Populism and Higher Education for the Age of the Smart Machine

Real populism does not mean simply railing against banks, as liberals pining for an Elizabeth Warren presidential bid assume. Genuine populism is a vision of democratic renaissance based on cross-partisan civic empowerment. It addresses the challenges of concentrated power specific to each age.

We need populism for the age of the smart machine. People's capacities for self-directed effort are eroded not only by concentrated economic power and economic inequality but also by what the South African intellectual Xolela Mangcu calls "technocratic creep." Technocratic creep erodes both individual agency and also the independent centers of popular power, self-organization, and civic learning which are the foundation for broad, democratizing movements.

For such populism, higher education is a crucial site for making change.

In periods of populist upsurge, people empower themselves -- they are not empowered by politicians or government. But political leaders and government policies play crucial partnering and context-setting roles.

There is a rich tradition in this vein, as diverse as the 1862 legislation which established land grant colleges, "people's colleges" and "democracy colleges," Franklin Roosevelt's Wagner Act which sped the growth of unions in the 1930s, "maximum feasible participation" provisions of Lyndon Johnson's War on Poverty and the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act which facilitated community organizations, and civic environmental initiatives of the Clinton years. Civic environmentalism shifts from top-down regulation to the setting of broad goals on air quality and other measures and providing resources for communities to work out strategies themselves.

Revival of such democratizing politics is now visible in cities. As Harold Myerson described in "Revolt of the Cities," a new group of progressive populist mayors in New York, Pittsburg, Boston, Minneapolis, Santa Fe and elsewhere are addressing problems of growing inequality while championing measures which facilitate worker and community self-organization. Benjamin Barber, in his recent book, If Mayors Ruled the World, shows that the movement of cities as "laboratories for democracy" is global. Such examples of government as empowering partner are important to build on.

We also need populist politics that reverses technocratic creep.

In the United States, a civic infrastructure of mediating institutions of many kinds -- parties, unions, locally rooted businesses, schools, congregations, colleges, ethnic groups, libraries, settlements, county extension offices, and others -- once connected people's lives with the larger world. Despite prejudices and parochialism, they also often had public qualities which created what Sara Evans and I have called free spaces, spaces for self-organizing, democratic intellectual life, and development of political capacities for work across partisan and other differences, to address problems and negotiate a common way of life. These were the foundations for movements such as civil rights, the women's movement, labor organizing, and farmers cooperatives, changing the whole society in periods like the New Deal and the 1960s.

Free spaces and mediating institutions were also under threat. As early as 1902 the visionary settlement house leader in Chicago, Jane Addams issued a prophetic warning. In Democracy and Social Ethics, she contrasted the corrupt ward bosses in the Chicago political machine whom she long battled with "the reformer who believes that the people must be made over by 'good citizens' and governed by 'experts'?" Because they were involved in the life of the people, ward bosses, "at least are engaged in that great moral effort of getting the mass to express itself, and of adding this energy and wisdom to the community as a whole."

Over the 20th century, higher education fed the growth of expert power and eroding popular power through the spread of a theory of knowledge, positivism, which holds that outside, "objective" experts are the only source of sound knowledge. Faculty research cultures became increasingly detached from interaction with problems of communities and democracy, as shown in American Academic Cultures in Transformation, edited by Thomas Bender and Carl Schorske. Professionals were socialized as "disciplinary" experts, in the phrase of Bender, losing the "civic professional" identities which had rooted their work in local civic life.

Such developments in higher education contributed to transformation of mediating institutions into service operations where lay citizens are redefined as needy clients and customers.

This dynamic threatens to intensify in the age of the smart machine, as conservative New York Times columnist David Brooks describes ("Our Machine Masters," October 30, 2014). Artificial intelligence means that "Engineers at a few gigantic companies will have vast-though-hidden power to shape how data are collected and framed, to harvest huge amounts of information, to build the frameworks through which the rest of us make decisions and to steer our choices."

Progressives need to take learn from these insights and deepen their democratic strategies.

Higher education, contributing to technocratic creep, will be central to democratic change. Colleges and universities are upstream settings which shape the identities, practices, and frameworks of leaders across the whole of contemporary societies. They sustain values and practices such as independent inquiry, free exchange of ideas, the importance of evidence, and the commonwealth of knowledge which are indispensable counterweights to domination by outside experts. And they have a rich narrative of "democracy's education" which shows signs of revival.

