With a newly elected President and the most fragmented Parliament in its history, Brazilian politics are likely headed for gridlock. Lottery could well be the solution.

Tiago Peixoto and Guilherme Lessa

For many Brazilians who recently cast their ballots to elect a new President, the choice was between the unacceptable and the scandalous. Mr. Bolsonaro, the winning candidate, received 39.3% of votes, while abstentions, null and blank votes accounted for 28.5%. A record 7.4% of votes were null, the largest percentage since Brazil’s transition to democracy in the late 1980’s. Considering that voting is compulsory in Brazil, these figures signal a deep and persistent disbelief in democracy as a means to improve the life of the average citizen. When asked about her preferred candidate at the polling station, it would not be unthinkable for a voter to respond “I’d rather randomly pick any Brazilian to run the country.”

The idea may seem absurd, or a symptom of the ideological schizophrenia that now ravages Brazil, where the two contenders for the highest office were diametrically opposed and their supporters’ main argument was “the other is worse.” Research conducted in the United States indicates that the electorate’s mistrust of their representatives is far from being a Brazilian idiosyncrasy: 43% of American voters state they would trust a group of people randomly selected through a lottery more than they trust elected members of the Executive or Legislative.

Many political scientists view this as a symptom of a global crisis of representation, a growing distance between representatives and the represented, both part of a machine mediated by parties that are disconnected from everyday life and often involved in corruption scandals. While political parties are suffering decreasing membership, political campaigns are increasingly dependent on large donations and mass media campaigns – all of which can be done without the engagement of everyday citizens. The disconnect between citizens and their representatives has driven the international success of candidates who claim to be political outsiders (even if they are not) and private sector meritocrats.

Representative democracy has always suffered from an inherent contradiction: electoral processes do not generate representative results. Think of the teacher who asks her students who wants to be the class representative. Only one or two students raise their hand. To be a representative does not require broad knowledge of the reality of the represented but, rather, an extroverted and sociable personality which, ultimately, lends itself to the role to be played. In the case of elections, the availability of time and money for campaigning, as well as support from the party machinery, are also predicting factors in who gets to run and, most importantly, who gets to win.

The bias generated by electoral processes can take several forms, but is particularly visible in terms of gender, race and income. For instance, despite high turnover in the Brazilian Legislative, the numbers remain disheartening. While half of the population is female, their participation in the House of Representatives stands at a meager 15%. Similarly, 75% of House members identify as white, compared to 44% of the Brazilian population. The mismatch is not unique to Brazil. As reported by Nicholas Carnes in his recent book The Cash Ceiling, in the United States, while millionaires represent only three percent of the American population, they are a majority in Congress. While working-class people make up half of US citizens, they only account for two percent of members of Congress.

The denial of politics as a symptom of this disconnect demonstrates the extent to which inclusiveness in politics matters, bringing about some worrisome consequences. Heroic exceptions aside, the election of new representatives generally fails to alter the propensity of the electoral machine to reproduce its own logic. The Brazilian electoral system, like that of other modern democracies, continues to produce legislative bodies that fail to represent the diversity of their electorate. Changing politicians does not necessarily imply changing politics.

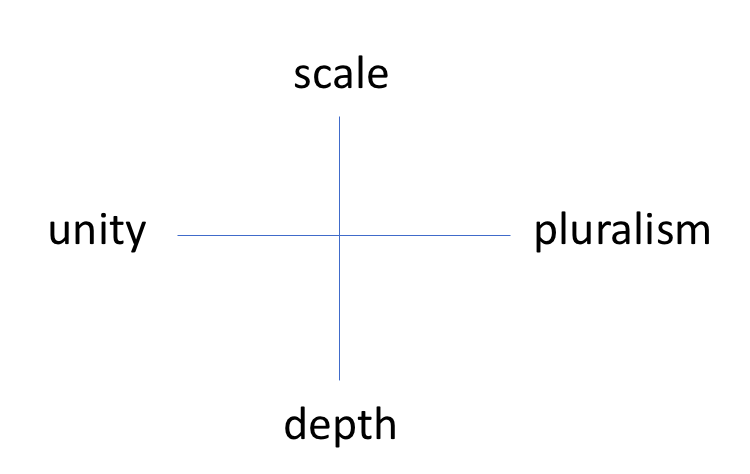

Fixing this imbalance between the electorate and the elected is a complex matter with which many scholars of democracy have grappled. An increasingly popular proposal among political scientists is the use of lottery as a complementary means to select Legislative representatives. Proponents of this approach describe several advantages, of which three are worth highlighting. First, a body of representatives selected by lottery would be more representative of the population as a whole, resulting in agendas and policies that are more closely aligned with societal concerns. Second, the influence of money in campaigning – a constant source of scandal and corruption – would be eliminated. Finally, and in line with well-established research in the field of decision-making, a more diverse legislative body would be collectively smarter, generating decisions that could maximize the public good.

But how would this work in practice?

“Let’s hold a lottery!”, says the spokesperson for today’s miracle solution. Lottery, after all, does have its precedents in democracy’s formative history. For over a century in classical Athens, randomly selected citizens were responsible for important advances in legislation and public policy. Similarly, at its height, the Republic of Florence used lottery to allocate some of the most important positions in the Executive, Legislative and Judiciary. Today, several countries use juries composed of randomly selected citizens as a means to ensure impartiality and efficacy within the Judiciary.

Globally, we see hundreds of inspiring experiences in which randomly selected citizens deliberate on issues of public interest: in Ireland and Mongolia to guide constitutional reforms; in Canada to inform changes in electoral legislation; in Australia to develop public budgets; and in the United States to support citizens’ legislative initiatives.

Naturally, such a complex and somewhat unexpected proposal brings about a challenging question: how can it be implemented in a way that results in a more representative Legislative? Changing the rules of the game, as we all know, is not a trivial task. Political reform, even if thoroughly thought through, still depends on the approval of those who benefit the most from the status quo.

The proponents of lottery selection rarely advocate for the direct substitution of members of parliament by randomly selected citizens. Pragmatically, they usually call for the implementation of intermediary strategies, such as the use of citizens’ panels as complementary decision-making processes.

So why not try it?

It is an established fact that Mr. Bolsonaro will be faced with one of the most fragmented congresses in Brazilian history. While his initial popularity may allow the president-elect to pass reforms in the first few months of his mandate, decision paralysis and political gridlock seem inevitable in years to come.What risk, then, would a panel of randomly selected citizens with a voice and a vote in congressional committees dealing with specific policies such as environment and education pose? Like a jury, such a panel would dedicate its time to understanding the facts relating to the subject at hand, listen to different positions, formulate amendments and potentially cast votes on the most divisive issues. It would represent a microcosm of Brazilian public opinion in an environment that is informed, egalitarian and civilized. Although unlikely, such a reform could be the first step towards strengthening the (increasingly weak) link between representatives and the represented.

*Article translated and adapted from original, published in Revista E, ed. 2400, October 2018.