My remarks at a conference entitled “Empathy …. or Ways of Caring,” Harvard Department of Romance Languages and Literatures, March 15, 2019. (Apologies for some cutting and pasting from previous posts.)

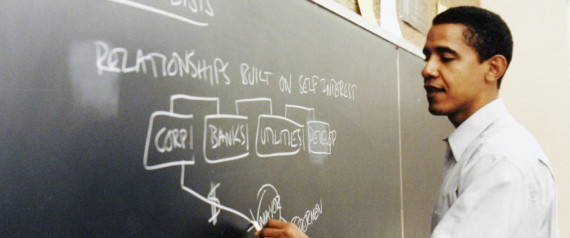

Doris Sommer mentioned that Barack Obama popularized the notion of an “empathy deficit.” In a 2004 interview with Oprah Winfrey, while he was still a State Senator, Obama said:

I often say we’ve got a budget deficit that’s important, we’ve got a trade deficit that’s critical, but what I worry about most is our empathy deficit. When I speak to students, I tell them that one of the most important things we can do is to look through somebody else’s eyes. People like bin Laden are missing that sense of empathy. That’s why they can think of the people in the World Trade Center as abstractions. They can just crash a plane into them and not even consider, “How would I feel if my child were in there?”

Here Obama links empathy to moral judgment. In a 2006 commencement address, he also implies that the level of empathy in a society as a whole is a precondition of social justice. Our “empathy deficit” explains why we accept that “Americans … sleep in the streets and beg for food,” that “inner-city children …. are trapped in dilapidated schools,” and that “innocent people [are] being slaughtered and expelled from their homes half a world away .”[2]

To suggest that this argument is problematic, I would quote then-President Obama in Jerusalem on March 21, 2013:

I — I’m going off script here for a second, but before I — before I came here, I — I met with a — a group of young Palestinians from the age of 15 to 22. And talking to them, they weren’t that different from my daughters. They weren’t that different from your daughters or sons.

I honestly believe that if — if any Israeli parent sat down with those kids, they’d say, I want these kids to succeed. (Applause.) I want them to prosper. I want them to have opportunities just like my kids do. (Applause.) I believe that’s what Israeli parents would want for these kids if they had a chance to listen to them and talk to them. (Cheers, applause.) I believe that. (Cheers, applause.)

It is not so much the speech as the applause that I find problematic, because I believe that the Israeli electorate supports policies that are unjust, and their political behavior is compatible with a fair amount of actual empathy.

The word “empathy” is a modern coinage. It is not attested before 1895, and it gained its current meaning only in 1946. Many wise people have thought about moral psychology and justice without using this word at all, so we should consider whether it does us any good.*

I’d posit the following definitions:

- Empathy: Feeling a similar emotion in response to someone else’s emotional state. Your friend is mad at her boss because he treated her unfairly. That makes you mad at her boss. Your anger is probably different in texture and intensity from hers, but it’s the same in kind, an imperfect reproduction of her mental state.

- Sympathy: Feeling a supportive emotion in response to someone else’s emotional state that is not the same as that person’s original emotion. She is mad at her boss, so you become sorry for her, or committed to fairness, or sad about the state of the world, or nostalgic for better times–but not angry at her boss. Then you are sympathetic. (NB You can be both sympathetic and empathetic if you feel several emotions.)

- Compassion: A species of the genus sympathy. Another person’s negative emotion causes you to have a specific supportive feeling that is not the same as her emotion: you sincerely wish that her distress would end without blaming her for it.

- Justice: A situation or decision characterized by fairness, goodness, rightness, etc. (These are contestable ideas and may be in tension with each other.) The English word “just”–like dikaios in classical Greek–can be applied either to a situation or to a person who cares and aims for justice.

There is an old and rich debate about which character traits and subjective states are best suited to pursuing justice. One answer is that you should be a just person, one who tries to decide what is fair or best for all (all things considered), who desires that outcome, and who works to pursue it.

A different response is that we are not well suited to defining and pursuing justice itself. We lack the cognitive and motivational qualities that would allow us to grasp justice and reliably act on it.

Justice is an abstract idea that takes the form of words: it is discursive. According to a mainstream view in contemporary moral psychology, we first form emotional opinions about concrete situations and then we select the ideas that will justify those opinions, post-hoc. Justice doesn’t guide us; it justifies and excuses us.**

In that case, it might be better to cultivate emotions, such as empathy, sympathy, compassion–or loyalty, aversion to harm, or commitment to specific rules–in order to deliver more just outcomes, all things considered.