This democracy story is evident in the forthcoming collection, Democracy's Education. In the book, Martha Kanter, undersecretary of education for higher education in the first years of the Obama administration, outlines government policies which she helped to create in the tradition of government as empowering partner, facilitating revitalization of civic learning and democratic engagement in higher education.

The democratic narrative is visible in a new national conversation called "The Changing World of Work -- What Should We Ask of Higher Education?" aimed at bringing the larger citizenry into decisions about the economy and work we need, to be launched at the National Press Club, January 21, sponsored by the Kettering Foundation, the National Issues Forums, Augsburg College, Campus Compact, American Democracy Project, Imagining America,-the-American-Library-Association's-Center-for-Civic-Life and others.

Finally, the democracy story of higher education is evident in civic science, a framework for understanding science in society which emphasizes science as a set of democratic practices contributing to human empowerment and scientists as citizens who develop the political skills of work with their fellow citizens to negotiate a shared way of life.

All are resources for democratizing politics in the age of the smart machine.

Harry Boyte edits Democracy's Education, forthcoming from Vanderbilt University Press February 1st.

$100 or 100 Friends

This morning, someone on my Facebook feed posed a tantalizing question – Would you rather have $100 or 100 friends?

The question seemed particularly timely since just last night I had a (pleasant) argument with a certain street canvasser who seemed convinced I wasn’t doing my part philanthropically.

Ever since my illustrious 2-day stint working for MassPirg, I’ve made a point of being friendly to street canvassers, but I rarely, if ever, donate that way since I find it an inefficient fundraising tool with questionable labor practices.

Usually my conversations simply entail a quick, polite exchange, but the gentleman last night was particularly persistent. He started with a soft sell of small talk, then asked that I at least hear him out before repeatedly refusing my rebuffs.

Don’t get me wrong, it was a pleasant conversation – even if it was 15 degrees out I could talk all day about the philosophy of philanthropy. But I was fairly certain I was wasting his time.

When I first declined, saying that I had other philanthropic obligations, he said:

Let me ask you this – if you had more money would you give to more things?

That seemed an odd question. I paused.

No, no no, he corrected, if you had all the money would you give to all the things?

Probably not all the things, I told him. Before he could clarify what he meant by “all” I explained my hesitation –

If I had more money, I think, it would be a question of whether its better to give to more things or to give more to the same things. Since I don’t have more money, I told him, I hadn’t given that question sufficient thought.

He was nonplussed.

He wanted me to commit to giving $1 a day to his organization. Is there anything in your life, he asked, that you wouldn’t be able to do if you gave $7 a week more?

Well….yes, I told him.

He didn’t believe me.

Now it’s perfectly fair to question whether I do enough philanthropically. I probably don’t. And I probably should do more.

Can I give $7 a week more? That’s a really good question and one I should ask myself constantly. One I should push myself on. I don’t honestly know the answer, and I’m probably won’t be able to determine the answer standing on a street corner talking to a stranger.

But it’s a good question to think about.

And now I come back to the original question – Would you rather have $100 or 100 friends?

I guess the truth is $100 doesn’t go that far. Whether you spend it on yourself or give it away, unless you’re in need of the food or shelter $100 could help provide, it doesn’t really provide much value.

$100 or 100 friends?

I think I’d rather have 100 conversations with strangers.

NIF Hosts Live Conversation on Higher Ed & Work, Jan. 21

We want to encourage you to watch the live broadcast of a key conversation event that the National Issues Forums Institute & the Kettering Foundation – both NCDD organizational members – are hosting on Jan. 21st on the role of higher education in our country and in the economy. You can learn more below or read the original NIF announcement here.

Join us for a national conversation on The Changing World of Work: What Should We Ask of Higher Education?

On Wednesday, January 21, 2015, from 9 am-noon, the National Issues Forums Institute will stream the event live from the National Press Club on the all-new nifi.org.

On Wednesday, January 21, 2015, from 9 am-noon, the National Issues Forums Institute will stream the event live from the National Press Club on the all-new nifi.org.

