I have all kinds of (unoriginal) doubts about the new venture called University of Austin. The promise to create a novel financial model sounds empty until they actually describe it. (Since more than 3,500 US colleges and universities compete today, I would guess that great ideas for saving money have already been tried.) At least in Bari Weiss’ version, the case for a new university rests on a damning portrait of the existing ones that doesn’t match what I observe. And, as someone who values freedom of expression and robust debate, I don’t see a serious effort to grapple with the challenges to freedom, such as directives by donors and foundations, state regulations, the decline of tenure, and shrinking liberal arts enrollments. (Liberal arts courses are the most natural homes of vibrant debate.)

On the other hand, there is nothing more traditional than a group of Americans issuing a jeremiad against their doomed and corrupt society and founding a new college as a solution. That describes Calvinist pilgrims, Jeffersonian democrats, Catholic immigrants, Midwestern progressives, formerly enslaved people, Mormons in Utah, boosters of new Western states, sixties idealists, fundamentalist revivalists, and more.

If anything, it is disappointing that the rate of founding new colleges and universities has slowed so much. Many of the new ones appear to be conventional branch-campuses of existing state systems–important for meeting demand but not necessarily innovations.

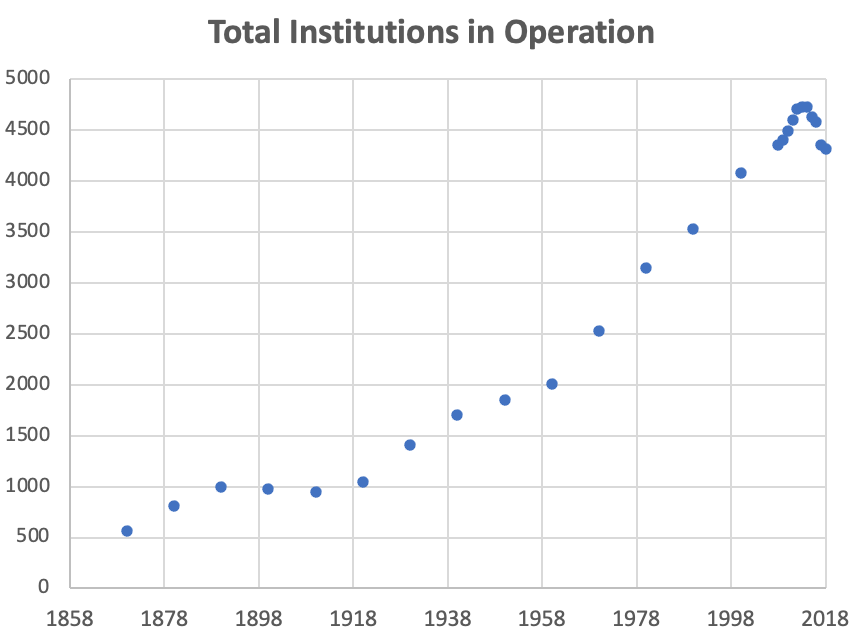

Fig 1, shows that the total number of colleges and universities rose rapidly from 1918 to 1998 but peaked around 2013 and has fallen since.

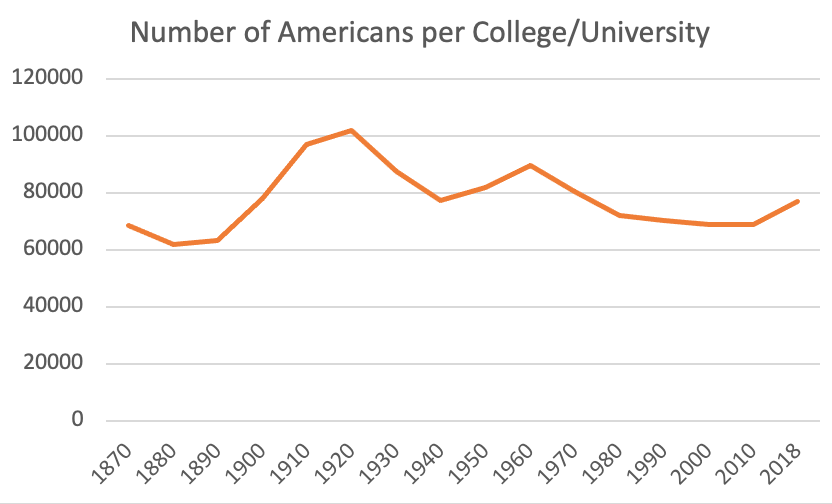

That graph does not adjust for population growth. If we value choice and innovation, we might like to see more colleges and universities per capita, which would mean fewer people per existing colleges (shown in my second graph).

The nineteenth century actually exhibited a worsening of this measure, because population growth outpaced even the rapid formation of new institutions. Much of the 20th century saw improvement, although the number of new institutions could not quite keep up with the Baby Boom in the 1960s. Of late, we have seen more people per college.

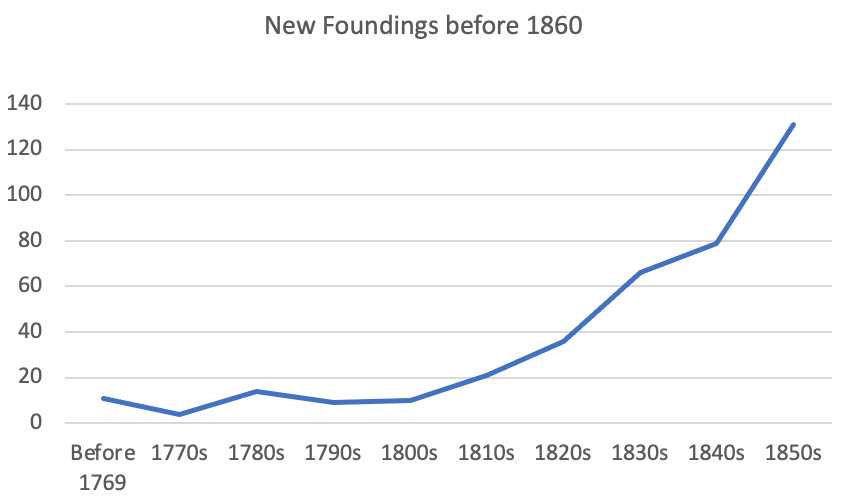

The total number of colleges and universities that are open in a given year doesn’t quite indicate the rate of foundings, because older institutions go out of business. Tewksbury (1932) estimated that four out of five antebellum colleges failed. I can’t find continuous data on new foundings for US history as a whole, but the third graph indicates a rapid increase in that measure from 1820-1860.

I would place University of Austin in that tradition. I am not enthusiastic about their diagnosis or plan, but I think it’s appropriate for disaffected people to start new institutions so that we (and they) can find out what their ideas would really mean in practice. That is how we got the array of colleges and universities that we see today, from Oberlin College to Liberty University, from UCF (with 66k students) to Deep Springs College (with fewer than 30), from Notre Dame to Naropa University in Boulder, CO. I’ve mentioned some outliers, but the overall trend is increasing similarity or “institutional isomorphism.” I’m for innovations that mix things up.

See also: the Harper’s letter is fatally vague; the ROI for philosophy; rationales for private research universities; the weirdness of the higher ed marketplace; what kind of a good is education?; a way forward for high culture etc.