We might like to think that when we form a belief, it comes after we have reviewed reasons. We canvass all the relevant reasons (pro and con), evaluate each of them, weigh and combine them, and choose the belief that follows best. In that case, our reasons cause our beliefs, whether they are about facts or about about values. We might also like to think that when someone offers a strong critique of our reasons, we will be motivated to change our beliefs.

A wealth of empirical evidence suggests that this process is exceedingly rare. Much more often, each of us forms our beliefs intuitively, in the specific sense that we are not conscious of reasons. It feels as if we just have the beliefs. Then, if someone asks why we formed a given belief, we come up with reasons that justify our intuition. We may even ask ourselves for reasons when we wonder why we had a thought.

This process is retrospective. We did not already have reasons. We find them to justify or rationalize our intuitions to ourselves or to other people (Graham, Nosek, Haidt, Iyer, Koleva, & Ditto 2011, p. 368; Haidt 2012, pp. 27-51; Swidler 2001, pp. 147-8; Thiele 2006).

This theory is concerning. For one thing, if you are already sure of any belief, then you can probably find a plausible reason to justify it and a plausible rebuttal to any critique. We don’t sound like very rational or reasonable creatures, ones who are good at assessing and combining reasons and drawing appropriate conclusions. We sound like lawyers in our own defense, finding grounds to justify what we merely assumed even when the evidence is weak.

Further, all the explicit discourse that we observe around us–all those meetings and articles and legal briefs and speeches and sermons–begins to seem like a foolish waste of effort. It’s the noise of people rationalizing what they already thought.

Some would add that intuitions about moral and political matters often seem to reflect self-interest. The rich are intuitively favorable to markets; men are biased for patriarchy; Americans, for the USA. In that case, reasoning is moot. The causal pathway runs from interests to intuitions and from there to justifications, and the justifications accomplish very little.

This highly skeptical view of reason results from focusing on individual human beings at the moment (or within a short timeframe) when they form beliefs. When we look outward from such moments, we find human beings meaningfully exchanging reasons that matter.

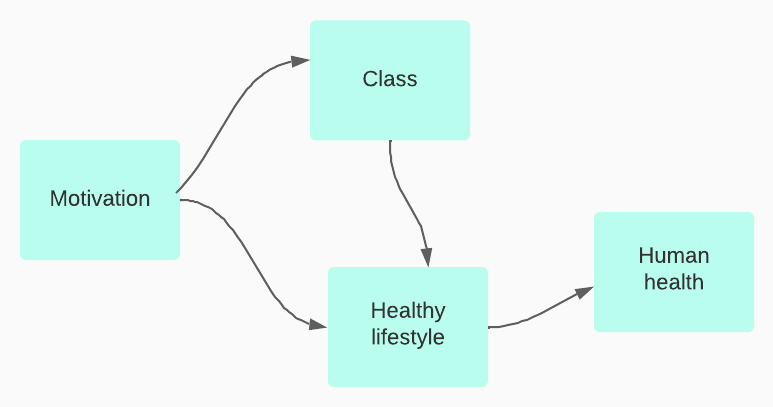

First, let’s look before the moment of intuition. Where did it come from? Let’s consider, for example, a person who hears about a proposed new federal program and has a strong intuition against it. This person may not explicitly consider reasons for and against federal intervention; the intuition may arise automatically. But before the moment of intuition, this person had probably heard many explicit critiques of government. Maybe a parent made a memorable complaint about the government when this person was still a child, and that attitude was reinforced by speeches, articles, stories, and other forms of intentional discourse. This individual may also have had direct, personal experiences, such as facing a burdensome regulation or having an unpleasant encounter with a bureaucrat. However, we must interpret such experiences using larger categories (such as “regulation” and “bureaucrat”) that we get from other people.