Speakers and panelists include:

- Jamie Studley, Deputy Under Secretary of Education

- Nancy Cantor, Chancellor, Rutgers University-Newark

- David Mathews, President, Kettering Foundation

- Harry Boyte, Senior Scholar in Public Philosophy, Augsburg College

- William Muse, President, National Issues Forums Institute

- Other distinguished leaders from policymaking institutions, business, and civic and community groups

Organized by the National Issues Forums Institute, the American Commonwealth Partnership at Augsburg College, and the Kettering Foundation, this conversation responds to concerns voiced by thousands of citizens in more than 160 local forums in which participants deliberated on the future of higher education. Cosponsoring organizations include the American Association of State Colleges and Universities, the American Democracy Project, Campus Compact, Imagining America, and others.

What kind of economy do we want? Given momentous changes in the economy and the workplace, what should we expect of American higher education? Do our colleges and universities bear some responsibility for the challenges facing young graduates today? Do they owe it to society to train a new generation of entrepreneurs, innovators, job creators, and citizen leaders? And do we still look to them to be the engines of social progress and economic development they have been in the past? During this event, new resources will be released meant to spark local conversations on these and other questions.

Check back here for updates and on the day of the event to view the stream.

You can see the original version of this NIF post at www.nifi.org/en/groups/stream-changing-world-work.

on the radio, talking about civic education

On January 6, I joined the inimitable Arnie Arnesen on her New Hampshire-based Pacifica Radio show to discuss civic education. She thinks efforts to repress political participation are responsible for the marginal place of civics in our schools. The audio is here; my segment starts at about 27:45 and goes to the end.

The post on the radio, talking about civic education appeared first on Peter Levine.

Introductions (Editor’s Introduction from 23.2)

It is customary for a new editor to say a little about himself and how he plans to tackle the goals of the journal. But in the spirit of co-creation, I’d like to start this issue by extending special gratitude to the longest-running member of the editorial staff: Habib Gharib. Gharib has worked on the journal since 2001, and his attention to both grammar and content is impeccable. He has at various times been listed on our masthead as “Assistant Editor” and “Assistant Managing Editor,” but whatever the title he has edited patiently and with great skill. We are grateful for his services.

Steve Elkin has often said something like what he wrote in his last book: that political science needs to be either reinvented or reworked so that “efforts at explanation and evaluation are tied to the question of good political regimes and how they may be secured and maintained.”[i] This reworking has been the business of The Good Society since Elkin founded the Committee on the Political Economy of the Good Society with Soltan and Gar Alperovitiz and started printing a newsletter in 1991.

Since that time, the journal has had a certain thematic unity: the articles we have published have focused on matters of institutional design, democratic deliberation, the history of political theory, and, perhaps obviously, political economy. But the real unity of the journal has been methodological, an intensive focus on this holistic and normative approach to political science. In his first “PEGS and Wholes” editorial in 1995, Elkin challenged the new faddish attention to deliberation, asking: “if deliberation is such a good thing what does it take to get it?” That is a theme we take up again in this issue and to which we plan to return in future. Always The Good Society has had the dual aim to analyze specific institutions and understand them in relation to regimes: to understand that the structure of the economy, the organization of the state, and the role of the citizen are not independent but interlinked questions. Elkin titled his editorials “PEGS and Wholes” to refer to this linkage, framing analysis of the institutions within the good (or good enough) regime.

I intend to preserve that stereoscopic focus, with some expansions. The discipline of political science still seems to have its attention focused elsewhere, or what’s worse, research questions are divided up in such a way that the question of the good political regime is rarely asked in its totality. Yet it is not hard to find fellow-travelers: many scholars find themselves straddling disciplinary lines in the way Elkin imagined, and we will continue to be a home for their work. In our coverage of the good regime, economy and government authority have predominated, and citizenship has often played a minor role. Yet there is good reason to believe that insofar as a regimes’ institutions fall short of those required for a good enough regime, only the regimes’ citizens, acting together, can restore it.

The Good Society has assembled plenty of evidence about which institutions citizens should seek to reform, and even some theories as to how they should go about achieving those reforms. But more than before I hope to find good work to publish in The Good Society on the education, organization, deliberation, and effective action of citizens (defined both as legal members and as informal co-creators of the institutions and regimes they inhabit.)

