According to the “interactionist” theory of Mercier & Sperber 2017 (which I discussed on Monday), human beings evolved to make smart decisions in groups, and that requires us to exchange reasons. We naturally want to express reasons for our intuitions and critically assess other people’s reasons for their beliefs. It matters how well we perform these two tasks.

One familiar kind of person frustrates discussion by constantly linking every belief that he endorses back to one foundational principle, whether it is a constitutional right to individual freedom, God’s will, or equality for all. The problem is not the core belief itself but the way his whole network of beliefs is structured; it prevents reasoning around his core idea if you don’t happen to share it.

A different familiar figure is the person who offers many ideas but cannot provide a reason for most of them. If we think of a reason as a link between two ideas, then this person’s network has no links. Whereas the first network was too centralized, the second is too disconnected.

We don’t literally possess networks of beliefs; rather, a network graph is a way of representing our reasoning. I conjecture that the formal features of such a network can predict whether the person will deliberate well. To illustrate (but not to prove) that conjecture, I will discuss two Kansas State students who participated in an online discussion as part of the research that led to Levine, Eagan & Shaffer 2022.

Before discussing how socioeconomic factors affect health, all the students in this study wrote short passages describing their personal views. Adèle and Beth are pseudonyms for white undergraduate KSU women, aged 21 and 22, whose mothers had not attended college.

Adèle wrote:

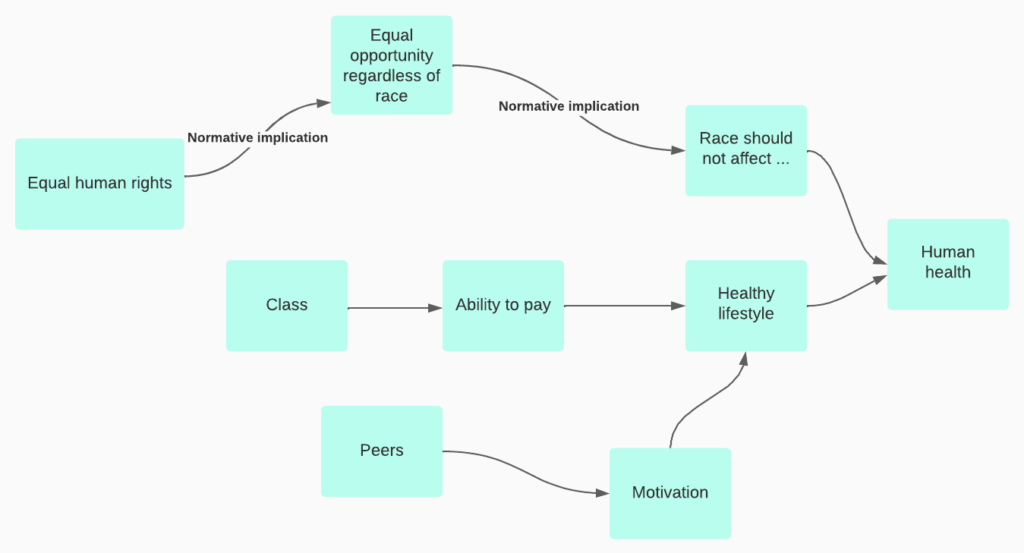

In my opinion, race should not influence the human health and well-being because every person should have an opportunity to succeed no matter what race they are. Social class influences the health because a healthy lifestyle is more expensive, but also a healthy lifestyle means physical activity and that does not depend on the social class, it depends on individual motivation. A social factor would be the people that we surround ourselves with. If we interact with people that live a healthy lifestyle, we can get influenced and borrow some of their habits. But is also true that for the lower class is the hardest to live a healthy lifestyle because they cannot afford one.

I think we could informally diagram her view with the graph below. The nodes are her stated beliefs. The arrows are her causal claims, except where I’ve denoted them as normative implications. This graph does not explain why Adèle formed her intuitions (i.e., why these beliefs formed in her mind) but rather represents the explicit reasons that she offers to explain her beliefs to others.

Beth wrote:

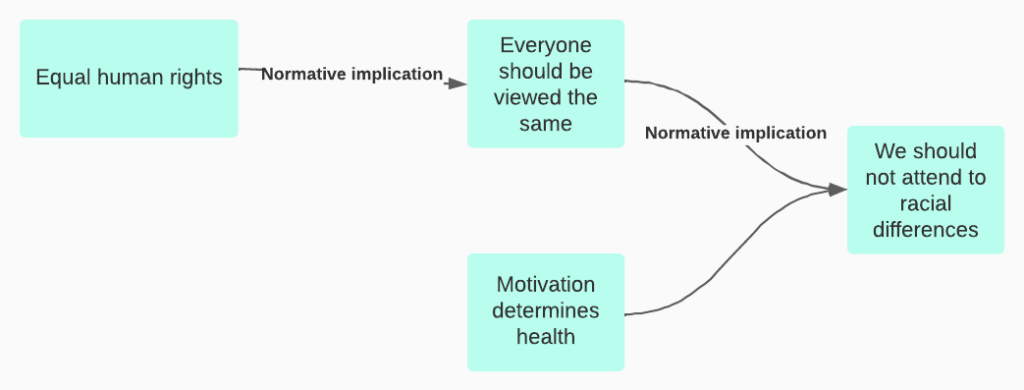

My thoughts on the impact of race, class and social factors on determinants on human health and wellbeing are that no matter what your race or social class is, you should be treated equally because the color of a person’s skin should not affect the way you view them. Both a black and white person can put in the same amount of hard work and effort to be able to reap the benefits of a happy healthy life. However, with that being said, there are some people who do not work as hard and that puts them in a lower social class than others. possibly making their overall health and wellbeing less than someone who is up in a higher social class.

