirements. But there’s an inconvenient fact that this explanation must negotiate: Trump’s supporters have a much higher average household income than most Americans, and certainly higher than any of the Democratic candidates. The median Republican primary voter who picked Trump reported a household income of $72,000 per year. (The median American household income is $56,000.)

With such a high income, it seems unlikely that his support is primarily drawn from within the lumpen proletariat, that counter-revolutionary group that Marx described in The 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon:

Alongside decayed roués with dubious means of subsistence and of dubious origin, alongside ruined and adventurous offshoots of the bourgeoisie, were vagabonds, discharged soldiers, discharged jailbirds, escaped galley slaves, swindlers, mountebanks, lazzaroni, pickpockets, tricksters, gamblers, maquereaux [pimps], brothel keepers, porters, literati, organ grinders, ragpickers, knife grinders, tinkers, beggars—in short, the whole indefinite, disintegrated mass, thrown hither and thither, which the French call la bohème.

That’s not Trump’s supporters. If income is any guide to one’s role in the economy, then his voters are significantly less “superfluous” than either Clinton’s or Sanders’ supporters. But this is comparing apples and oranges. How can we understand this income gap?

- Trump’s supporters are, first, voters. Poor people don’t vote in the same numbers as the middle-class and rich, so we should expect (and find) that voters have higher median household incomes than non-voters.

- Trump’s supporters are Republicans. And Republican voters just are richer than Democratic voters. Trump’s supporters are still the poorest of the bunch: Cruz’s voters were about the same, while both Kasich and Rubio had median household incomes more than $10,000 higher. (Kasich’s supporters had a median of $91k; Rubio’s supporters had a median of $88k.) But we have to be careful here: Republicans are richer because they are whiter and older than Democrats.

- Trump’s supporters tend not to have college degrees. Thus even if they are currently employed, they’re experiencing a decline in their prospects under our new credential economy.

- Trump’s supporters come from poor places where the lifespan is decreasing. I still think this is the single best explanation of this pie-slicing sort: lifespans decreased for a certain population in the first time in modern history, and at roughly the same time, those groups chose a surprising candidate.

That’s why I associate Trump with the superfluous ones. Yet it’s important to recognize that his supporters are experiencing relative and not absolute impoverishment: they are worse off than they were, but not worse of than the Muslims, immigrants, and African-Americans they seem to despise. That loss of status may be a better indicator of how surpluses turn into superfluousness than any other; immigrants aren’t at all useless, they’re too busy being exploited! Thus racism still is a very relevant part of the story.

Against Epistocracy

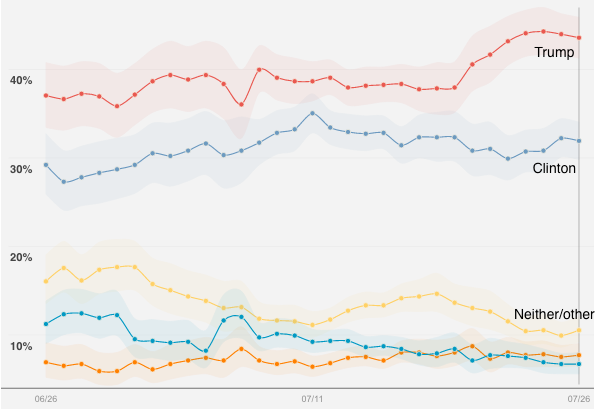

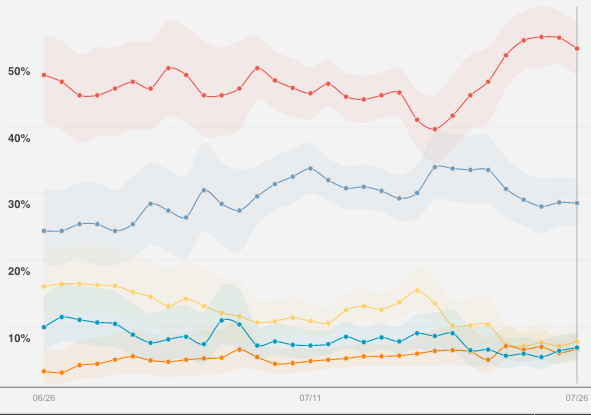

It’s notable how uniform the establishment reaction to Trump has been: ordinarily measured newspapers and even conservative magazines have lined up against him in large numbers. Pundits and wonks see him as a threat to democracy and the rule of law, which is highly inflated rhetoric infrequently applied to major party presidential candidates. So how could he have won his party’s nomination, and seem to have such a good chance of winning the presidency? (Though perhaps not SO good a chance?)