I believe that one of the primary obstacles to effective citizen action is the size of the problems and the mechanisms available to address them: neither small-scale deliberative and participatory activism nor mass-scale mobilization and protest are any longer effective to address the kinds of problems that plague us. We therefore welcome new work on challenges to citizen efficacy, especially challenges and opportunities presented by the administrative state, whether it be in environmental governance, financial sector rule-making, or urban land use.

We will also spend a bit more time focusing on bad regimes and the badness in our own. This issue features a book review on a new biography of Adolph Eichmann that purports to challenge Hannah Arendt’s 1963 portrait of the man in Eichmann in Jerusalem. As Roger Berkowitz reports, it mostly confirms her thesis that Eichmann was anti-Semitic and cruel, but ultimately thoughtless. Hannah Arendt said of political theory that it takes up the challenge “to think what we are doing.” Eichmann, she claimed, did not think what he was doing and so while he was guilty of enthusiastic support for genocide, this guilt was a byproduct of his thoughtlessness and failure of imagination. The corollary for Arendt was that when our own thoughtlessness fails to be genocidal it is more a matter of (moral and institutional) luck than skill or character, so “thinking what we are doing” is a general obligation.

While we may not have been unthinkingly complicit in genocide, we have inhabited a regime that incarcerates far too many of its citizens, too many of whom are black and brown and poor. We have inhabited a regime that has become dependent on a class of migrant laborers who are denied the formal rights and protections of citizenship. And we have inhabited a regime whose consumption patterns appear to be inconsistent with sustaining a good (or even good enough) climate. There is little doubt that even the good enough society is an aim to be secured rather than a status quo to be maintained, and there are many more examples like these in the political economy and institutional design of our own regimes.

Thus while we continue to value the kind of political theory that aims to think the present moment, to understand how we have found ourselves in this place, we hope to expand “what are we doing?” to include the question of civic studies: “what shall we do together?” This opens up strategic considerations and alternative aims in a way that was always nascent in the effort to secure and maintain good political regimes. But it also frames future research around the limits and opportunities for citizens to reconstruct the regime’s constitution directly. I want to put contributors on the lookout for spaces and examples of collaboration among active citizens that reach beyond the limited scale of local citizenship.

Some Procedural Changes of Note

Two Departures from the Symposium Model: Historically, The Good Society has solicited and published thematically-linked symposia. The beauty of this model is the depth of inquiry that scholars can produce when they are engaged together from the start in attacking a single theme from multiple perspectives. As much as possible, we plan to preserve this model; but we also plan to expand on it. Starting this issue, we will begin announcing our themes in advance and soliciting papers broadly. We will also begin publishing standalone papers and book reviews, as well as symposia from prior issues.

Calls for Papers: Over the next year we’ll be publishing symposia on a diverse set of themes: formal political theory, militaries and democracy, and deliberation in non-democratic regimes. We invite contributions to these symposia, especially from young scholars. We promise to give prompt peer reviews (within the limits of our reviewers’ generosity and competence.) The quickest way to access these calls for papers is through our new website (goodsocietyjournal.org) and our Facebook page (The Good Society.)

A General Call for Standalone Papers: Starting this year, we will be experimenting with the publication of standalone papers. One way to think about these papers is as responses to prior symposia: if you missed the publication deadline for our symposium on “Mass Incarceration and Democratic Theory,” for instance, we would still like a chance to publish your response essay or your article on similar themes. Another way to think about this standing call for papers is through the lens of our enduring preoccupations: in this issue, you will find the first publication of a document we call “The Framing Statement,” written by a group of scholars as they began planning the Summer Institute for Civic Studies that now meets annually at Tufts. You may also consider it a general call for papers, symposia, reviews, and practical reflections.

Triannual Publication: The Good Society has sometimes been published biannually and sometimes triannually. Starting in 2016, it will be published triannually again, thanks to our new partnership with the Kettering Foundation.

Endnotes, In-Text Citation, and Abstracts: We’ve traditionally eschewed the clutter of in-text citation, along with that harbinger of indexing and impact factors, the abstract. But no longer. We now welcome in-text citations and require abstracts.