This process of forming an attitude that then generates an intuition may be more or less reasonable. The attitude might be wise and well-substantiated or else a mere prejudice. My point is not that people reason well but that discourse is often prior to intuition (cf. Cushman 2020). People’s intuitions about matters like government programs are influenced by the prevailing discourses of their communities. It matters whether you came of age in a neoliberal market economy, under collapsing state communism, in a stable social democracy, or in a Shiite theocracy. In this sense, reasons influence intuitions, but they may not be reasons that an individual explicitly considers before forming a belief. Rather, reasons circulate in the discourse of a community.

Now let’s look after the moment of intuition, to the time when a person answers the question: Why? For instance, why are you–or why am I–against this government program? The individual begins to generate reasons for the original intuition: Government never works well. Taxes are already too high. It’s not fair that lazy people should get a free ride — etc. These reasons were not in the person’s head prior to the intuition, and they did not cause it, yet they matter in several ways.

First, as intensely social creatures, we use reasons to establish our value to groups. People who can offer reasons that sound plausible, consistent, or even insightful emerge as respected and have influence. Sometimes, glib sophists gain respect with reasons that shouldn’t impress others, but to a significant extent, we judge other people’s reasons well (Mercier & Sperber 2017). We did not evolve to be magnificently rational thinkers who reach our individual judgments solely on the basis of evidence, but we did evolve to be remarkably perceptive social mammals who are pretty good at judging each other.

Hugo Mercier and Dan Sperber write:

Whereas reason is commonly viewed as a superior means to think better on one’s own, we argue that it is mainly used in our interactions with others. We produce reasons in order to justify our thoughts and actions to others and to produce arguments to convince others to think and act as we suggest. We also use reason to evaluate not so much our own thought as the reasons others produce to justify themselves or to convince us (Mercier & Sperber 2017, pp. 7-8).

Because we want to be respected for our judgments, we will go to considerable effort to rationalize our intuitions. That effort can take the form of skillful defense-lawyering: cleverly finding tendentious grounds for our positions. But it can also lead us to revise our beliefs because we do not want to be caught with inconsistencies, selfish biases, or blatant factual errors. Revision is less common than we would assume if people were ideally rational, but it occurs because we care about our reputations (Mercier & Sperber 2017, p. 146).

We are also motivated to find and express good reasons because doing so affords influence. For one thing, we can shape other people’s intuitions later on. The parent who told her child not to trust the government was trying to influence that child’s intuitions, as were other people who spoke on both sides of the issue later in the same person’s life.

Human beings can assess the cogency of other people’s explicit reasons, not with perfect reliability, but often pretty well. That means that if you have an intuition that you want other people to share, a good strategy is to come up with coherent reasons that support it. Good reasons may not overcome bias against you or favoritism for others. They may not overcome raw power, money, or lies. But they raise one’s odds of being influential, which is a source of power. Whether valid reasons persuade depends on how well our institutions are designed, and properly deliberative institutions are ones that reward the giving of good reasons (Habermas 1962, 1973).

Finally, when reasons are widely expressed and rarely opposed, they become norms, and norms are crucial for cooperation. For instance, in large swaths of an advanced liberal society, there are now explicit norms against gender discrimination. These norms are compatible with: 1) privately held explicit sexist opinions, 2) unrecognized or implicit sexist biases, 3) blatantly sexist subcultures, and 4) bad reasoning, such as neglecting to consider gender when reaching a conclusion about a policy. Nevertheless, the norm against gender discrimination exists and matters. Official policies are measured against it, and bodies like courts and school systems are affected by it. In turn their policies affect people’s mentalities over time.

Norms have the additional advantage that they do not have to be stated. This is crucial because we are not able to express all the premises of our arguments. In justifying what we believe, every point we can make depends on other points, which depend on others, pretty much ad infinitum; and we cannot address that whole web. Instead, we must assume agreement about most of the context. In Paul Grice’s terminology, we “implicate” beliefs that we assume others share (Grice 1967).