It may seem that Trump’s apocalyptic rhetoric has forced the chattering class to respond in kind. But in fact, elites have been speaking in apocalyptic terms for a while now. My readers are mostly academics, so they will be able to immediately recall the long list of threats to democracy: wealth inequality, the failure of campaign finance reform, the growth of long-term unemployment, the coming entitlements crisis, mass incarceration, police brutality, de-industrialization, racism, multiculturalism, presidential overreach, climate change, epistocracy, automation, etc. Perhaps one or a few of these threats did fundamentally break democracy?

Or perhaps it’s the establishment itself that has become too uniform, that has begun to substitute both its factual and moral judgment for an honest consultation of the will of the people. As a member of that credentialied elite, I’m generally sympathetic to this. But the major problem with the rule of credentialed elites is three-fold:

- Even those who tend to get the right answer may still be wrong, but overconfident errors tend to be more costly.

- Experts have a tendency to speak beyond their legitimate expertise.

- Experts can self-deal in ways that are difficult for non-experts to detect, and indeed they have managed to claw back most of the shared gains from their expertise.

An additional problem might be that the rule of expertise is only considered legitimate insofar as it doesn’t lead to undemocratic control of policy. By creating invidious comparisons among citizens, elite rule creates a class of superfluous men and women who must live with the constant reference to our democratic culture while recognizing that they are excluded from it. They are thus living their lives at the point of conflict between principle and practice, the contradiction between rhetoric and lived experience, much like African-Americans in the US, who must constantly hear our lip service about racial equality in its practical absence.

We live in a time of self-government limited by many forces, but the most relevant force most Americans experience is the way that their projects and desires are hamstrung by wonks and nerds. It’s not usually the very wealthy who tell us what to do. It’s usually an upper-middle-class professional: a lawyer, a doctor, perhaps an engineer or a psychologist.

In almost every case, it was ultimately a college-certified teacher or professor who put and end to a person’s dreams and alienated them from credentialed elites; if that didn’t happen–as it is unlikely to have permanently done for any of my readers–then you’re more likely to find yourself within the top thirty or forty percent of incomes and influence. Teachers put up walls to success in our economy.

The White Working Class

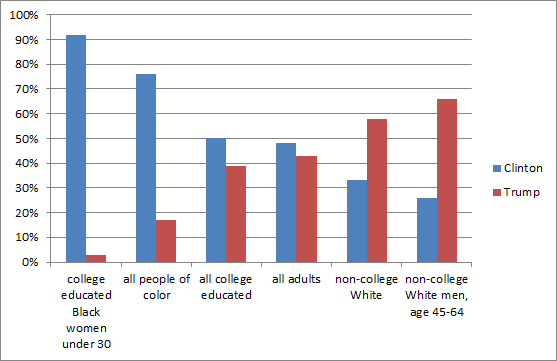

My friend Peter Levine argues that the data supports the supposition that low social class explains Trump support. One odd thing about this finding is that it requires us to divvy up the working class into whites and non-whites. Having done this, we then find that non-white working class members strongly support Hillary Clinton, and white working class members strongly support Donald Trump. Thus something called “social class” predicts candidate support!

I have ample evidence that Peter is smarter than me. But I just don’t see how he has come to this conclusion. It seems to me that he is saying that white supremacy cannot be an explanation, because poor white people support Trump and poor Black people don’t. Yet Peter is well-aware that one of the key components of white supremacy is the weaponization of the poor, the idea that preserving the social privileges of whiteness can allow elites to prevent working class consolidation.

So I have to ask: in this conception of social class, is it the “social” or the “class” doing the work? I understand the strategic point Levine is making, that the best response to superfluousness is organization, and this even applies to poor whites tempted by white supremacy. I am sympathetic to that point even though I’ve argued that:

we should not hope for 100% political participation, at least insofar as that requires that white supremacists and chauvinists find viable politicians who will court them openly.

Probably we can and will come to rapprochement on the strategic issue, since there are alternate, non-supremacist ways for those groups to organize. But it seems to me that his enthusiasm for participation has led him into an analytic error. Give that he is much smarter than me, I’m sure I’ll turn out to be wrong about this… but I must wait to hear the correction before I’m convinced.