I think we could informally diagram Beth’s view like this:

I propose that Adèle will be a better conversation-partner than Beth, not because her beliefs are superior but because of the structures represented by these two graphs.

Adèle has generated several independent intuitions (moral and empirical) that push in somewhat different directions. They are all connected to the idea of health, because that is the assigned topic, but there is some wiggle room between her beliefs, and she has identified several causes of the same outcomes. Adèle and I could talk about several of her intuitions. I could ask her to offer reasons for each one, and we could turn to another issue if we found that we disagreed on that point.

Meanwhile, Beth only offers reasons for one conclusion: that people should not pay attention to racial differences. I would worry that we couldn’t engage once she had made that point. Her sentence that begins, “However, with that being said,” does not actually present a conflicting point but elaborates on her main argument.

When asked whether “Everyday people from different parties can have civil, respectful conversations about politics,” Adèle agreed, but Beth strongly disagreed. Adèle also rated the online discussion more highly than Beth did as a learning experience. This is suggestive evidence that Adèle was more deliberative (in this context) than Beth.

Beth did participate in the online discussion four times and explicitly referred to previous commenters with openings that look civil, such as: “Although I agree with everything you have said, I think. …” However, all four of her contributions were variations on her basic point that success is due to hard work.

In contrast, when Adèle saw a post in the online discussion that recounted a story about a white woman who had succeeded in life due to her own hard work, she responded deliberatively, trying to connect to the previous writer’s ideas. She began: “I saw you talked about how hard work and effort can help you achieve a better lifestyle and I agree with it.” She had expressed this belief in her personal statement prior to the discussion, and it is represented in the first graph above.

She added, “But we also need to have in mind the people that grow up in less fortunate families and have different aspirations that some people have.” Here she introduced another belief that she had already held. She supported it with reasons: “For some of us, going to college is a thing that we knew it’s going to happen in our lives and we never question if we might go or no. But for some people they do not have this opportunity to afford college. … I believe that some people even if they are willing to put hard work and effort, not all of them are guaranteed to succeed.” She then acknowledged a criticism and addressed it: “Of course, there are people who succeeded but I believe that there are a lot of them who did not. And for a person who is less fortunate is not too easy to live a healthy lifestyle.”

My claim is not that Adèle formed better beliefs by reasoning. She may have developed her beliefs intuitively, as we generally do. Nor is there evidence that she revised her beliefs in response to objections, any more than Beth did. My claim is that Adèle contributed better to the group’s discussion because the structure of her reasons permitted more interaction.

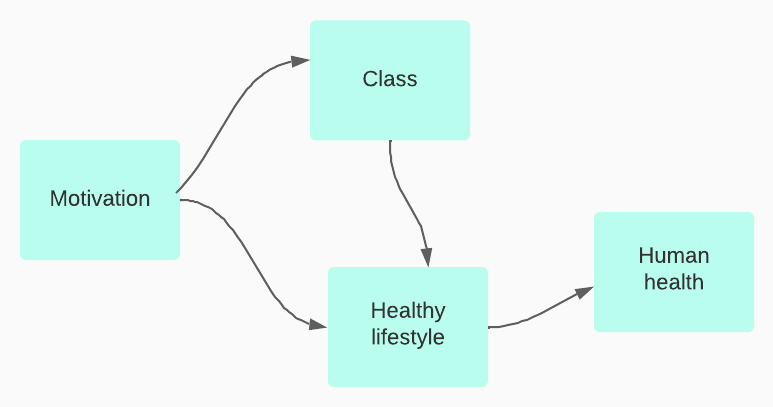

(Two limitations of this post: First, I chose the examples to illustrate my main point. That does not prove the general pattern. Second, my diagrams could be biased. For instance, Beth’s belief that “motivation determines health,” which I depicted above as one node in her network, could be unpacked to look like this:

Adding those four nodes to her map would make her whole graph look almost as complex as Adèle’s. I am still looking for less subjective approaches to mapping text. In a lot of my current work, I elicit network structures by asking people multiple-choice questions, rather than graphing their open-ended statements, because the quantitative data seems more reliable for making interpersonal comparisons.)

Sources: Mercier, Hugo and Dan Sperber, The Enigma of Reason, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 2017; Levine, Peter & Eagan, Brendan & Shaffer, David. (2022). Deliberation as an Epistemic Network: A Method for Analyzing Discussion. 10.1007/978-3-030-93859-8_2. See also modeling a political discussion; individuals in cultures: the concept of an idiodictuon; and how intuitions relate to reasons: a social approach.