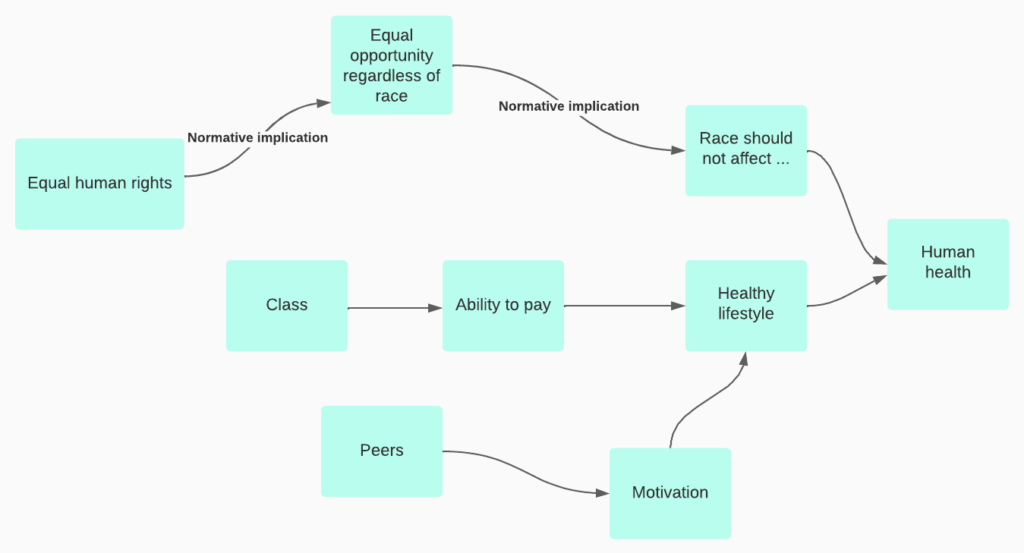

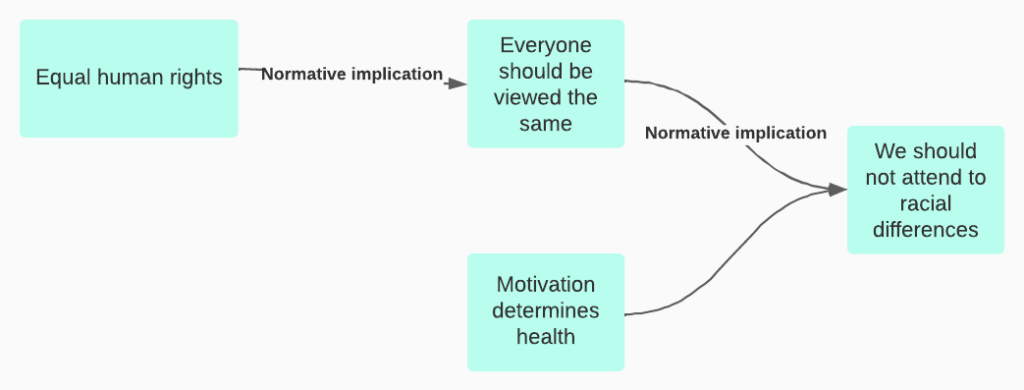

You can recognize the power of implicature when it goes wrong because the speaker’s belief is not working as a norm. For example, the phrase “Black Lives Matter” implicates the (true) premise that black lives have not been valued and that black people face pervasive discrimination and violence. Surveys show that a majority of white Americans do not believe this and even think the opposite, that whites face more discrimination. I suspect that at least some of them really don’t hear the implicature. They take “Black Lives Matter” to mean that only black lives should matter.

This is a troubling example at several levels, but it does not suggest that we lack norms entirely. On the contrary, our discourse is pervaded with shared assumptions, many of which developed over time as a result of intentional argumentation and persuasion. We can now implicate that violence is undesirable or that nature is precious even though both beliefs were widely rejected a century ago. Again, the norm that violence is bad can coexist with much implicit and hypocritical support for violence and with subcultures that openly promote violence. But it still has power as a belief that most people in many contexts can assume most other people publicly endorse, i.e., as a norm.

