National attention has turned to political debates and conflicts at one flagship Land Grant state university and one Ivy League. Mizzou and Yale exemplify the whole higher education system, which is a political flashpoint–for good reasons.

On one hand, universities are designed to stand somewhat aside from the political/economic system, to be independent of the usual power structures, and to supply, teach, and encourage critical analysis. On the other hand, they are absolutely pivotal to maintaining the political/economic system that exists, with all of its flaws as well as its virtues.

Racism is the main topic of the current activism. I fully concur with the importance of racial injustice on campuses. (See Jelani Cobb‘s summary, although Conor Friedersdorf‘s response is also valuable and not diametrically opposed.)

If you want a detailed, sophisticated, critical view of racism in America, higher education is one important place to find it. Many faculty share the critical diagnosis. And the most prestigious universities supply some of the most sophisticated and trenchant criticism.

At the same time, only 4 percent of full professors in America are Black. Young White adults are twice as likely to have a college degree as young African Americans (40% versus 20%), due to an accumulating series of racial gaps in k12 promotion and retention, high school graduation, college admission and retention, and on-time graduation. Their lower college graduation rates are one indication of a generally less supportive and satisfying educational experience for students of color. Given the demographics of faculty and students, the culturally dominant group is almost always White, and they have the whole symbolic heritage of the universities behind them. Finally, these institutions exist in blatantly unjust larger communities. Mizzou is the flagship university of the state that encompasses Ferguson. Yale is in the heart of New Haven, where the NAACP reports that 25% of Black families live below the poverty line, 18.9% of Black children have asthma, and no public school sees more than 28% of its graduates achieve a college degree.

Racial issues are thus unavoidable and supply telling examples of the contradictions built into higher education. But the contradictions extend further. For instance, if you want a trenchant and sophisticated critique of Wall Street, an excellent place to look is in the classrooms and journals of the finest American universities. One stream of critique is economic, but you can also find critical views of the culture, psychology, and even the aesthetics and spirituality of 21st century capitalism. An institution like Mizzou or Yale is designed to be safe from the incentives and pressures that dominate contemporary capitalism so that it can provide an independent view; hence the rules that govern tenure, academic freedom, etc.

Yet these institutions produce the people who actually take over and profit from contemporary global capitalism. The financial services industry employs more members of the Yale class of 2013 (14.8%) than any other other field. Consulting employs another 11.6% of that class. Many more Yalies apply to but don’t get Wall Street jobs right away. And of the 18.2% who go straight to graduate school, many are heading to finance via law school or business school. From a different perspective, we can say that Wall Street is dominated by graduates of institutions like Yale.

So these colleges select the global economic elite, disproportionately choosing the children of the current elite. They expose them to four years of critique of the global economic system–some of it very gentle and subtle, and some fairly blatant. Students see implicit alternatives to contemporary capitalism when they study Dante or Buddha in a seminar room, and they get direct criticisms in social science and philosophy classes. These experiences probably sharpen their minds and skills before they proceed in disproportionate numbers to take over the dominant political/economic institutions of the world and to fund the universities that chose and prepared them so well.

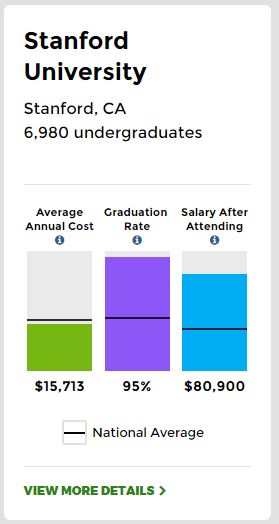

All kinds of odd practices and situations arise. For instance, Yale has $2.4 million of endowment per student, sufficient to generate about $112,000 of annual revenue per student. Given Yale’s faculty/student ratio of 6.1:1, that means the university gets about $683,000 per professor per year from its endowment funds. Yet it charges the students a sticker price of more than $50,000 and constantly solicits its alumni for donations to make enrollment affordable. The institution presents itself as a tax-deductible nonprofit philanthropy devoted to light and truth, yet it is also a corporation with $23.9 billion in the bank. Many of its faculty see themselves as critics of the status quo, yet they work in an institution that replicates it.

I love these places. They have been very good to me–Yale more than any other institution. They have broadened my mind and given me whatever skills and passions I have for analyzing social justice. They create zones of debate and critique that are freer and more vibrant than most other sectors of our society, and they encompass more diversity than most of our neighborhoods and work sites. To the extent that we have any upward mobility, they provide some of the upward paths. They permit and even encourage the criticism that is directed at themselves. At the same time, they are pillars of social injustice. No wonder they stand in the crosshairs today.