My family and I are just back from visiting our daughter, who works in Uganda, with a two-day stop in Dubai, where there’s a change of flights en route from Boston to Entebbe. We chose these destinations for family reasons. But it’s significant that Emirates Airlines flies direct from Dubai to Uganda. Even though the United Arab Emirates is small, and these two countries lie far apart, the UAE is Uganda’s 4th-largest source of imports. Dubai, an “Alpha+ Global City,” is a hub in a network of financial and human capital for a vast hinterland that includes Uganda, where 84% of the population still depends on subsistence agriculture.

There is much to like in both places—and reasons to hope that their futures will be brighter. However, if the worst aspects of each state predominate, and if the world increasingly resembles this pair of nations, then the human future will be dystopian.

Two centuries ago, both the Buganda Kingdom north of Lake Victoria and the Sheikdom of Dubai were independent monarchies. If we assume that today’s basket of most desired goods (life expectancies above 70, individual freedom, security, etc.) define human development—a contested assumption—than both societies were poorly developed. But they had rich and complex cultures and social structures.

The British made both kingdoms into dependencies and then subsumed Buganda within a full-fledged colony. The period of colonialism must have been experienced as traumatic in both countries. There were important differences. For instance, most Ugandans–but virtually no Emiratis–converted to Christianity. But they also shared some experiences, such as in-migration from South Asia. (Indians and Pakistanis now far outnumber Arabs in Dubai.) Police departments, accounting firms, factories, and many other innovations that we might label “modern” or “Western” arrived in both places with the British.

They gained independence within ten years of each other, but their economic trajectories have split. Dubai, a city-state entrepôt on one of the world’s busiest shipping lanes, has become the 9th-wealthiest nation in the world, with a per capita GDP of nearly $70k. Uganda, a land-locked agricultural nation of 38 million, ranks 163 out of 188 countries on the Human Development Index and has a per capita annual GDP of $572 and a median individual income (my favorite summary statistic) of $2.50 per day. By definition, that means that half of Ugandans live on less than that much–at least as far as a cash economy is concerned–and one in five live below the poverty line of $1.90 per day.

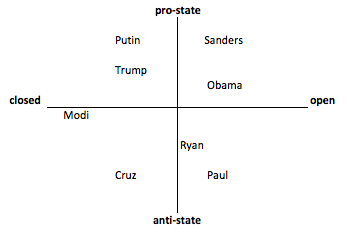

Their political trajectories have also split. Dubai has been a stable absolute monarchy within the federal structure of the United Arab Emirates. Political rights are nonexistent; there is no legitimate public sphere, in the sense of a zone where citizens freely form public opinion and influence the state. The Ruler may choose to consult, but he decides. Most residents are not citizens in any sense; about 90% percent are expatriates.

Albert O. Hirschman argued that two strategies are valuable when you don’t like how things are going: exit or voice. In Dubai, political voice is irrelevant or even illegal. But exit (along with entrance somewhere else) is prevalent. People shape Dubai by moving themselves and their assets there or away, whether they are construction or domestic workers from India or the Philippines or bankers or real estate developers from wealthy nations. With the exception of the most exploited workers, they can leave if they are dissatisfied. This means that Dubai has been created by its residents, not by the Ruler. It’s the residents who have thrust astounding numbers of postmodernist skyscrapers out of the desert or have withdrawn their capital when dissatisfied. But their influence is entirely individual and apolitical.

Uganda, meanwhile, has had a tumultuous history, with only three presidents (although four regimes) so far since independence, and still no peaceful transfer of power. We visited the underground cells behind Idi Amin’s former presidential palace where thousands were tortured and killed by electrocution; no one left those chambers alive. I don’t think I am naive about the limitations of the current democracy, as Yoweri Mouseveni spends his 31st year in the presidency. Yet Uganda is a democratic republic. The people govern through representative institutions, albeit with several dubious elections since 2001. The newspapers call Ugandans “citizens,” respecting them as the people who ultimately govern the republic and implicitly holding them responsible for doing so. (I think respect and responsibility are what define a republican form of government.)

Three democracy indices from V-Dem (not available for UAE)

The Ugandan press is vibrant and competitive. The standard journalistic style is a bit more stenographic than what we are accustomed to in the US. Many articles basically report what someone said, in the same order that he or she said it. But the perspectives captured in these stories are diverse and often sharply critical. There is a public sphere, even if the state is somewhat unresponsive to it.

If voice is more evident in Uganda than in Dubai, exit is rarer. Few Ugandans can afford to or want to leave, although remittances from emigrants are rapidly growing. The largest migration of people consists of refugees into the country from South Sudan; they lack both exit and voice.