The Null Hypothesis: Incompetence and Fear

In explanations, it’s important to give the null hypothesis its due. Sometimes no particular thing had a strong effect on an outcome: sometimes the best explanation is chance, bad luck, or incompetence. And I think all three play a role in Trump’s rise. In particular, the Republican Party failed to seize on a “better” candidate during the crucial early states because too many of them were pledged to Jeb Bush. Long after Bush ceased to be viable, they couldn’t coordinate around an alternative for fear of offending his family. And with so many candidates, and no room for backroom deals, elections become chaotic; they fail to choose the person that most people would prefer (the Condorcet winner).

Yet I have come to believe that the best guide to his rapid ascendance is not some statistic but what he says. To me he looks overwrought, bombastic, and silly. Yet he regularly draws larger crowds than my lectures, so maybe he’s on to something. Why is this rhetoric so effective?

One thing that unifies much of the the US is the sense that there are major threats left unaddressed. We see constant reports of terrorist attacks, police shootings, and mass shootings that target both civilians and law enforcement. We live in a time of unprecedentedly low crime, and yet the news seems to be full of criminal atrocities. No institution feels legitimate any longer; we have one of the most upstanding presidents in modern history, and yet he is regularly de-legitimized in the rhetoric of both the left and the right. (And I too can think of dozens of reasons but the criticisms have grown faster than the reasons.)

So my suspicion is that the best explanation of Trump is simply that he is able to mobilize our fears–well “our” fears–not mine, but the ones that trouble our culture. It remains to be seen whether “our” fears are truly irrational; I think that they are. But we should think of Trump as running to be the Commander-in-Chief for the ongoing Global War on Terror.

If this is right, describing Trump as racist is irrelevant. His primary appeal is as a strongman, a defender against terror; racism is irrelevant except insofar as it helps to identify the source of the threats against which he’ll defend us. His strongman appeal is bolstered by its disconnection to any actual strength. It almost seems to be helped by its association with with his remarkably fragile ego.

Now, here’s the thing: citing terrorism as the main explanation for such a complicated rise is indeed a “surprising explanation” of the sort I warned against above. I am coming very close to reiterating a debunked theory of Trump, that his supporters are more “authoritarian” than other voters. The counter-narrative is that Trump’s supporters are… nationalist populists, proud to be American and cynical about elites. But in this excellent recent piece, James Kwak captured part of the problem with this sort of analysis:

Racism isn’t a virus that falls out of the sky. It’s the product of historical contexts. I can’t prove that today’s heightened racism results from the Great Recession, although it seems perfectly plausible to me. But by the same token, saying “It’s racism!” doesn’t preclude the role of economic factors in making that racism attractive.

Similarly, mistaken feelings of poverty and vulnerability (among a relatively stable and wealthy group) isn’t a virus that falls out of the sky: it doesn’t preclude the possibility that nationalism and the hatred of the currently non-white and likely forthcoming non-male President-as-elite-representative cause those feelings of nationalism–racism by another name–and and misogyny–which is what hatred of elites looks like when it’s at home.

So I suspect that it helps to spell out a useful understanding of Trump’s appeal, not at the margins but for the mass: they are actually quite safe, and yet they don’t feel safe: they feel vulnerable, fragile, and in need of protection. This makes him a great candidate to run against a hawkish Secretary of State–because she is a woman and cannot so easily play “strong man” in our subconscious.

If immigration peaked in 2005, then any explanation of current discomforts would require us to believe that it has taken people more than a decade to realize it was a problem. And let me be clear: there’s almost no evidence that it has been a problem in aggregate.

If immigration peaked in 2005, then any explanation of current discomforts would require us to believe that it has taken people more than a decade to realize it was a problem. And let me be clear: there’s almost no evidence that it has been a problem in aggregate.

This is part of the library of Albert Shanker (1928-77), which lines the walls of the conference room of the Albert Shanker Institute, which is inside the American Federation of Teachers’ Building in Washington. I was there earlier today. It seems fitting that such a library should rest in the heart of the AFT, exemplifying the long, rich, and living tradition of intellectual life within the labor movement (and—importantly—outside of universities).

This is part of the library of Albert Shanker (1928-77), which lines the walls of the conference room of the Albert Shanker Institute, which is inside the American Federation of Teachers’ Building in Washington. I was there earlier today. It seems fitting that such a library should rest in the heart of the AFT, exemplifying the long, rich, and living tradition of intellectual life within the labor movement (and—importantly—outside of universities).