I’ll be overseas, mostly in Uganda, and mostly offline until Feb. 25. I’ll resume posting after then.

Monthly Archives: February 2017

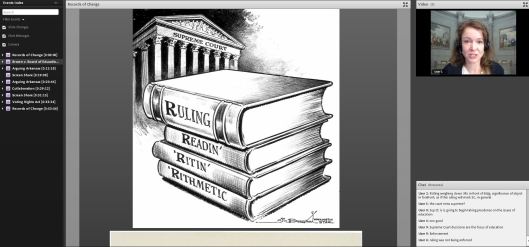

Records of Change: NARA Civil Rights Movement Webinar is Now Available!

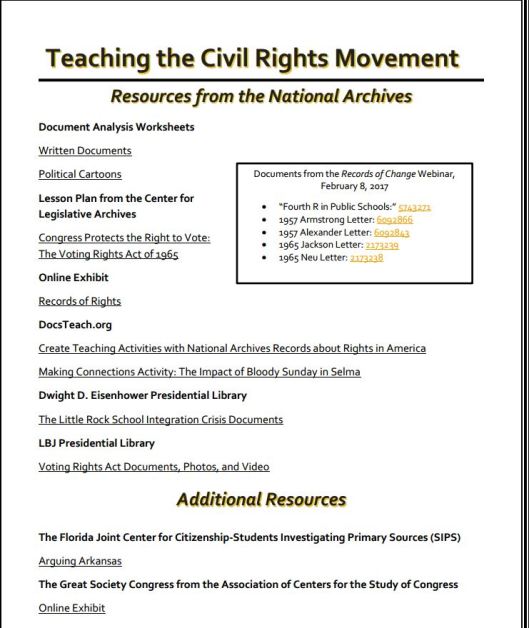

So, good news everyone! The recent webinar we co-hosted with the National Archives is now available. You can access the webinar at this link. In this well-attended discussion, Kathleen Munn of NARA discusses primary source tools and resources that can be used to approach the Civil Rights within classroom discussion.

All of the resources used and referenced in the presentation are available here: recordsofchangewebinarresources-1 . Please note that the PDF contains embedded hyperlinks, so you will need to be sure to download it!

We do hope you enjoy the webinar, and we are grateful for our partners at the National Archives. They always do such great work!

Lessons on Turning Deliberation into Action from Alabama

The David Mathews Center – an NCDD member org – recently completed a great deliberative process focused on helping Alabama communities take action together to improve their town, and we think many in our network could learn a thing or two from it, so we’re sharing about it here. The DMC team wrote an insightful piece on their three-stage process of moving the town of Cullman from talk to collaborative action, and we encourage you to read it below or find the original version on their blog here.

What’s Next, Cullman? Pilot Program Wraps Up

The DMC recently wrapped up its pilot forum series for What’s Next, Alabama? in the city of Cullman, with promising results.

The DMC recently wrapped up its pilot forum series for What’s Next, Alabama? in the city of Cullman, with promising results.

What’s Next, Alabama? (WNAL) is shaping up to be the Mathew Center’s largest programmatic undertaking to date. WNAL is a part of the DMC’s flagship program, Alabama Issues Forums (AIF), and will feature three deliberative forums in each community, focused broadly on issues of community, economic, and workforce development.

The first forum will ask, “Where are we now?” How did your community get to where it is today? What has been working well, and what hasn’t? What are the assets already have at your disposal? The second forum will ask, “Where do we want to go?” What would you like to change about your community? What would you live to preserve? What issue(s) would you like to tackle? What are your priorities? The third forum will ask, “How do we get there?” Using the resources you have, what is most doable? What are the next steps? How can you move from talk to action? Partnering with local conveners including the LINK of Cullman County and the Alabama Cooperative Extension System, we were able to launch What’s Next, Cullman? as a pilot program and our first WNAL community.

The first forum gave the community an opportunity for deep reflection on the changes Cullman has seen through the years. Attendees crafted an exhaustive list of what they loved about their community and what assets they could leverage, before moving on to discuss the challenges that face their community. The second forum allowed the community to take the challenges identified, and craft them into opportunities for action. Of all the issued discussed, two rose to the surface, and were identified as priorities for the community: developing “soft skills” in the community’s young people, and expanding options for public transportation.

In the final forum, attendees really prioritized the lack of public transportation options, and began to make a plan to move toward action. After much deliberation, the community came to an ingenious, asset-based plan for creating more options for transportation: tapping into the vast network of churches in the community, they could create an inter-congregational ride share program. With each church operating on a neighborhood-wide level, and with the cooperation of the many other churches in the city, even the tiniest effort by an individual church could have a huge impact, when combined with the efforts of other churches.

This is a prime example of how ordinary citizens, in no official “position of power” are able to leverage their inherent power and expertise as members of a community in order to take a fresh look at the assets of their community, and build a local solution to address a local challenge. This is the kind of locally-grown civic action that the DMC hopes to cultivate with the WNAL forum series.

As we have worked towards launching this forum series, we are invariably heartened by the care and dedication exhibited by Alabamians for the place they live. We are incredibly grateful for our conveners in Cullman, and the community at large, for embracing us and giving us the opportunity to work with them. We are confident that as WNAL evolves, and more resources become available, the potential for Alabamians to build civic infrastructure in their own communities will increase exponentially.

You can find the original version of this David Mathews Center blog post at www.mathewscenter.org/wnal-cullman-pilot.

Ideals of Inclusion in Deliberation

The 23-page article, Ideals of Inclusion in Deliberation, was written by Christopher Karpowitz and Chad Raphael, and published in the Journal of Public Deliberation: Vol. 12: Iss. 2. In the article, Karpowitz and Raphael, build off of previous research they performed regarding inclusivity within democratic deliberation.

