In “People deserve safety on college campuses, ideas don’t,” Andrew J. Perrin and Christian Lundberg make an important argument against the idea of viewpoint diversity. They write:

Emphasizing viewpoint teaches students to not bother separating ideas from the people who hold them. Viewpoint is a visual metaphor that attaches what a person believes to where they sit: Viewpoints are properties people own and express, not ideas to be evaluated. It’s a classic ad hominem fallacy that renders argument fruitless.

We all draw on experience, and our experiences are influenced by our social positions. That is why demographic diversity is intellectually valuable. If, for example, men monopolize the conversation, then issues and solutions that are more obvious to other genders will probably be overlooked, or, at best, underplayed. The fact that some individuals demonstrate exceptional insight into others’ experiences does not negate this point. (See “Dear Mrs Amartya Sen, men will never understand us.”)

However, the metaphor of a viewpoint makes people’s ideas look like automatic functions of their social positions. It overlooks the diversity and freedom of individuals in any given social group; it makes reasoning and argument look fruitless; it implies that incorporating individuals with additional viewpoints will automatically improve a group and should be the main goal; and it suggests that a critical assessment of an idea is an attack on the person who holds it. As Perrin and Lundberg conclude:

Settling for exposure to viewpoints — as if they were infections to which one might develop antibodies — places them outside the realm of argument and reason. We fail those on the political left by ignoring conservative arguments instead of engaging them. Meanwhile, conservative students learn that their ideas are something others should be exposed to rather than meaningfully engaged.

I believe that the metaphor of a viewpoint is deeply rooted, and that challenging it could be quite fruitful. Put more generally, the image of a point in space is remarkably widely used to define people and ideas.

The most familiar example is the left-to-right political spectrum, which allows a person, an opinion or position, or a party or movement to be located at one point on a straight line. People or ideas can easily be visualized as points in two-dimensional space if they are located along two axes at once. For instance, Americans have often been described as liberal versus conservative on economics and on race, as two separate dimensions. Three dimensions are harder to depict on paper or a flat screen, although a three-dimensional model can be rotated and presented meaningfully on a plane. In any case, mathematics allows adding more than three dimensions, even though we can’t picture them visually, by simply tagging a given person, idea, or party or movement with many variables at once. Prevailing statistical methods, such as factor analysis, treat people, ideas, or groups as points in many-dimensional space and envision differences as the distance between positions. Many models try to explain why a person occupies a given point based on other known information about the same individual, such as party identification or race.

If a model employs many dimensions, it can incorporate any amount of quantitative data about the people and ideas being studied. Since each person or idea has a good chance of occupying a unique position in multidimensional space, there is relatively little danger that individuals will be casually lumped together in large groups.

However, some kinds of information must be lost in a model based on points in space. First, this metaphor conceals the way that ideas may connect to each other. If respondents are asked many questions on a survey, standard statistical methods capture correlations among their answers but cannot detect logical relationships among any individual’s ideas. Does a person believe one thing because of another belief, or despite it, or as two disconnected ideas? The structure of individuals’ thinking—if there is any—is lost. In contrast, when we read an impressive political argument or speech, we are primarily interested in its structure: in why (or whether) each point implies the next, or qualifies it, or contradicts it. A metaphor of points in space makes everyone look much more simple-minded than any careful speaker or writer.

To be sure, some of us probably fail to connect our separate ideas in reasonable ways, but we cannot know how many from standard survey research. The metaphor of points in space is biased against detecting complexity of thought, if there is any (Levine 2022).

Importantly, large bodies of research based on this model find that people are not responsive to arguments, that their beliefs are either incoherent or driven by indefensible biases, that they supply reasons after the fact to rationalize what they already desire—in short, that anything remotely resembling a deliberative democracy is psychologically naïve. Paul Sniderman—who dissents in interesting ways from what he calls “the textbook view of citizens’ capacity to reason about politics”—summarizes the consensus of his fellow political scientists as follows. “Average citizens’ knowledge about politics and public affairs is threadbare; their political beliefs minimally coherent, indeed, often self-contradictory; their support for core democratic values all too likely to crumble in the face of a threat, real or imaginary” (Sniderman 2017, pp. 42, 107).

Factor analysis is a statistical technique. It is often described as scientific, where “science” means a cumulative, empirical research project of testing hypotheses with data. Famous contributors to the statistical study of political opinions and behavior who have used a point-in-space model are English-speaking social and behavioral scientists like Charles Spearman, who invented factor analysis, and Philip Converse and his colleagues, who pioneered academic political survey research with the American National Election Studies.

A strangely similar metaphor is also influential in a very different tradition: Continental European political philosophy. Until the late 1800s, the words “culture” and “religion” had made sense only in the singular. People either had culture or not; they were either religious or not. But Romantic-Era thinkers began to see deep plurality. There were many cultures, religions, and nations (or peoples), understood as distinct in fundamental ways. These thinkers imagined that individuals saw the world from the perspective of their respective cultures or religions. Two people from different cultures would behold a different reality, although people who shared a culture would share a common worldview. A word for everything that can be seen from a given point is “horizon.” Perspective, viewpoint, and/or horizon were keywords in the thought of Herder, Hegel, Marx, Nietzsche, Heidegger, and many other highly abstract European philosophers.

Again, a person with a perspective occupies a point in space. This metaphor generates insights—there may be a French, or a modern, or a bourgeois perspective on certain topics—but it also obscures and creates conundrums. If people hold all their beliefs because of their fundamental perspectives or viewpoints, then a critique of any of their beliefs can be taken as an objection to the person and their right to speak. In that case, arguments about ideas can seem uncivil and even threatening.