In her remarks, Marina Amelina noted that developed countries built social welfare systems between ca. 1880 and 1970. That could because their publics became more empathetic. But it also be because less-wealthy people gained power and used it to protect themselves. Equal power plus self-interest might generate justice more reliably than empathy. John Rawls famously modeled justice as the decisions that self-interested parties would make if they were rendered perfectly equal by a Veil of Ignorance that blocked them from knowing their own situations. In the real world, we can approximate the Veil of Ignorance by assuring that everyone has equal rights and powers. This is a clear alternative to the view that justice should be built on empathy.

Paul Bloom and others argue that empathy is particularly unreliable guide to justice, more likely to mislead than to inform. For instance, Donald Trump can make people feel empathy for a small number of individuals whose families were allegedly victimized by undocumented aliens, and then use that emotion to build support for deporting millions of people who have harmed no one. A famous example is Edmund Burke’s outrage at the mistreatment of Marie Antoinette, which obscured any concern for the countless people tortured, executed, or “disappeared” by the ancien regime that she represented. (By the way, I respect Burke–and I don’t think it was fair or smart to execute the Queen–but this passage is still a good example of misplaced empathy.)

Empathy can also substitute for justice, as the transcript from Jerusalem that I quoted earlier suggests. You congratulate yourself for feeling some version of a suffering person’s emotion and excuse yourself from fixing the problem.

Compassion may be better than empathy. Instead of feeling the same emotion as the other person, you feel a combination of beneficence and equanimity that may be a more reliable guide to acting well. But it’s possible that compassion only clears the deck for reasoning about what you should actually do.

Other candidates for emotional states that might be more reliable than empathy include solidarity, responsiveness, openness, and intellectual humility.

For its part, justice can be emotional. You can feel a powerful urge to make the world more just. That is helpful insofar as the feeling motivates you and insofar as people obtain genuine insights from our emotions; but it is dangerous because the emotion of desiring justice can be misplaced. You can feel great about improving the world when you are actually harming it.

In the end, I think we must wrestle with these questions:

- Can we human beings reason explicitly about justice in ways that improve upon our strictly affective reactions to particular situations? Can we put into words what is good or fair, and why, and make ourselves accountable for that position? Or is this always special-pleading, mere rhetorical justification for what we have already decided based on our emotions?

- Does an improvement in social justice indicate an improvement in empathy?

- If we should cultivate an emotional stance toward others as a buttress of—or an alternative to—justice, should that stance be empathy, or rather compassion, responsiveness, solidarity, humility, or something else?

*Buddhism is perhaps most widely associated with the virtue that Obama calls “empathy”—in his terms, “the ability to put ourselves in someone else’s shoes; to see the world through those who are different from us” (Northwestern Commencement speech). But Emily McRae notes that “empathy” has no direct translation in Sanskrit or other languages that have been used to express the Indo-Tibetan Buddhist tradition. Key words from that tradition are better translated as “compassion” and “sympathetic joy.” McRae derives a theory of empathy from Buddhist texts, but she focuses on phrases like “exchanging self and other” rather than any single word that corresponds to “empathy.” McRae, “Empathy, Compassion, and ‘Exchanging Self and Other’ in Indo-Tibetan Buddhist Ethics” in Heidi Maibom , ed., The Handbook of Philosophy of Empathy (Routledge, 2017).

**Jonathan Haidt, The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion(New York: Vintage, 2012), pp. 27-51; Ann Swidler, Talk of Love: How Culture Matters (Chicago: University of Chicago Press. 2001); pp. 147-8; Leslie Paul Thiele, The Heart of Judgment: Practical Wisdom, Neuroscience, and Narrative Cambridge University Press, 2006) and Jesse Graham, Brian A. Nosek, Brian A., Jonathan Haidt, Ravi Iyer, Spassena Koleva, & Peter H. Ditto, “Mapping the Moral Domain. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, vol. 101, no. 2 (2011)., p. 368)

See also: empathy, sympathy, compassion, justice; empathy: good or bad?; “Empathy” is a new word. Do we need it?; how to think about other people’s interests: Rawls, Buddhism, and empathy