They propose four ideals of inclusion summarized in the abstract, “These principles of inclusion depend not only on the goals of a deliberation, but also on its level of empowerment in the political system, and its openness to all who want to participate. Holistic and open deliberations can most legitimately incorporate and decide for the people as a whole if they are open to all who want to participate and affirmatively recruit perspectives that would be underrepresented otherwise. Chicago Community Policing beat meetings offer an example. Holistic and restricted forums (such as the latter stages of some participatory budgeting processes) should recruit stratified random samples of the demos, but must also ensure that problems of tokenism are overcome by including a critical mass of the least powerful perspectives, so that their views can be aired and heard more fully and effectively. Forums that aim to improve relations between social sectors and peoples should provide open access for all who are affected by the issues (relational and open), if possible, or recruit a stratified random sample of all affected, when necessary (relational and restricted). In either case, proportional representation of the least advantaged perspectives is necessary. However, when deliberation focuses on relations between a disempowered group and the rest of society, or between unequal peoples, it is often most legitimate to over-sample the least powerful and even to create opportunities for the disempowered to deliberate among themselves so that their perspectives can be adequately represented in small and large group discussions. We illustrate this discussion with examples of atypical Deliberative Polls on Australia’s reconciliation with its indigenous community and the Roma ethnic minority in Europe.”

Read an excerpt of the article below and find the PDF available for download on the Journal of Public Deliberation site here.

From the article…

Tensions between equality and equity occur at every stage of public deliberation in civic forums, but perhaps nowhere more than with respect to the question of inclusion. Given that deliberative theory is premised on the idea of free and equal citizens exchanging reasons and making decisions together, an abiding concern from both critics and champions of deliberative approaches has centered around whether background inequalities harm disadvantaged groups at various points in the deliberative process (Young, 2000). Such harm may occur prior to any reasons being exchanged at all when inequalities shape who is able to show up to deliberate in the first place. As Gutmann and Thompson put it, “When power is distributed unequally and when money substantially affects who has access to the deliberative forum, the results of deliberation in practice are likely to reflect these inequalities, and therefore lead, in many cases, to unjust outcomes” (2004, p. 48).

A common response to such concerns has been to focus on the representativeness of the deliberating group, making sure that forums are a microcosm of some larger population, whether international, national, or local. One strategy for maximizing inclusion is to open the forum to all who want to participate, while making special efforts to recruit a critical mass of people who would likely be under-represented otherwise (Leighninger, 2012). A second approach, which some deliberative theorists prefer, involves using random sampling to create a deliberating body that looks like the larger group being sampled in as many ways as possible, while giving each member of a population an equal probability of being invited to participate (Barber, 1984; Carson & Martin, 1999; Fishkin, 2009; Gastil, 2008).

Either approach prompts a critical question: who or what exactly needs to be represented inclusively? Many theorists of deliberation have argued that all who are affected by a decision should be represented in discussions (e.g., Cohen, 1989; Dryzek, 2000; Habermas, 1996), while recognizing that in an increasingly interconnected world, it is difficult to draw boundaries around those who are and are not touched in some way by an issue or a decision about it (Fung, 2013; Goodin, 2008). Thus, a deliberation’s legitimacy depends, first, on the justifications for defining who is affected by the issues on the agenda (Karpowitz & Raphael, 2014). Assuming that one has defined those boundaries appropriately, it makes sense to think of the population of all affected by a decision as a collection of perspective bearers most relevant to the issue under deliberation.

What are perspectives and why should we focus on representing them inclusively? In deliberation, participants should be open to reconsidering their beliefs, values, interests, and policy preferences, none of which can be assumed to be simple expressions of their ascriptive characteristics (such as ethnicity, sex, income, or sexual orientation). A perspective involves a structural location in society, which can, of course, be closely connected to social identities of various kinds, but in emphasizing perspectives, we seek to avoid essentializing those identities. Perspectives exist prior to deliberation and enrich discussion as they endure during deliberation. Iris Marion Young (2000) defines perspectives as the accumulated “experience, history, and social knowledge” derived from individuals’ locations in social groups (p. 136). However, as Young makes clear, perspectives do not determine the content of any individual’s beliefs, interests, or opinions. One’s perspective consists, instead, “in a set of questions, kinds of experience, and assumptions with which reasoning begins, rather than the conclusion drawn” (p. 137). In this sense, African-Americans can be said to share a perspective on public life that stems from their common experience of being perceived as black in America. Public forums about racism, income, policing, and many other issues would obviously want to be inclusive and representative of African-Americans without assuming that all black participants will agree on a set of shared interests or values, much less public policies. Similarly, a forum on free speech in schools should aim to include and represent students, who share a similar structural location with respect to the issue, even though they will not necessarily agree with each other about the specific rules, boundaries, and policies that might be proposed in a given school (for further discussion of perspectives, see Karpowitz & Raphael, 2014).

Perspectives are critical to the question of inclusion because a given perspective cannot be easily adopted by someone whose life experiences have occurred in a different social location than that occupied by the holder of that perspective or who has not shared the same set of experiences, history, and social knowledge. Mansbridge argues, for example, that the “vicarious portrayal of the experience of others by those who have not themselves had those experiences is often not enough to promote effective deliberation” (1999, p. 635). Of course, empathy is an important potential outcome of deliberative exchange, but such empathy is less likely if those with a given set of life experiences and perspectives are not present in the discussion. For example, a deliberative forum about contemporary immigration policy would likely be incomplete if it did not include the perspectives of undocumented immigrants brought to the United States from countries like Mexico or children born in the United States to parents who are undocumented. Asking that those immigrant perspectives be fully captured by, say, individuals who immigrated legally from Europe as adults is likely asking for an imaginative and empathetic leap that will be too much for even the best-intentioned deliberator.