Furthermore, if human beings are assigned to cultures on a “one-to-a-customer basis,” (Wolcott 1991, p. 247), and if each culture fundamentally shapes how all its members understand the world, then how can anyone know anything objectively, including the nature of other people’s cultures? Surely everything we think is relative to our perspective. Deep cultural relativism leads to basic skepticism or even nihilism, as Nietzsche most famously argued.

One way out is to argue that a fair institution is one that treats all cultures and religions equally and neutrally. For instance, the great American political philosopher John Rawls assumes “that a modern democratic society is characterized … by a plurality of reasonable but incompatible comprehensive doctrines” (Rawls 1993, pp. xvi, 59). Each of these doctrines determines each person’s values. Rawls concludes that a fair government must be neutral among these doctrines; indeed, he sees justice as fairness. Demands for “viewpoint diversity” on college campuses have a similar logic. However, critics have argued that neutrality is impossible (liberal institutions inevitably reflect specific values) and mere fairness among perspectives is an unsatisfactory account of justice.

Whether it is invoked in a statistical model or a work of political philosophy, a point in space from which one sees the world is a metaphor. It should not be taken too literally. We have other ways of describing the complexity of human interactions. We can model conversations as games with players and moves. We can envision ideas flowing through society on a hydraulic model, with pressure and viscosity (Allen 2015). Caroline Levine shows that literary writing often makes use of four forms—wholes, rhythms, hierarchies, and networks—to represent social phenomena (C. Levine 2015).

Indeed, we live in a period of fascination with networks: electronic, neural, social, semantic, and many other kinds. This means that we have powerful new techniques for analyzing networks, and many recent studies apply these techniques to people and ideas in ways that offer insights about politics.

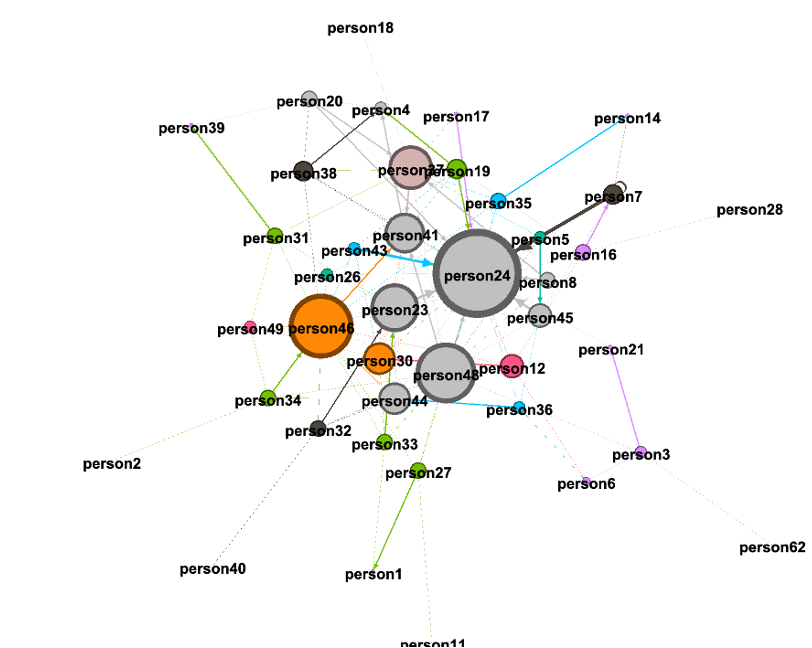

This is why I have been working with colleagues to replace the metaphor of points in space with one of networks. I have introduced the technical term idiodictuon for the network of ideas that each individual holds, where the connections among ideas are reasons.

In this model, when people discuss issues, they are sharing ideas and connections that others may choose to incorporate into their respective idiodictuons. Whether we encounter another person’s ideas depends on whether we are connected to that person in some kind of social network. Human beings who discuss within a network of relationships form a phylodictuon (a shared network of ideas, including ones that conflict).

It is generally good for a phylodictuon to encompass diverse ideas and ideas from diverse people (which are different matters), yet the job of a wise community is to improve its collection of ideas and how they are organized, not merely to ensure that all available ideas are included. As Perrin and Lundberg write, “Confronting serious ideas means that while every person deserves safety on campus, no idea does; all ideas deserve the respect that a real stress test brings.”

See also: individuals in cultures: the concept of an idiodictuon; Mapping Ideologies as Networks of Ideas; a mistaken view of culture; Teaching Honest History: a conversation with Randi Weingarten and Marcia Chatelain; etc.

Sources: Perrin, Andrew J. and Christian Lundberg, “People deserve safety on college campuses. Ideas don’t,” The Boston Globe, March 29; Paul M. Sniderman, The Democratic Faith: Essays on Democratic Citizenship (Yale University Press); Peter Levine, “Mapping ideologies as networks of ideas,” Journal of Political Ideologies, 2022, DOI: 10.1080/13569317.2022.2138293; Harry F. Wolcott, “Propriospect and the acquisition of culture., Anthropology & Education Quarterly 22, no. 3 (1991): 251-273; John Rawls (Political Liberalism. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993); Danielle Allen, “Reconceiving Public Spheres: The Flow Dynamics Model,” in Allen and Jennifer S. Light, From Voice to Influence: Understanding Citizenship in a Digital Age, University of Chicago Press, 2015, pp. 178-207; Caroline Levine, Caroline, Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network (Princeton University Press, 2015).