As we are watching the attendees gather today for the start of NCDD 2014 in Reston, VA, it is a sight to see. Over 400 dialogue, deliberation, and public engagement professionals are coming together to work and learn together, and we couldn’t be more excited!

In the spirit of honoring all that our wonderful NCDD community represents, we wanted to share a thoughtful piece adapted from a talk NCDD Board member Susan Stuart Clark gave at San Rafael City Hall on September 26, 2014 to a local community group about the movement we are building with NCDD. You can read it below or find the original here.

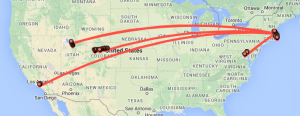

Map of the National Coalition for Dialogue and Deliberation network

NCDD: The Invisible Movement

Shhh…can you hear that?

It’s the sound of an invisible movement. Over 30,000 people across the U.S. and Canada are engaging thousands – and, at times, millions – in doing something that most people have no idea is happening.

What are they doing? They’re leading conversations – a different kind of conversation that challenges the assumption that our society is getting ever more divided. This is a network of thousands of innovators who bring people together across divides to tackle today’s toughest challenges.

At the center of this growing network is the National Coalition of Dialogue and Deliberation. NCDD is a non-profit organization that provides resources for people who plan and lead meaningful conversations that help find common ground for action on important issues that affect all of us.

1. Who are these people and what are they doing?

The NCDD network is made up of a wide variety of group facilitators, professors, students, government officials, organizational development consultants and committed volunteers. While the range of backgrounds is diverse, NCDDers share a common dedication to creating opportunities for people to talk, listen and act together in new ways – ways that build deeper understanding and create new openings for solving problems.

NCDD is non-profit and non-partisan. We are not advocates for any particular position – instead we are advocates for more constructive and inclusive process.

NCDDers might be leading dialogues about health care, schools, land use decisions or the environment. And these conversations can be taking place in community centers, in churches, county or town council chambers or in classrooms – with community members from all kinds of backgrounds and often with translation. What binds us together is that we believe that inclusive dialogue can generate shared understanding and shared goals – and that shared understanding is the “secret sauce” for new possibilities and new paths forward that can help us make progress as we join forces rather than waste energy on divisive debates.

The “deliberation” part of this work is when we frame up a topic by acknowledging the real choices and trade-offs at hand – whether it’s about the drought, increasing educational opportunities for all kids and the workforce of the future or what should get built where. In deliberation, we make sure that these tough choices are informed by the perspectives of everyone who is impacted and by the values we as a society decide will shape our decisions.

2. Why haven’t you heard of us?

Here are my theories:

A. Dialogue and deliberation are not embedded in the formal structures of our democracy. We vote yes or no on ballot measures. We often choose between two candidates. We are well versed in a thumbs up/thumbs down kind of thinking that leads to winners and losers. In a debate, you listen to hear your opponent’s weakness. But in a dialogue you listen to learn from each other.

At the local level of our democratic systems, we have public hearings. But taking turns for three minutes at the microphone is not the same as a dialogue where community members can set the framework for what’s important and explore and ask for clarifications from each other to see where we agree and don’t agree.

B. If you want the kind of dialogue I’m talking about, someone has to go outside the norm to set it up, find the resources, plan it and convince people something good is going to come out of it. But most people have rarely if ever had this experience of genuine public dialogue, which makes it harder to convince them to participate.

So our invisible movement of NCDDers is finding ways to set up these experiences so people can feel what it’s like to come together and learn from each other and discover that the “other” can be an ally. The problems we face may not be easy – but there are solutions when we can talk about them in constructive ways with a broad range of the affected community.

C. Facilitators don’t draw attention to themselves. When I do my job well as a facilitator, I fade into the background as I let the group do its work. When I first started out, my facilitation was more visible, like the old yellow version of scotch tape. But the better I get, the more invisible I become and the meeting participants remember their experience rather than my expertise.

3. Why do we persist in this work?

Because we know that most people outside of the political system are looking for connection, and practical solutions to the pressing issues of our day. And as the size and complexity of our challenges keeps expanding, we know that more inclusive and collaborative dialogue can generate more effective and longer lasting solutions.

As we go through yet another election season, with divisive campaigns that purposefully use wedge issues to isolate groups from one another, and a news industry perpetuating a tired old strategy of selling conflict and controversy, people are left to wonder if a new politics is possible. NCDD operates on the premise that it IS possible because we are planting and nurturing the seeds that we see growing every day in communities across the country.

4. What can you do?

Visit NCDD.org to see how we work to change how we do democracy. Look at the map and the extensive set of resources to see who in your area and/or on your issue of interest is working hard to make a difference.

Check out the amazing array of presenters and projects featured at our biennial conference this weekend (October 17-19) in the Washington DC area. Over 400 leaders young and old are connecting our work and our passion for the “Democracy for the Next Generation.”

Consider joining NCDD – it’s just $50 between now and Election Day. NCDDers are in the “parallel universe” of what democracy can be like. Your membership is like a vote that makes this alternate reality more visible to all.

And, next time you hear someone say “that’s just politics” and throw up their hands, I ask you to instead engage them in a dialogue about what they think is important. Maybe you’ll find some common ground. And that leads to new possibilities to change the world.

________________

Susan Stuart Clark is founder and director of Common Knowledge. She serves on the board of the National Coalition for Dialogue and Deliberation. You can find the original version of this piece on her blog at www.ckgroup.org/2014/10/16/the-invisible-movement.

But what’s really at work is adverse selection: chasing great schools, the middle class follow each other from the city to the suburbs and back again, and from neighborhood to neighborhood within the city.

But what’s really at work is adverse selection: chasing great schools, the middle class follow each other from the city to the suburbs and back again, and from neighborhood to neighborhood within the city.