An effective deliberative system should ensure that all relevant perspective holders are heard, and our specific focus is on how the least powerful perspective bearers can be included in civic forums. As Mansbridge (1999) has argued in relation to legislatures, a critical mass of more disadvantaged perspectives may be helpful for several distinct reasons. First, when disempowered perspective holders are present, their voices are more likely to be heard, and the stock of arguments, experiences, reasons, and evidence from disempowered perspectives is likely to be larger. Second, and relatedly, a critical mass may bolster the courage of the disempowered to offer minority viewpoints, and hearing those viewpoints from more than one deliberator may push others – both members of the disempowered group and those who are comparatively more empowered – to take those ideas seriously. Third, in many forums the giving and receiving of reasons occurs not only in large plenary sessions, but also (and crucially) in small break-out sessions and discussion groups, both formal and informal. A critical mass thus increases the likelihood that disempowered perspectives are heard throughout the forum. Fourth, when a greater diversity of disempowered viewpoints is present, no one deliberator is forced to be a token who represents the whole of her social group, a fact that works against an oversimplified, stereotyped, or essentialized view of who the disadvantaged are and what they want.

This is an excerpt of the article, which can be downloaded in full from the Journal of Public Deliberation here.

About the Journal of Public Deliberation

Spearheaded by the Deliberative Democracy Consortium in collaboration with the International Association of Public Participation, the principal objective of Journal of Public Deliberation (JPD) is to synthesize the research, opinion, projects, experiments and experiences of academics and practitioners in the emerging multi-disciplinary field and political movement called by some “deliberative democracy.” By doing this, we hope to help improve future research endeavors in this field and aid in the transformation of modern representative democracy into a more citizen friendly form.

Spearheaded by the Deliberative Democracy Consortium in collaboration with the International Association of Public Participation, the principal objective of Journal of Public Deliberation (JPD) is to synthesize the research, opinion, projects, experiments and experiences of academics and practitioners in the emerging multi-disciplinary field and political movement called by some “deliberative democracy.” By doing this, we hope to help improve future research endeavors in this field and aid in the transformation of modern representative democracy into a more citizen friendly form.

Follow the Deliberative Democracy Consortium on Twitter: @delibdem

Follow the International Association of Public Participation [US] on Twitter: @IAP2USA

Resource Link: www.publicdeliberation.net/jpd/vol12/iss2/art3/

The Anachronist

In the year 1596, Anna is about to be burned at the stake. As the constable prepares to light the fire below her, she can do nothing but seek a solution in her own memory and imagination.

The Anachronist is a game in which you make choices that determine the outcome. By increasing Anna’s knowledge, you can create opportunities for her to act. By decreasing the entropy or disorder of the whole situation, you can raise the odds that the ending will be a happy one for all of the characters. If you try to conclude the story while knowledge is too low or entropy is too high, Anna will burn.

At the same time, The Anachronist is literary fiction. With as many words as a novel, it’s indebted to authors like Joyce, Borges, Calvino, and Pamuk. It uses modernist and post-modernist literary techniques–as well as an interactive format–to explore questions of perspective, historical change, and truth.

Emily Short writes:

The Anachronist is a Twine piece by Peter Levine. It’s long, and paced like a novel rather than like a short story or a poem; it very much belongs to the category of readerly IF [Interactive Fiction]. …

As for what it’s about, that is a little more difficult to describe. The protagonist is being burned at the stake in 1598 (perhaps), but in the moment that she stands in the flame, her mind wanders. She imagines her surroundings in Oxford, or possibly a painting of her surroundings; she thinks about alchemy, the art of memory, the intellectual commitments of a former teacher.

Your task is an abstract one, to do things that globally increase knowledge or decrease entropy. Part of the gameplay involves recognizing and selecting anachronistic references; those links aren’t highlighted for you, but if you succeed in finding something, that counts against entropy.

The knowledge aspect is a little trickier. Most of the choices at least in the early stages of the story are choices either to look more closely at some aspect of the world or else to move onward. My impression was that looking more closely would often increase knowledge, but I’m not certain how consistently that was applied. Some choices overtly claim to have changed your knowledge/entropy status, but I’m not sure that there aren’t other, covert alterations.

I have not yet had the time to read the whole thing. One of the themes so far is a meditation on cultural contact, on how people portray and understand those from other cultures. But that is definitely not the only thing going on, and I’d need to finish the piece in order to say much more.

It’s been online for about three weeks. Some other early readers’ responses are here. Or click to enter the world of The Anachronist.

Participatory Budgeting in Yaounde, Cameroon

Leading Organizational and Community Change

We are happy to share the announcement below about a series of D&D skills trainings being offered at Humboldt State University this year. NCDD Supporting Member Mary Gelinas shared the announcement below via our great Submit-to-Blog Form. Do you have news you want to share with the NCDD network? Just click here to submit your news post for the NCDD Blog!

If you are an elected official, community leader, manager, planner, consultant or facilitator who wants to be even more effective than you already are, these workshops are for you.

The Leading Organizational & Community Change program is a transformative professional development program focused on creating collaboration at work and in your communities. Offered through the College of eLearning and Extended Education at Humboldt State University in Northern California, this program offers courses designed to help organizational managers, community leaders, public officials, city managers, planners, facilitators, and consultants to be more effective in getting things done and creating sustainable change at work, in communities, and in municipalities.

Grounded in the behavioral sciences and brain science, along with effective and innovative process skills and approaches, the curriculum is designed to build your knowledge and develop your skills so you can work more constructively and productively with colleagues, constituents, neighbors, and clients to solve problems, resolve conflicts, build lasting agreements, develop public policy, and plan for the future.