PEGS and The Good Society: Since 1995, the proper title of the journal has been “The Good Society: Journal of the Committee on the Political Economy of the Good Society.” That’s quite a mouthful! So in private we call the journal “The Good Society,” a name we share with a German denim clothing brand and books by Walter Lippmann, Robert Bellah (and his coauthors), and John Kenneth Galbraith. PEGS generally refers to the Committee and its work: the edited volumes, our panels at the APSA and other conferences, etc.

Biases, Heuristics, and Democracy

This issue features a symposium on “Biases, Heuristics and Democracy.” The current cross-pollination between cognitive psychology, experimental philosophy, and political science has been a very fruitful one for researchers, but we worry that it has overemphasized the basic skepticism in political theory about the competence of democratic polities. So we commissioned these papers to take up the newest version of Plato’s challenge that the demos is not wise enough to rule.

Perhaps the best and most appealing expression of this view comes from Cass Sunstein, who has gathered the research on democratic deliberation and epistemic considerations for public policy in such a way as to make a preference for democratic decision-making look unpalatable.[ii] Yet as Michael Wagner and his co-authors show, citizens need to use their cultural identities as a part of their reflection and deliberation, and these identities can both help and hamper comprehension. Heuristics, then, are not simply biased short-cuts, but lenses through which we see and frame the world: there is no non-heuristic cognition. In the spirit of operationalizing the problem, John Gastil offers concrete suggestions from his research on the Oregon Citizens Initiative Review for institutional changes that can increase voter information without succumbing to bias. With a theorist’s perspective, Hélène Landemore adds insights from her own recent book to this defense, arguing that the existence of biases actually militates in favor of inclusion and broad-based decision-making rather than exclusion. And Jamie Kelly takes issue with Sunstein’s libertarian paternalism, not from the perspective of libertarian concerns for autonomy, but rather from the perspective of the common welfare.

[i] Stephen L. Elkin, Reconstructing the Commercial Republic: Constitutional Design after Madison (Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 2006), 3.

[ii] Cass R. Sunstein, Republic. Com 2.0 (Princeton University Press, 2009); Cass R. Sunstein, “The Law of Group Polarization,” Journal of Political Philosophy 10, no. 2 (2002): 175–95; Cass R. Sunstein, “Moral Heuristics,” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 28, no. 4 (2005): 531–41; Cass R. Sunstein, Why Nudge?: The Politics of Libertarian Paternalism (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2014).

“Resilient Communities” Conference Call from CM, Jan. 22

We are pleased to invite NCDD members once again to join CommunityMatters – a joint partnership that NCDD is proud to be a member of – for the next installation in their capacity-building call series. This month’s call on “Resilient Communities”,  and it will be taking place on Thursday, January 22nd, from 2-3pm Eastern Time.

and it will be taking place on Thursday, January 22nd, from 2-3pm Eastern Time.

The folks at CM describe the upcoming call like this:

Our communities are constantly changing. Most changes are gradual and predictable – a new store opens on Main Street, newcomers come to town and priorities shift. But, sometimes change is abrupt, unexpected – a major natural disaster or an epidemic.

How can your city or town best prepare for unanticipated change? What will help your community respond to challenges not only to bounce back, but to become stronger than ever?

Michael Crowley, senior program officer, Institute for Sustainable Communities, and Christine Morris, chief resilience officer with the City of Norfolk, Virginia, join CommunityMatters for an hour-long conference call on January 22. They’ll share ideas about and lessons learned from building resilient communities.

We highly encourage you to save the date and register for the call today by clicking here.

Before you join the call, we also suggest that you check out the blog piece on boosting community resilience that Caitlyn Davison recently posted on the CM blog to accompany the call. You can read her piece below, or find the original here.

We hope to hear you on the call next week!

7 Ways to Boost Your Community’s Resilience

Do you know what’s around the corner for your community?

Community resilience is about making our cities and towns less vulnerable to major and unexpected change, and establishing positive ways to face change together.

Resilient communities build on local strengths to anticipate change, reduce the impact of major events, and come back from a blow stronger than ever.

What steps can your community take toward resilience? Here are seven ideas from cities and towns working to boost local resilience.

