I argued in a recent post that libertarians, social democrats, American liberals, and most US Constitutional scholars share a sharp distinction between the state and the private sector–but this distinction does not reflect our actual experience of the social world.

One result is a certain way of thinking about freedoms of speech, the press, assembly, religion, and petition (the Five Freedoms of the First Amendment, which are also important rights in other democracies).

A typical first step is to identify which institutions are public or state bodies. They should be prevented from interfering with other people’s speech and assembly, and they should be constrained from expressing themselves in certain ways. For instance, the US government may not express support for any specific religion, although anyone else in the society may.

The next step is to safeguard the freedoms of non-public groups, including their freedom to discriminate and exclude. For instance, the Catholic Church is not required to ordain non-Catholics (or women) as priests. Such requirements would violate its freedom of assembly and religion.

Then we face two recurrent debates. One is whether various private associations (universities, web platforms) should act like states, even though perhaps they don’t have to under the Constitution. For instance, should a private university accord its students untrammeled freedom of speech? The other debate is whether hybrid institutions (state universities, political parties, public broadcasting services) are more state or private. Do they have First Amendment rights or must they safeguard others’ rights, or both?

The debate about the role of speech in our democracy thus centers on questions like comment-moderation, inviting or disinviting speakers, speech codes, hate speech–all of which have a legalistic flavor. The question is who has a right to say what, where.

If I actually had any influence, I would not seek to upset the apple cart of American constitutional thought. The categories that we have drawn (public/private, freedom/restriction) reflect some accumulated wisdom and offer some practical advantages. I would give a Burkean justification for how we employ the First Amendment: it is how we have learned to operate.

But the distinction between state and private sphere is at odds with the reality of how institutions work. They are almost all hybrids, partly public and partly private, exercising power but also allowing voice, including some and excluding others.

So what if we started instead with a population of people–individual human beings–who come together in a wide range of organizational forms to define, discuss, and address problems? I think these are the important points for them to consider in relation to freedom of speech:

- They need structured, reflective discussions that encompass a diversity of views and respond to good reasons or insights, not to power. They don’t need consensus, but they must continuously learn from others.

- Good discussions take institutional forms, from op-ed pages to seminars to town meetings. All institutions have rules, norms, resources, and incentives. Incentives are necessary because participation in a discussion has costs. It takes time and energy to discuss, and the conversation may cause discomfort. Individuals don’t have to participate. Successful institutions for communication or discussion find ways to lure people in. A classic example was the package of the local daily newspaper: comics and sports to encourage subscriptions, and a sober front page to direct your attention to serious matters. The demise of this business model is an important example of what we should worry about.

- Any good discussion is a common-pool resource. It requires voluntary contributions, it serves all who participate, but it is easy for individuals to ruin. There are principles for the management of fragile common-pool resources.

- On the list of principles you will not find a requirement to discuss all the rules and incentives all the time. On the contrary, groups must economize on disagreement. They can’t handle too much of it. And any discussion assumes a prior solution to a problem of collective action. People didn’t automatically want to show up and talk; they were drawn in. This means that discussions generally rely on founders, small groups of leaders, or past generations of participants. We don’t make our own discussions; we join them. The structure of the institution constrains the discussions that take place within it, but there is no such thing as an unstructured discussion.

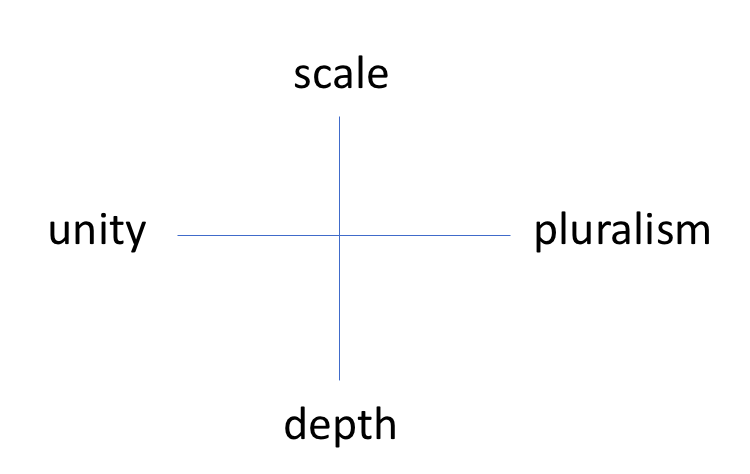

- Given the fragility of institutions for discussion and the importance of building institutions that match various needs and interests, they must be plural. We need lots of overlapping but heterogeneous forums–face-to-face, online, big, intimate, ideologically coherent and ideologically diverse. Each one will set rules for what speech it allows, but the rules will also determine who participates, the costs and benefits of participation, the scale, and a range of other issues. No set of rules is ideal; it’s the whole ecosystem that matters.

None of this is original. It reflects well-developed lines of argument from the sociology of communication and other fields. But it is an alternative to the US discourse of free speech, which is all about rights and restrictions. It focuses instead on the design of multiple institutions for communication–their resources, boundaries, rules, and norms.