The courses still available in 2017 include:

Consulting Skills: Bringing Our Authentic Selves Forward

Feb. 15-17, 2017

Increase your ability to have a strong and positive impact on your client’s results as a staff person or external consultant or facilitator by applying the eight keys to effective consulting and using the phases of the consulting process. Learn how to establish and maintain effective partnerships with clients and have your expertise and experience more fully utilized.

Graphic Recording

March 16, 2017

Increase your ability to serve meeting participants by writing and drawing their conversation live and large to help them do their work. Graphic Recording is a powerful tool to help people feel heard, develop shared understandings and be able to see their work in real-time.

Effective Meetings: The Key to Getting Things Done

May 11-12, 2017

Effective meetings are the building blocks of creating sustainable change. Learn key elements to build collaboration in meetings in order to get stuff done. Acquire tools to plan and conduct meetings, get and stay focused, and handle difficult behaviors.

Advanced Meeting Leadership for High-Stakes Meetings

August 16-18, 2017

Learn and practice strategies and techniques to design and facilitate high-stakes meetings with complex power and group dynamics. Become more adept at engaging diverse stakeholders in constructive and productive interactions. Practice using your internal state of being, body language, pace and tone to help meetings state on track and move forward.

Designing Multi-Stakeholder Collaborative Change Processes

Oct. 25-27, 2017

Develop the ability to design collaborative and inclusive multi-stakeholder processes to solve complex problems, resolve conflicts, develop a vision, craft a policy, or create change. Learn how various change models can help you plan processes and engage multiple stakeholders in various ways. Understand the key differences between designing change processes for organizations and communities.

For more information, visit www2.humboldt.edu/locc.

Civic Games Contest 2017 – Call for Submissions

The Civic Games Committee (Daniel Levine, Joshua Miller, and Sarah Shugars), with the support of the Entertainment Technology Center at Carnegie Mellon University, are proud to announce the 2017 Civic Games contest, a design competition for analog games that seek to promote the understanding and/or practice of good citizenship!

The contest starts from two fundamental ideas:

- Games can not only provide welcome distraction in dark times, but also help us solve our problems;

- The heart of democracy is not just its institutions, but the convictions, skills, and commitment of its citizens.

For updates, follow our Facebook Page!

What is Civics?

Civics aims to answer questions like: “How can we make democracy work like it should?” or “How can we enhance citizens’ abilities to act as equal co-creators of our shared world?” You are a citizen of a group (regardless of your legal status) if you seriously ask: “What should we do?” (more) Civic activities include deliberation, community organizing, social entrepreneurship, protest, and–in a pinch!–electoral politics.

What is a Civic Game?

A civic game is any game that, in some way, aims to promote or enhance people’s ability to engage with the social and political world around them. Civics can be about working with and within formal structures of government, but it can also be about reforming or opposing injustice, or about being a member of a community in other ways. We welcome games that address any aspect of civics, including:

- Personal: having moral integrity, taking responsibility for one’s actions, reflecting on one’s personal morality

- Communal: openness to dialogue, communal service (e.g., charitable work, helping neighbors), involvement in community organizations (e.g., religious institutions, social clubs)

- Political: engagement with or challenge to formal political structures (e.g., advocacy, protest, running for office, voting, revolution)

There are many ways that a game could address one or more of these themes. For this contest, we’re interested in seeing examples across three categories of games, that we’re calling awareness-raising, skill-building, and inherently political. We plan to pick a winner in each category.

Awareness-Raising

Perhaps the most common type of civic-minded game found among existing games is what we might call awareness-raising games. These are games that educate their players about some important aspect of civic life – they may be historical games that ask player to imagine themselves into a moment political importance, or they may call attention to a contemporary political problem.

There are a lot of very good games out there that fall primarily into the “awareness-raising” category. For example, Moyra Turkington’s Against the Grain asks players to take on the roles of managers and workers in a Baltimore factory producing materials for World War II, on the eve of a wildcat strike protesting the appointment of the factory’s first Black inspector. Playing the game can help players understand the dynamics of race and labor relations in the mid-20th Century US. It may also have aspects of a “skill-building” game, since it encourages players to build empathy for people unlike themselves, or who may seem unlikeable or to hold odious political views.

Skill-Building

A different approach, which we’ll call skill-building, aims to better prepare the players to take political action outside of the game – a game that, for example, simulated canvassing for a political candidate and thereby made players more comfortable actually doing it, would fall into this category. Despite the term “skill,” we understand this category to include games that build dispositions to take political action as well – say, games that build empathy for people experiencing some problem, and make the players more likely to act to alleviate it.

Nomic was designed by Peter Suber to illustrate a conceptual puzzle about legal systems that direct and constrain their own amendment: “Nomic is a game in which changing the rules is a move. In that respect it differs from almost every other game. The primary activity of Nomic is proposing changes in the rules, debating the wisdom of changing them in that way, voting on the changes, deciding what can and cannot be done afterwards, and doing it. Even this core of the game, of course, can be changed.” Nomic has many elements that teach and build the skills of designing and debating social rules. It may also have an awareness-raising component, of course: serious games of Nomic usually begin with democratic voting procedures but often end undemocratic.

The National Coalition for Deliberation and Dialogue maintains a list of participatory practices for which practitioners might need to build their skills based on an earlier “Citizen Science Toolbox” of Process Arts. Feel free to use it for inspiration.

Inherently Political

Finally, some games might be inherently political themselves, where playing the game is an act of civic engagement. A simple example – we’re sure you can come up with a better idea! – would be “gamifying” voting, recycling, or participation in local governance, giving points for those activities that could then be used for some in-game purpose.

