If you want a more deliberative society–one in which diverse people discuss and learn before (and while) they act politically–you’re not going to accomplish it simply by promoting deliberation. Too many people are understandably motivated by specific agendas, and too many resources are spent to promote specific goals, for a deliberative strategy to work on its own.

But we do have social movements, and they could fuel deliberation. At first glance, they don’t seem promising, because they tend to recruit people who share specific goals and then make demands on target authorities. They do not seem likely to encourage discussion among people who disagree. Charles Tilly, a major theorist of social movements, argued that movements need WUNC–worthiness, unity, numbers, and commitment–to succeed (Tilly 2004). A large group of people who demonstrate unity do not seem to be deliberating.

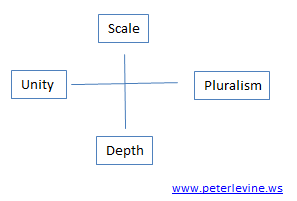

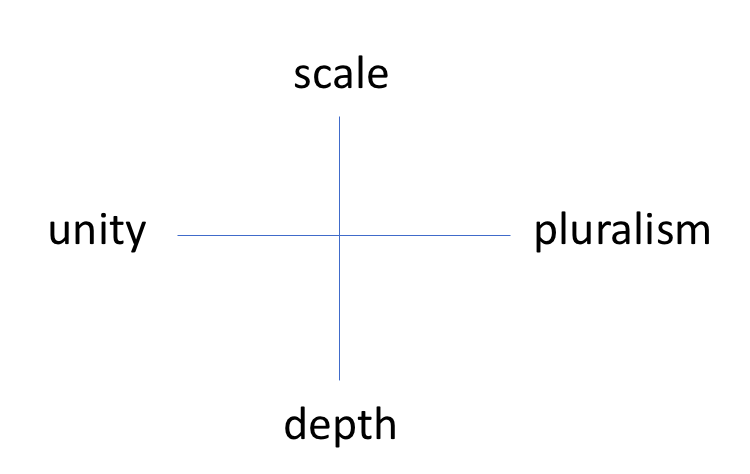

However, the research increasingly suggests that social movements are more likely to succeed if they are internally diverse and good at promoting a free and rich internal conversation. I have cited Erica Chenoweth & Maria Stephan (2011) and Marshall Ganz (2010) to this effect. My own model is SPUD: movements need scale (lots of people), pluralism (diversity of identities and views), unity (shared objectives and tactics), and depth (growth and learning for the participants). Deliberation is relevant because it takes talk to combine scale with depth and pluralism with unity.

New support comes from Wouters (2018). He has shown Belgian and American samples media clips of protests that demonstrate WUNC and that are experimentally altered to show either more or less diversity.

Diversity deals with the heterogeneity of a demonstration’s composition and thus with variation in descriptive characteristics of participants (participation of the young and the elderly; employers and employees; the rich and the poor). Whereas unity deals with the extent to which a group is on the same page and a solid bloc, diversity focuses on a march’s composition. Whereas numbers appeal through an increase in quantity, diversity boosts attractiveness through an increase in quality (various types of participants). Diversity breeds public support, I argue, because observers are presented with more opportunities to identify and because it signals observers that the movement and its grievance engage all citizens. Non-diverse crowds create the impression that the protest serves narrow self-interests, limiting potential identification. In sum, I expect more diverse protesters to facilitate identification and to trigger more supportive reactions.

His finding is that diversity improves audiences’ responses to the protests. He has coined the term dWUNC, “diverse WUNC,” and sees it as an ingredient of success.

Wouters argues that protests are more appealing when members of the audience can see individuals like them among the protesters. They are more likely to see people like themselves if the movement is diverse. He notes that Black Lives Matter protests became more appealing to white viewers if they included some white participants, but black viewers’ opinions did not change.

Wouters’ findings are troubling because demographically homogeneous groups also have value. Oppressed people have a right (and sometimes have good reasons) to act separately, without demonstrating that they have “diverse” support. However, if Wouters is correct, then it’s worth at least considering the cost of fielding a homogeneous group.

I would add that a movement that consistently puts diverse people onto the streets will have to promote internal deliberation to keep those people unified. If this is correct, then a strategy for making society more deliberative is to encourage social movements to maximize their internal diversity. They should do so to make themselves appealing, but as a major side effect, they will promote deliberation.

I make this argument in Levine 2018, but without citing Wouters 2018, which appeared too recently. Here is my PowerPoint on the topic:

Citations

- Erica Chenoweth & Maria Stephan, Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict (Columbia Studies in Terrorism and Irregular Warfare, 2011)

- Marshall Ganz, Why David Sometimes Wins: Leadership, Organization, and Strategy in the California Farm Worker Movement (New York: Oxford University Press, 2010), pp. 17-18.

- Peter Levine, “Habermas with a Whiff of Tear Gas: Nonviolent Campaigns and Deliberation in an Era of Authoritarianism,” Journal of Public Deliberation, in press

- Ruud Wouters; “The Persuasive Power of Protest. How Protest wins Public Support,” Social Forces, soy110, https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soy110 (03 November 2018)

- Charles Tilly, Social Movements: 1768-2004 (Boulder/London: Paradigm, 2004)

- Support, Social Forces, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1093/sf/soy110

See also: we need SPUD (scale, pluralism, unity, depth); closing remarks at the Bridge Alliance summit; Why Civil Resistance Works; tools for the #resistance; and so, you want to strengthen democracy?