The 34-page article, Deliberative Technology: A Holistic Lens for Interpreting Resources and Dynamics in Deliberation (2017), was written by Jodi Sandfort and Kathryn Quick, and published in the Journal of Public Deliberation: Vol. 13: Iss. 1. In the article, the authors “introduce the concept of deliberative technology as an integrative framework to encapsulate how facilitators and participants bring different resources into use in deliberative processes.” Read an excerpt of the article below and find the PDF available for download on the Journal of Public Deliberation site here.

From the introduction…

Public deliberative processes can create many positive results, including enabling participants to understand substantive issues, appreciate other perspectives, and build their abilities to develop or act upon solutions (Gutmann & Thompson, 2004; Jacobs et al., 2009; Mansbridge, 1999). To readers of this journal, this almost goes without saying. Yet, attempts to create these results often fail (Fung, 2006; Nabatchi et al., 2012; Quick & Feldman, 2011). No single dimension explains success or failure; the results of deliberation arise through a complex mixing of contextual and design features. However, as deliberation becomes an increasingly expected mode of governance (Leighninger, 2006), there is a thirst for more practical guidance about how to make deliberation efforts more successful.

Seasoned practitioners have a healthy skepticism of how-to guides. They know there is no “master recipe” or set of rules that will reliably produce successful public deliberation. Instead, they are aware that a variety of deliberative techniques exist to serve particular purposes (Creighton, 2005; Kaner, 2007; Leighninger, 2006), and are able to draw nimbly on a wide palette of them to design each deliberation to suit particular purposes (Bryson et al., 2013; Carson & Hartz-Karp 2005). Indeed, as skilled practitioners think through how to accomplish the goals of deliberation, they may experience a diminishing return on investment for advanced planning in deliberation. Many find the unpredictability of deliberative processes not only inevitable, but also inherently desirable. As they gain more experience and judgment, they actively read, respond to, and shape emergent dynamics in deliberation to steward productive deliberation. Thus, a variety of modes of engagement emerge from the interactions among 1) the nature of the problem to be worked on; 2) the policy imperatives about participation (LeRoux, 2009); and the combination of the facilitator’s skills and preferences with available resources (Davies & Chandler, 2012).

This article complements what seasoned practitioners already know by introducing the concept of deliberative technology to encapsulate how facilitators and participants bring different deliberative resources into use in particular settings in the design and enactment of deliberation. Developed from inductive theory building from ethnographic research on three deliberative processes, the deliberative technology concept provides a means for clearer understanding about the unpredictable dynamics of deliberation. The cases were selected from a unique field research setting in which hundreds of facilitators were trained in a particular deliberative approach (Quick & Sandfort, 2014). The projects illustrate differences in the implementation despite the fact that all three involve a common aim, a single geographic region, and the same set of deliberation techniques. In this paper, we use deliberative technology to describe the general concept and deliberative technologies (plural) to describe and draw attention to the multiple ways in which deliberative technology takes form in particular contexts.

After elaborating the concept of deliberative technology, we present data on how deliberative technologies emerged during the three projects and how participants experienced them. We emphasize the divergences in the experiences of the three processes, even where comparable techniques or concepts or physical materials were used, to make sense of how deliberative technology emerges in practice. We conclude the paper by exploring the implications, for both training and practice, of the new understandings afforded through the deliberative technology concept. In our own experience – as people who are simultaneously practitioners, teachers, and scholars of deliberation – understanding deliberative technology helps people to proactively design and adaptively manage deliberative processes.

Download the full article from the Journal of Public Deliberation here.

About the Journal of Public Deliberation![]()

Spearheaded by the Deliberative Democracy Consortium in collaboration with the International Association of Public Participation, the principal objective of Journal of Public Deliberation (JPD) is to synthesize the research, opinion, projects, experiments and experiences of academics and practitioners in the emerging multi-disciplinary field and political movement called by some “deliberative democracy.” By doing this, we hope to help improve future research endeavors in this field and aid in the transformation of modern representative democracy into a more citizen friendly form.

Follow the Deliberative Democracy Consortium on Twitter: @delibdem

Follow the International Association of Public Participation [US] on Twitter: @IAP2USA

Resource Link: www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd/vol13/iss1/art7/

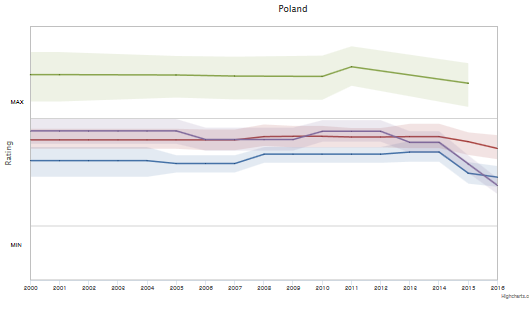

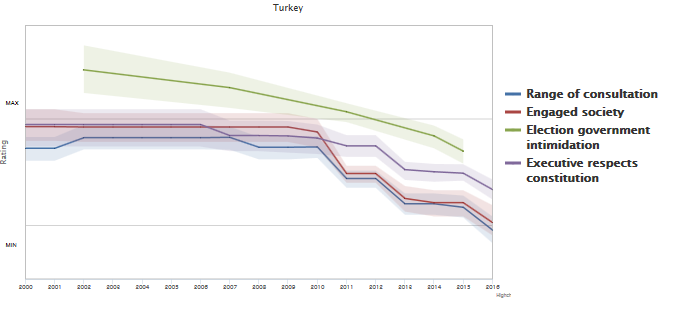

The pattern is less pronounced but similar in Poland since 2011.

The pattern is less pronounced but similar in Poland since 2011.