Games have been incorporated into real-world political processes such as such as participatory budgeting. Most famously implemented in the Brazilian city of Porto Alegre, this process in that case allowed ordinary citizens to identify, discuss, and ultimately set budget priorities for $200 million in construction and service projects in the city. Many American cities are also experimenting with participatory budgeting, including New York City, Boston, and San Francisco. In 2011, community leaders in San Jose, CA were invited to an event to play a budget-negotiation game, the results of which were then used by the city government in making actual budget decisions – meaning that, at least in this case, playing the game was an inherently political act with real-world impact.

Submission Guidelines and Rules

- Your game must be an analog game – that is, not a video game. Analog games include role-playing games (both those played at a table and live-action games), card games, and board games. Your game may have electronic components (e.g., an mp3 played as part of the game play, an associated phone app), but the core of its play should be non-electronic. There may be weird corner cases – we’ll try to be generous.

- We will try to be broad-minded about what constitutes a game – however, note below that part of our judging rubric includes playability and fun, so experimental projects may be formally intriguing but will be at a disadvantage in this context. We are looking for games that people will want to play, even independent of their civic content.

- All components of your game must be able to be sent to the judges in electronic format. If there are pieces that need to be printed out to actually play (e.g., print-and-play board game components), that’s fine.

- Your game’s text and any required printable components should not exceed either 5,000 words or ten printed pages (that is, it shouldn’t be more than either – if you have eight pages of printable components, please don’t also send ten pages with 5,000 words of rules text). We very much welcome shorter games (and brevity is often a plus for accessibility, see below).

- Currently, we only have English-language judges; please provide all text in English. We encourage you to provide it in other languages as well, if you can, though judges will refer to the English text.

- Games submitted for this contest cannot have been previously published, or made publicly available in completed form for free, prior to submission. You may draw on previously published materials; compliance with all relevant intellectual property rules is the responsibility of the submitter. Basically: don’t just send us a game you already have lying around, don’t steal stuff.

- You may submit materials that are intended for use with another game, subject to a couple caveats:

- We are looking for complete experiences that can be used in a relatively self-contained fashion. So, we would accept something like a module intended to be run with the Swords and Wizardry rules. But a set of playbooks for Apocalypse World (The Politico, The Fact-Checker, etc.) is not the sort of thing we’re looking for.

- Any materials required to use your game may impact its scoring on accessibility (see below). Basically, if you need $200 worth of rulebooks and supplements to play your game, that will count against you.

- Teams may submit games. Your name may only be on a maximum of one solo submission and one team submission.

- Submissions are due by midnight on 15 April 2017. Please send all submissions to civicgames17@gmail.com. Don’t forget to include your name(s) as you’d like them to appear in any mention of your game.

Other Rules

- You retain all rights to your game. However, by submitting your game to the contest, you are agreeing to allow us to:

- Make any copies of the game necessary for the judging process, in physical or electronic format.

- Distribute your game in print or electronic format, for free, to participants in the 2017 Frontiers of Democracy conference.

- Make your game available for free via our website (in electronic format).

- Instruct people who receive your game from us at the conference or via the website that they are permitted to download it and make copies (physical or electronic) for personal use, educational use, or use in political activism.

- Include language in any copy of your game we distribute that indicates that it was a submission to the 2017 Civic Games Contest, that the contest was sponsored by the Entertainment Technology Center at Carnegie Mellon University, and that the game can be copied for personal, educational, or activist use.

- If you decide that you would like to withdraw these permissions, you must do so before judging begins on 15 April 2017, by notifying us in writing at civicgames17@gmail.com. If you withdraw these permissions, your game will not be considered for any award.

- Submitting your game to the contest means you are representing yourself as having the right to give us these permissions.

- We reserve the right to decline to make any game available on the website, at our discretion.

- If you are selected as an overall winner or a winner in a special category, you may be offered the opportunity to have your game published in The Good Society (see below). If (and only if) you choose to do so, you will need to transfer copyright to the journal. No winner will be required to publish in the journal if they prefer not to.

How will you pick a winner?

We’re looking for games that work as games as well as as educational or activist experiences – our ideal game is one that people who had no idea it had a civic purpose would still want to play. More specifically, our judges will be assessing games for:

- Fun: Does this game look like it’ll provide an experience of play that people will seek out and appreciate? We recognize that “fun” may not be quite the same as happy-making or enjoyable – a deeply engaging tragic story can be “fun” in the relevant sense.

- Civic Impact: How likely is this game to achieve some civic purpose through its play? Will people who play the game leave more aware of some civic issue or history? Will they acquire new skills? Will they change the world for the better through play of the game?

- Accessibility: Is this game open to a wide range of players? Does it have rules that are easy to teach and learn? Is its social footprint one that people can integrate into their lives? Does it take steps to ensure that physical/mental impairments and limited resources are mitigated as barriers to play? This is an issue that still needs a lot of work, and we’re hoping some innovations may come out of this contest! Accessible Games has some resources and information. You can find some solid ideas for accessibility in video games here, which has some advice relevant for analog games. There’s an interesting discussion of accessibility in board games in these two blog posts as well.

- Inclusivity: Does this game speak either to a broad range of experiences, or to experiences less often addressed in games and/or mainstream discussions of civics? Does the game address issues of race, class, gender, sexual orientation, disability, or related divides in interesting and worthwhile ways? If you’ve got a kick-butt game about the operation of a bicameral legislature, that’s great – but we want you to at least consider taking note of the fact that sometimes bicameral legislatures have their operations affected by sit-ins, or that Montesquieu proposed the notion of a bicameral legislature to ensure that nobles would have a voice to check that of the people.

We will select one overall winner for each type of game – awareness-raising, skill-building, and inherently political. We may also decide to award special recognition to games that make a particular contribution in one of our areas of interest or genre-bend in ways we did not predict.