1. Stop, collaborate, and listen. Focus on how people in your area collaborate. In trying times, people in resilient communities mobilize quickly, working together to solve problems and help each other. Promote neighbor-to-neighbor cooperation through collaborative efforts like a community garden, seed library, tool sharing, or solar co-op.

2. Put a dot on it. The Carse of Gowrie area of Scotland is engaging residents in identifying local strengths through community resilience mapping. Residents used online software to map assets in light of potential climate change risks and opportunities. The maps help locals visualize their community and provide valuable data for decision-making.

3. Set an agenda for resilience. To kick-start community conversations about resilience in Norfolk, Virginia – one of the Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities – the city hosted an Agenda-Setting Resilience Workshop. The workshop brought together community leaders and residents to discuss the interconnected impacts of local stresses and shocks, including rising sea level and recurrent tidal flooding. Feedback from the workshop will inform the city’s resilience plan.

4. Create a local resilience task force. In New York’s Hudson Valley, non-profit Scenic Hudson formed a task force to plan for sea level rise and flood-resistant waterfronts. The task force’s final report outlines general and site-specific recommendations that promote resilient and thriving waterfront communities.

5. Practice your plan. You might have the slickest emergency plan ever written, but it isn’t going to do your town much good if no one else knows about it. Still recovering from Superstorm Sandy, the community of Red Hook, New York isn’t messing around. After developing an emergency response plan based on community members’ experience during Sandy, the Red Hook Coalition organized Ready Red Hook Day, a fun practice event to walk through the plan and visit local response stations.

6. Talk about communication during crisis. When a disaster strikes, will people in your community know about it? How will they let others know they are okay, or that they need assistance? In San Francisco, grassroots resilience planning helped develop a simple system for the elderly to communicate – a green door hanger indicates everyone got out safely; red means help is needed.

7. Plan big. Communities in Vermont know that planning for resilience at the local level might not be enough – they experienced crisis first-hand after Hurricane Irene devastated large parts of the state in 2011. Resilient Vermont, led by the Institute for Sustainable Communities, is working to develop an integrated, long-term strategy for resilience that weaves together state, regional, and local initiatives.

On January 22, Michael Crowley, senior program officer, Institute for Sustainable Communities, and Christine Morris, chief resilience officer with the city of Norfolk, Virginia, join CommunityMatters® for an hour-long talk on community resilience. You’ll find tools and lessons learned for boosting resilience in your area. Register now.

You can find the original version of this CM blog piece at www.communitymatters.org/blog/7-ways-boost-your-community%E2%80%99s-resilience. You can find more information on the “Resilient Communities” conference call at www.communitymatters.org/event/resilient-communities.

The Newly Launched Commons Transition Plan

The P2P Foundation recently launched a new website, the Commons Transition Platform, as a central repository for policy ideas that help promote a wide variety of commons and peer-to-peer dynamics. The site represents a new, more coordinated stage of activism in this area – collecting practical policy proposals for legally authorizing and encouraging the creation of new commons.

The website is a database of “practical experiences and policy proposals aimed toward achieving a more humane and environmentally grounded mode of societal organization.” The idea is to begin to outline how policies could bring about and support a commons-based civil society, with a special focus on how collaborative stewardship of shared resources can be achieved.

The P2P Foundation has stated its aspirations for the new initiative this way:

With the Commons Transition Plan as a comparative document, we intend to organize workshops and dialogues to see how other commons locales, countries, language-communities but also cities and regions, can translate their experiences, needs and demands into policy proposals. The Plan is not an imposition nor is it a prescription, but something that is intended as a stimulus for discussion and independent crafting of more specific commons-oriented policy proposals that respond to the realities and exigencies of different contexts and locales. This project therefore, is itself a commons, open to all contributions, and intended for the benefit of all who need it.

The Commons Transition Platform currently features three main policy documents, each originally created for Ecuador’s groundbreaking FLOK Society Project. The FLOK Project (Free Libre Open Knowledge) produced a comprehensive set of policy proposals for encouraging knowledge commons and peer production. These documents – written by Michel Bauwens, John Restakis and George Dafermos – have been newly revised and updated in non-region-specific versions.

E=MC^2

Einstein’s famous formula is truly a work of art.

Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that nature is a work of art, but the beauty that can be contained in a seemingly simple mathematical formula is truly astounding.

I have a very distinct memory of learning the famous E=MC^2 equation in high school, at which point it was explained something like this:

Energy equals Mass times the Speed of Light squared. That means that the amount of energy in a hamburger (yes, that was the example) is equal to the mass of that hamburger times the the speed of light squared. The speed of light in a vacuum is 299,792,458 m/s, so that number squared is really really big. Therefore the amount of energy in a hamburger is really really big.

Mind = blown.

Well, sort of.

The above description is accurate and it is, in fact, remarkable that so much energy could be contained in something of small mass. But that explanation is so flat, so uninspiring, so…uninformative.

Why should anyone care that energy equals mass times the speed of light squared? And what does the speed of light have to do with anything? It is just some magic number that you can throw into an equation to solve all your problems and sound really smart?

The famous E=MC^2 equation is the most practical form if you’d like to calculate energy, but I personally prefer to think in terms of that mysterious constant, c:

The speed of light – in a vacuum, a critical detail – is equal to the square root of energy over mass.

That is to say, energy and mass have an inverse relationship, and their ratio is constant. That ratio is the square of the maximum speed an object with no mass can travel –

The speed of light in a vacuum.

everyone unique, all connected

Reading my sister Caroline Levine’s extraordinary new book Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network, I’ve been reflecting on similar ideas that I have come to quite independently.

In college, I was deeply struck by the argument that human beings (whatever we all share as members of the same evolved species) are also divided into large clusters whose members think alike in important respects but differ with outsiders. Those clusters can be called cultures, worldviews, Weltanschauungen, etc. That these groupings are internally consistent but different from one another is an essential premise of philosophers like Hegel and Herder, of founding anthropologists like Boas and Malinowski, of New Historicist critics like Catharine Gallagher and Stephen Greenblatt, and even of deconstructionists who seek to rupture such “bounded wholes” (see Caroline Levine, pp. 26, 115-16). I’ve found the same assumptions elsewhere, too. The influential psychologist Jonathan Haidt assumes that each person subscribes to a “moral matrix” that “provides a complete, unified, and emotionally compelling worldview, easily justified by observable evidence and nearly impregnable to arguments from outsiders.” And (although different from Haidt in most other respects) John Rawls called a “plurality of reasonable but incompatible comprehensive doctrines” a “fact” about the world.

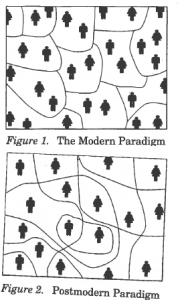

At one moment during the summer of 1989 (crossing the street in Rosslyn, VA), I thought: But each of us belongs to many of these clusters at once. The clusters overlap; their borders cross. In fact, even twin siblings would have somewhat different influences and assumptions. I drew this pair of diagrams, which appear in my Nietzsche and the Modern Crisis of the Humanities (1995, p. 188-9).

I favored what I pretentiously called the “postmodern paradigm” of fig. 2 and claimed that it dispelled some of the dilemmas of value-relativism and skepticism that bedeviled modernity. This was before the large literature on “intersectionality” really got going. I agree with the argument that (for example) race, gender, and class can “intersect,” but I would push that to its limit. Our backgrounds intersect in so many ways that everyone stands at a unique intersection.

Now I am more likely to draw a different kind of map, one that treats each person’s mentality as a network of ideas, such that the nodes are typically shared by people who interact, but each person’s overall network is unique. (This is the map of the ideas identified by my students in a recent class. Each student is displayed in a different color, and their networks touch where they disclosed the same idea.)

Caroline would describe figs. 1-2 as sets of bounded wholes, and the third diagram as a network map. Wholes and networks are two fundamental forms in her account–she also investigates rhythms and hierarchies. Indeed, the two forms I display above are limited in two respects. They are time-slices that fail to capture change. (Rhythm is missing.) And they are all about ideas and values, not about institutionalized forms, such as hierarchies. I think she is correct that all four types of form–and no doubt more as well–overlap and contend, creating the structures in which we live but also offering opportunities for emancipation if we figure out how to put them together in new ways.

The post everyone unique, all connected appeared first on Peter Levine.