In Dubai, the global consumer brands are pervasive, including the Trump brand, now attached to a huge new golf course. There is a preserved old qu arter that represents traditional Emirati culture, but it is probably smaller than one Bulgari ad on the side of one high-rise office building. We saw at least four billboards for completely different products that used the same format: a White woman in fashionable Western clothes and an Emirati man in a traditional white dishdosh and headscarf are beaming at the same consumer good. Even though about 70% of the residents are Asians, rich Westerners and Arabs are the normative consumers.

arter that represents traditional Emirati culture, but it is probably smaller than one Bulgari ad on the side of one high-rise office building. We saw at least four billboards for completely different products that used the same format: a White woman in fashionable Western clothes and an Emirati man in a traditional white dishdosh and headscarf are beaming at the same consumer good. Even though about 70% of the residents are Asians, rich Westerners and Arabs are the normative consumers.

In Uganda, despite a few ads for Coca-Cola and Pepsi, the global brands are rare. Almost all stores are one-story brick structures with a raised front wall that can display messages above the door. By my count, about 30% of the stores in the cities and along the paved intercity roads (but fewer on dirt back roads) display painted advertisements for a handful of local brands, mostly telecom service-providers, construction materials, and detergents. Another notable form of advertising consists of new mosques, ubiquitous next to the roads in this overwhelmingly Christian country, thanks to funding from Turkish and other Middle Eastern sources. Finally, one often sees the logos of aid agencies: national, multilateral, or nongovernmental. In one national park, a sign announced that the signage had been given by the “people of the United States” through USAID. Paying for the signs that carry our national logo seems a way to maximize the ratio of branding to actual benefit.

handful of local brands, mostly telecom service-providers, construction materials, and detergents. Another notable form of advertising consists of new mosques, ubiquitous next to the roads in this overwhelmingly Christian country, thanks to funding from Turkish and other Middle Eastern sources. Finally, one often sees the logos of aid agencies: national, multilateral, or nongovernmental. In one national park, a sign announced that the signage had been given by the “people of the United States” through USAID. Paying for the signs that carry our national logo seems a way to maximize the ratio of branding to actual benefit.

Language often offers insights into culture. I’m sure that individuals in each country have unique relationships to the languages they speak, but I’ll risk some generalizations about English in Uganda and in the UAE. Ugandan (or East African) English is a branch of the language, like the Queen’s English or my own. It is mutually intelligible with American English, yet highly distinctive, full of terms for local foods and activities, loan-words from Swahili, and idioms and rhythms that make it a vehicle for expressing a particular culture. You could learn to speak Ugandan English, and that would be a linguistic attainment, an addition to your repertoire.

The English of the UAE sounds to me like what one learns in a second-language course in a business college. It is error-prone but functional, jargon-filled, strictly pragmatic. It might offer possibilities for creativity and insight—but I doubt it. I’m guessing that most residents experience cultural depth and aesthetic satisfaction in their native tongues. In Joseph O’Neill’s wonderful novel set in Dubai, The Dog, the narrator says, “I have a real soft spot for the habitual accent of Arab speakers of good English, in whose mouths the language, imbued with grave trills, can seem weighted with the sagacity of the East. (See Alec Guinness in Lawrence of Arabia.)” That may be true, but only 12% of the UAE’s residents are Emirati, and not all of those speak good English. Purely functional English–plus math–is the code of business, and business is the culture that counts in Dubai.

Looking toward the future, one can imagine that Dubai adds political liberties and public deliberation to its market freedoms, and Uganda not only honors the true spirit of its republican constitution but also develops sufficiently so that all its people attain the core human capabilities. That would be a better world. To be even more utopian, we might hope that the relationships among Uganda, Dubai, and the inevitable third corner of the triangle–the OECD nations–becomes genuinely just, not just in the sense that human circumstances converge but also that the people of Uganda can make real claims on the people of Dubai or New York.

One can also imagine that Dubai continues to prosper without political freedom, much as Shanghai also does today. Absolute monarchies seem quaint, but arguably the real players in Dubai are the big corporate investors, and corporations are not democracies. Their influence could grow, not only in Dubai but in all the Global Cities. Indeed, as the world gets hotter, dryer, more postmodern, higher-tech, more racially intermingled, yet more culturally homogeneous, one could imagine that all the cities that dominate the global economy will look like Dubai today. Already, the man whose portrait hangs in every federal office building in the USA also has his name on the huge billboards for Dubai’s newest golf course.

Meanwhile, Uganda faces rapid population growth, a median age of 15, a worsening climate, unstable neighbors in several directions, and the risk of political instability once Mouseveni finally retires. One could imagine that Uganda will look much as it does today, only poorer and more violent, and that many other nations will look more like it. That is the dystopian future that haunts us.