The games will be judged by a panel of six fabulous game designers, game theorists, and scholars of civics:

- Laura Simpson, UX designer and author of “Driving to the Reunion” (part of the #feminism game anthology) and The Companion’s Tale.

- Jessica Hammer, Assistant Professor at Carnegie Mellon University (Human Computer Interaction Institute/Entertainment Technology Center)

- Trygve Throntveit, Dean’s Fellow for Civic Studies at the University of Minnesota College of Education and Human Development, Editor of The Good Society, and author of William James and the Quest for an Ethical Republic.

- Alison Staudinger, Assistant Professor of Democracy and Justice Studies, University of Wisconsin-Green Bay, co-editor of the forthcoming Gender in Teaching and Learning Political Science and author of a forthcoming book based on her dissertation, Work Under Democracy: Labor, Gender, and Arendtian Citizenship.

- James Mendez Hodes, staff writer on the new edition of 7th Sea, translator of Tha Illiad of MC Homer, and author of the upcoming game AfroFuture.

- Adam Dray, editor of Misspent Youth and carry: a game about war.

What Do I Win?

Mostly, bragging rights and the knowledge that you’ve created something that might make the world a better place. We will announce the winners via the website on 1 June 2017.

In addition, the three overall winners will have their games presented at the Frontiers of Democracy conference in late June 2017. Frontiers is the birthplace of civic-studies and the field’s premier conference. It will be a chance for your game to be known by educators and scholars from around the world. We will work with you to develop a 30-minute demo of your game (if it is not already played in a similarly short time-frame). Thanks to a generous sponsorship by the Entertainment Technology Center at Carnegie Mellon University, any winners who are able to attend the conference will have their entry fees covered. We will work with winners who cannot attend the conference to set up a video question-and-answer period after the presentation of their game.

In addition, the three winning games, along with any other special category winners that space permits, will be considered for publication in a special section of the journal The Good Society.

Who is the Civic Games Committee?

Really, we’re just a few friends, who share an interest in both tabletop games and deepening democracy, who had an idea and decided to see if it had legs. We hope it does!

- Daniel H. Levine is the School Mediation Coordinator for Baltimore City Community Mediation, and a co-founder of the Jessup Correctional Institution (JCI) Prison Scholars Program. In a previous life, he was an Assistant Professor of Public Policy at the University of Maryland and a Program Officer in the Education and Training (International) program at the US Institute of Peace. In a future life he is working on a game about the Abortion Counseling Service of Women’s Liberation (aka “Jane”).

- Joshua A. Miller is the Assistant Director of the Second Chance program at the University of Baltimore, which offers a degree in Community Studies and Civic Engagement to incarcerated men; he is also a founder of the JCI Prison Scholars Program. His heart will be especially warmed by any civic-minded Ars Magica hacks we receive.

- Sarah Shugars is a doctoral student in Network Science at Northeastern University. She received her BA in Physics from Clark University, where she graduated Cum Laude in 2004. She received her MA in Integrated Marketing Communications from Emerson College in 2009, and participated in Tisch College’s Summer Institute of Civic Studies in 2013. An active member of the Somerville, MA community, Sarah serves as vice president of The Welcome Project board and on the board of the OPENAIR Circus.

I Have Questions!

Please contact us at civicgames17@gmail.com and we’ll do our best.

Special thanks to James Mendez Hodes, Jessica Hammer, Laura Simpson, Jason Morningstar, Graham W, and Nick Wedig for their input on this document. Any remaining errors or infelicities are the sole responsibility of the Committee.

Civic Games Contest 2017 – Call for Submissions

The Civic Games Committee (Daniel Levine, Joshua Miller, and Sarah Shugars), with the support of the Entertainment Technology Center at Carnegie Mellon University, are proud to announce the 2017 Civic Games contest, a design competition for analog games that seek to promote the understanding and/or practice of good citizenship!

The contest starts from two fundamental ideas:

- Games can not only provide welcome distraction in dark times, but also help us solve our problems;

- The heart of democracy is not just its institutions, but the convictions, skills, and commitment of its citizens.

For updates, follow our Facebook Page!

What is Civics?

Civics aims to answer questions like: “How can we make democracy work like it should?” or “How can we enhance citizens’ abilities to act as equal co-creators of our shared world?” You are a citizen of a group (regardless of your legal status) if you seriously ask: “What should we do?” (more) Civic activities include deliberation, community organizing, social entrepreneurship, protest, and–in a pinch!–electoral politics.

What is a Civic Game?

A civic game is any game that, in some way, aims to promote or enhance people’s ability to engage with the social and political world around them. Civics can be about working with and within formal structures of government, but it can also be about reforming or opposing injustice, or about being a member of a community in other ways. We welcome games that address any aspect of civics, including:

- Personal: having moral integrity, taking responsibility for one’s actions, reflecting on one’s personal morality

- Communal: openness to dialogue, communal service (e.g., charitable work, helping neighbors), involvement in community organizations (e.g., religious institutions, social clubs)

- Political: engagement with or challenge to formal political structures (e.g., advocacy, protest, running for office, voting, revolution)

There are many ways that a game could address one or more of these themes. For this contest, we’re interested in seeing examples across three categories of games, that we’re calling awareness-raising, skill-building, and inherently political. We plan to pick a winner in each category.

Awareness-Raising

Perhaps the most common type of civic-minded game found among existing games is what we might call awareness-raising games. These are games that educate their players about some important aspect of civic life – they may be historical games that ask player to imagine themselves into a moment political importance, or they may call attention to a contemporary political problem.

There are a lot of very good games out there that fall primarily into the “awareness-raising” category. For example, Moyra Turkington’s Against the Grain asks players to take on the roles of managers and workers in a Baltimore factory producing materials for World War II, on the eve of a wildcat strike protesting the appointment of the factory’s first Black inspector. Playing the game can help players understand the dynamics of race and labor relations in the mid-20th Century US. It may also have aspects of a “skill-building” game, since it encourages players to build empathy for people unlike themselves, or who may seem unlikeable or to hold odious political views.