In turn, forming and shaping norms is a matter of grave significance, and reasons are tools for influencing norms. The paradigmatic case of reasoning is not an individual who identifies reasons and reaches an appropriate conclusion, but a community that shifts its norms when they are explicitly contested in public speech.

As Mercier and Sperber write:

Invocations and evaluations of reasons are contributions to a negotiated record of individuals’ ideas, actions, responsibilities, and commitments. This partly consensual, partly contested social record of who thinks what and who did what for which reasons plays a central role in guiding cooperative or antagonistic interactions, in influencing reputations, and in stabilizing social norms. Reasons are primarily for social consumption (Mercier & Sperber 2017, p. 127).

This is basically an empirical account of what the species homo sapiens does when we offer what we call “reasons.” It does not tell us how good this process is, in other words, whether it is a procedure that generates sound or valid results. Assessing human reasoning feels increasingly urgent now that we also have machines that generate sentences that convey reasons by using different procedures from ours.

Assessing our activity of reasoning requires epistemology, not empirical psychology alone. Fortunately, we have a sophisticated philosophical account of reasoning that is broadly consistent with the empirical account of Mercier and Sperber (Fenton 2019).

Robert Brandom argues that any claim (any thought that can be expressed in a sentence) has both antecedents and consequences: “upstream” and “downstream” links “in a network of inferences.” For instance, if you say, “It is morning,” you must have reasons for that claim (e.g., the alarm bell rang or the sun is low in the eastern sky) and you can draw inferences from it, such as, “It is time for breakfast.” (This is my example, not Brandom’s.) Reasoning is a matter of making these connections explicit. When making a claim, we propose that others can also use it “as a premise in their reasoning.” That means that we implicitly promise to divulge our own reasons and implications. “Thus one essential aspect of this model of discursive practice is communication: the interpersonal, intra-content inheritance of entitlement to commitments.” In sum, “The game of giving and asking for reasons is an essentially social practice.”

For Brandom, the same logic applies to “ought” claims and other normative sentences as to factual claims: whenever we make a statement, including a value-judgment, we owe a discussion of its reasons and implications. Brandom suggests that communication can be inward: we can reason in a “hypothetically” social way by thinking in our heads. But I would add—based on a safe empirical generalization about human beings—that we are quite bad at seeing the reasons for and the implications of our judgments about ethical and political matters that affect other people. Therefore, we badly need actual social reasoning: giving reasons and listening to the real reactions from other people (Brandom 2000, Kindle locs. 1733, 1746-7, 1767-9, 2060, 1799).

See also opinion is dynamic and relational; in defense of (some) implicit bias. Sources: Cushman, Fiery. “Rationalization is rational.” Behavioral and Brain Sciences 43 (2020); Graham, Jesse, Nosek, Brian A., Haidt, Jonathan, Iyer, Ravi, Koleva. Spassena, & Ditto, Peter H. 2011. Mapping the Moral Domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101; Fenton, William (2019), “On the Philosophy and Psychology of Reasoning and Rationality,” Kent State MA thesis; Grice, Paul, “Logic and Conversation” (1967), in Grice, Studies in the Ways of Words (Harvard, 1989), pp. 22-44; Habermas, Jürgen. (1962) 1991. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere: An Inquiry into a Category of Bourgeois Society. Translated by Thomas Burger. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; Habermas, Jürgen. (1973) 1975. Legitimation Crisis. Translated by Thomas McCarthy. Boston: Beacon Press; Haidt, Jonathan. 2012. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York: Vintage; Mercier, Hugo and Dan Sperber, The Enigma of Reason, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press 2017; Swidler, Ann. 2001. Talk of Love: How Culture Matters. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; Thiele, Leslie Paul. 2006. The Heart of Judgment: Practical Wisdom, Neuroscience, and Narrative Cambridge University Press.