Skill-Building

A different approach, which we’ll call skill-building, aims to better prepare the players to take political action outside of the game – a game that, for example, simulated canvassing for a political candidate and thereby made players more comfortable actually doing it, would fall into this category. Despite the term “skill,” we understand this category to include games that build dispositions to take political action as well – say, games that build empathy for people experiencing some problem, and make the players more likely to act to alleviate it.

Nomic was designed by Peter Suber to illustrate a conceptual puzzle about legal systems that direct and constrain their own amendment: “Nomic is a game in which changing the rules is a move. In that respect it differs from almost every other game. The primary activity of Nomic is proposing changes in the rules, debating the wisdom of changing them in that way, voting on the changes, deciding what can and cannot be done afterwards, and doing it. Even this core of the game, of course, can be changed.” Nomic has many elements that teach and build the skills of designing and debating social rules. It may also have an awareness-raising component, of course: serious games of Nomic usually begin with democratic voting procedures but often end undemocratic.

The National Coalition for Deliberation and Dialogue maintains a list of participatory practices for which practitioners might need to build their skills based on an earlier “Citizen Science Toolbox” of Process Arts. Feel free to use it for inspiration.

Inherently Political

Finally, some games might be inherently political themselves, where playing the game is an act of civic engagement. A simple example – we’re sure you can come up with a better idea! – would be “gamifying” voting, recycling, or participation in local governance, giving points for those activities that could then be used for some in-game purpose.

Games have been incorporated into real-world political processes such as such as participatory budgeting. Most famously implemented in the Brazilian city of Porto Alegre, this process in that case allowed ordinary citizens to identify, discuss, and ultimately set budget priorities for $200 million in construction and service projects in the city. Many American cities are also experimenting with participatory budgeting, including New York City, Boston, and San Francisco. In 2011, community leaders in San Jose, CA were invited to an event to play a budget-negotiation game, the results of which were then used by the city government in making actual budget decisions – meaning that, at least in this case, playing the game was an inherently political act with real-world impact.

Submission Guidelines and Rules

- Your game must be an analog game – that is, not a video game. Analog games include role-playing games (both those played at a table and live-action games), card games, and board games. Your game may have electronic components (e.g., an mp3 played as part of the game play, an associated phone app), but the core of its play should be non-electronic. There may be weird corner cases – we’ll try to be generous.

- We will try to be broad-minded about what constitutes a game – however, note below that part of our judging rubric includes playability and fun, so experimental projects may be formally intriguing but will be at a disadvantage in this context. We are looking for games that people will want to play, even independent of their civic content.

- All components of your game must be able to be sent to the judges in electronic format. If there are pieces that need to be printed out to actually play (e.g., print-and-play board game components), that’s fine.

- Your game’s text and any required printable components should not exceed either 5,000 words or ten printed pages (that is, it shouldn’t be more than either – if you have eight pages of printable components, please don’t also send ten pages with 5,000 words of rules text). We very much welcome shorter games (and brevity is often a plus for accessibility, see below).

- Currently, we only have English-language judges; please provide all text in English. We encourage you to provide it in other languages as well, if you can, though judges will refer to the English text.

- Games submitted for this contest cannot have been previously published, or made publicly available in completed form for free, prior to submission. You may draw on previously published materials; compliance with all relevant intellectual property rules is the responsibility of the submitter. Basically: don’t just send us a game you already have lying around, don’t steal stuff.

- You may submit materials that are intended for use with another game, subject to a couple caveats:

- We are looking for complete experiences that can be used in a relatively self-contained fashion. So, we would accept something like a module intended to be run with the Swords and Wizardry rules. But a set of playbooks for Apocalypse World (The Politico, The Fact-Checker, etc.) is not the sort of thing we’re looking for.

- Any materials required to use your game may impact its scoring on accessibility (see below). Basically, if you need $200 worth of rulebooks and supplements to play your game, that will count against you.

- Teams may submit games. Your name may only be on a maximum of one solo submission and one team submission.

- Submissions are due by midnight on 15 April 2017. Please send all submissions to civicgames17@gmail.com. Don’t forget to include your name(s) as you’d like them to appear in any mention of your game.

Other Rules

- You retain all rights to your game. However, by submitting your game to the contest, you are agreeing to allow us to:

- Make any copies of the game necessary for the judging process, in physical or electronic format.

- Distribute your game in print or electronic format, for free, to participants in the 2017 Frontiers of Democracy conference.

- Make your game available for free via our website (in electronic format).

- Instruct people who receive your game from us at the conference or via the website that they are permitted to download it and make copies (physical or electronic) for personal use, educational use, or use in political activism.

- Include language in any copy of your game we distribute that indicates that it was a submission to the 2017 Civic Games Contest, that the contest was sponsored by the Entertainment Technology Center at Carnegie Mellon University, and that the game can be copied for personal, educational, or activist use.

- If you decide that you would like to withdraw these permissions, you must do so before judging begins on 15 April 2017, by notifying us in writing at civicgames17@gmail.com. If you withdraw these permissions, your game will not be considered for any award.

- Submitting your game to the contest means you are representing yourself as having the right to give us these permissions.

- We reserve the right to decline to make any game available on the website, at our discretion.

- If you are selected as an overall winner or a winner in a special category, you may be offered the opportunity to have your game published in The Good Society (see below). If (and only if) you choose to do so, you will need to transfer copyright to the journal. No winner will be required to publish in the journal if they prefer not to.

How will you pick a winner?

We’re looking for games that work as games as well as as educational or activist experiences – our ideal game is one that people who had no idea it had a civic purpose would still want to play. More specifically, our judges will be assessing games for:

- Fun: Does this game look like it’ll provide an experience of play that people will seek out and appreciate? We recognize that “fun” may not be quite the same as happy-making or enjoyable – a deeply engaging tragic story can be “fun” in the relevant sense.

- Civic Impact: How likely is this game to achieve some civic purpose through its play? Will people who play the game leave more aware of some civic issue or history? Will they acquire new skills? Will they change the world for the better through play of the game?

- Accessibility: Is this game open to a wide range of players? Does it have rules that are easy to teach and learn? Is its social footprint one that people can integrate into their lives? Does it take steps to ensure that physical/mental impairments and limited resources are mitigated as barriers to play? This is an issue that still needs a lot of work, and we’re hoping some innovations may come out of this contest! Accessible Games has some resources and information. You can find some solid ideas for accessibility in video games here, which has some advice relevant for analog games. There’s an interesting discussion of accessibility in board games in these two blog posts as well.

- Inclusivity: Does this game speak either to a broad range of experiences, or to experiences less often addressed in games and/or mainstream discussions of civics? Does the game address issues of race, class, gender, sexual orientation, disability, or related divides in interesting and worthwhile ways? If you’ve got a kick-butt game about the operation of a bicameral legislature, that’s great – but we want you to at least consider taking note of the fact that sometimes bicameral legislatures have their operations affected by sit-ins, or that Montesquieu proposed the notion of a bicameral legislature to ensure that nobles would have a voice to check that of the people.

We will select one overall winner for each type of game – awareness-raising, skill-building, and inherently political. We may also decide to award special recognition to games that make a particular contribution in one of our areas of interest or genre-bend in ways we did not predict.

The games will be judged by a panel of six fabulous game designers, game theorists, and scholars of civics:

- Laura Simpson, UX designer and author of “Driving to the Reunion” (part of the #feminism game anthology) and The Companion’s Tale.

- Jessica Hammer, Assistant Professor at Carnegie Mellon University (Human Computer Interaction Institute/Entertainment Technology Center)

- Trygve Throntveit, Dean’s Fellow for Civic Studies at the University of Minnesota College of Education and Human Development, Editor of The Good Society, and author of William James and the Quest for an Ethical Republic.

- Alison Staudinger, Assistant Professor of Democracy and Justice Studies, University of Wisconsin-Green Bay, co-editor of the forthcoming Gender in Teaching and Learning Political Science and author of a forthcoming book based on her dissertation, Work Under Democracy: Labor, Gender, and Arendtian Citizenship.

- James Mendez Hodes, staff writer on the new edition of 7th Sea, translator of Tha Illiad of MC Homer, and author of the upcoming game AfroFuture.

- Adam Dray, editor of Misspent Youth and carry: a game about war.

What Do I Win?

Mostly, bragging rights and the knowledge that you’ve created something that might make the world a better place. We will announce the winners via the website on 1 June 2017.

In addition, the three overall winners will have their games presented at the Frontiers of Democracy conference in late June 2017. Frontiers is the birthplace of civic-studies and the field’s premier conference. It will be a chance for your game to be known by educators and scholars from around the world. We will work with you to develop a 30-minute demo of your game (if it is not already played in a similarly short time-frame). Thanks to a generous sponsorship by the Entertainment Technology Center at Carnegie Mellon University, any winners who are able to attend the conference will have their entry fees covered. We will work with winners who cannot attend the conference to set up a video question-and-answer period after the presentation of their game.

In addition, the three winning games, along with any other special category winners that space permits, will be considered for publication in a special section of the journal The Good Society.

Who is the Civic Games Committee?

Really, we’re just a few friends, who share an interest in both tabletop games and deepening democracy, who had an idea and decided to see if it had legs. We hope it does!

- Daniel H. Levine is the School Mediation Coordinator for Baltimore City Community Mediation, and a co-founder of the Jessup Correctional Institution (JCI) Prison Scholars Program. In a previous life, he was an Assistant Professor of Public Policy at the University of Maryland and a Program Officer in the Education and Training (International) program at the US Institute of Peace. In a future life he is working on a game about the Abortion Counseling Service of Women’s Liberation (aka “Jane”).

- Joshua A. Miller is the Assistant Director of the Second Chance program at the University of Baltimore, which offers a degree in Community Studies and Civic Engagement to incarcerated men; he is also a founder of the JCI Prison Scholars Program. His heart will be especially warmed by any civic-minded Ars Magica hacks we receive.

- Sarah Shugars is a doctoral student in Network Science at Northeastern University. She received her BA in Physics from Clark University, where she graduated Cum Laude in 2004. She received her MA in Integrated Marketing Communications from Emerson College in 2009, and participated in Tisch College’s Summer Institute of Civic Studies in 2013. An active member of the Somerville, MA community, Sarah serves as vice president of The Welcome Project board and on the board of the OPENAIR Circus.

I Have Questions!

Please contact us at civicgames17@gmail.com and we’ll do our best.

Special thanks to James Mendez Hodes, Jessica Hammer, Laura Simpson, Jason Morningstar, Graham W, and Nick Wedig for their input on this document. Any remaining errors or infelicities are the sole responsibility of the Committee.

Snow Days

Snow days can cause chaos insofar as everything that was scheduled for a snow day needs to be rescheduled for a subsequent day; perhaps even the immediately following day – thus cramming two days of work into one.

Which is surprising, perhaps, because the snow day itself had no shortage of work either.

But somehow time just got all messed up; after a snow day things just don’t quite occur in the right order any more.

But I appreciate snow days as a humbling experience – they come as a reminder that sometimes even the most pressing meetings can still survive being postponed for a day.