Crime, poverty, tyranny, racial injustice, and environmental degradation may be among the chief issues at a given time. But beneath such specific challenges are general forms of problems. To reprise a diagram from a previous post, we face problems of discourse (when we think or want the wrong things) and problems of collective action (when we can’t get what we want).

Academics certainly study these problems. Google Scholar finds more than 77,000 books or articles on free-riding, which is one variety of a collective action problem. It finds more than 9,000 citations of implicit bias, which I would categorize as a discourse problem. There is no shortage of material to read, and much of it is useful.

Academics certainly study these problems. Google Scholar finds more than 77,000 books or articles on free-riding, which is one variety of a collective action problem. It finds more than 9,000 citations of implicit bias, which I would categorize as a discourse problem. There is no shortage of material to read, and much of it is useful.

But the study of human problems and their solutions suffers from three general  limitations that we should address:

limitations that we should address:

- Too little attention is paid to what we (you and I and the people we can influence) are able to do. For instance, pumping carbon into the air is a classic harmful externality. It’s serious enough that it threatens our survival. Economics offers a solution: tax the carbon. The tax might not even have to be very high, and other tax cuts could offset it. That sounds like the answer, but it isn’t something that we (you and I and our friends and colleagues) can implement. We lack the power to set taxes. Even if we formed the body of the US Congress, we couldn’t tax carbon in China. So the proposal to tax carbon is not the solution; it just poses new problems that we must define, analyze, and address in ways that guide our actions. (By the way, several of the most common proposed solutions are inadequate. For instance, we cannot vote for candidates who would tax carbon unless such candidates actually run, have a chance of winning, and hold a whole platform of ideas that we endorse. Also, we cannot just voluntarily cut our own carbon emissions and hope that others do as well. So what should we do?)

- The moral question (what is right and good?) is too often sidelined. Although the diagrams shown above list “problems,” these phenomena are not necessarily bad. For instance, when we promote competition among firms by preventing them from coordinating their prices, we are putting them in a Prisoner’s Dilemma. That is desirable because it’s better for profits and prices to be low. But when nonprofits compete instead of collaborating on the common good, that is damaging. So I say–but clearly, I owe an argument for those judgments. An underlying theory of justice must determine which Prisoner’s Dilemmas are good and bad. Some of the prevalent methods for deciding what constitutes a problem–or a solution–are morally indefensible. For example, neither false consciousness as a methodological tool on the left nor Pareto optimality on the right will reliably distinguish right from wrong. So what is right for us to do?

- Theory is insufficiently exploited as a resource. Sometimes people teach and investigate social problems in highly experiential ways, by rolling up their sleeves and tackling issues like homelessness or habitat loss in specific programs, classes, or other projects. Much can be learned from experience, which is why I am a lifelong advocate of civic engagement in k-12 schools and colleges. And yet, if you invite a group of people to choose, define, and address a problem from scratch, you are asking them to reinvent the whole history of thought. You may inspire them by telling them, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world.” But when they fail to improve the world, as they almost always will, their sense of self-confidence will fall–as seen consistently across a wide range of programs. It is hard enough to make noticeable progress on entrenched challenges without taking full advantage of the accumulated and organized analysis of other people. So what is smart for us to do?

The nascent Civic Studies movement proposes to ask “What should we do?” and then take very seriously the various generic forms of human problems–along with explicit moral argumentation. Three benefits should follow. We should unify our understanding of the various genera of problems–which are now distributed across the social sciences and humanities–by viewing them from a single perspective, that of a reflective small group of citizens. We should enhance human agency and satisfaction by making ourselves the cause of solutions, not just the objects of other people’s actions. Above all, we should actually improve the world by identifying solutions that we (you and I and our friends) can accomplish.

To give a little more concreteness to the list of problems, I will briefly discuss some of the key ones. This is a radically incomplete list; and the discussion of each one below is highly preliminary. The point is to indicate the agenda of Civic Studies.

- Discourse Problems

- Ideology: This word can be defined in various ways, but I have in mind a systematic distortion of one’s beliefs and preferences due to an overall theory that is wrong. For instance, some people believe that the United States was once a welfare state with a social safety net that has been badly frayed because of neoliberalism. And other people believe that the United States was once a society of free, self-reliant entrepreneurs that is now becoming socialist. They cannot both be right. If either belief or (as I happen to think) both beliefs are wrong, then we have a problem of ideology, because these ideas are prevalent and influential.

- Implicit Bias: In experiments using fictional resumes, “White-sounding names (e.g., Emily, Greg, Sarah, Todd) received 50 percent more callbacks for interviews than resumes with African American-sounding names (e.g., Lakisha, Jamal, Latoya, Tyrone) (Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2004). Putting this in perspective, ‘a White name yields as many more callbacks as an additional eight years of experience on a resume’ (Bertrand & Mullainathan, 2004, p. 992).” That is evidence of a bias that is pervasive and damaging even if it is unconscious and unintended. Implicit bias is not limited to matters of race and seems to be extraordinarily common.

Motivated Reasoning: We are good at selecting and emphasizing facts that support our pre-determined ideas, and equally good at marginalizing or debunking facts that complicate or challenge those ideas. For example, as people obtain more education, their opinion about climate change correlates more with their political ideology. Conservatives become less likely to believe in it, and liberals more so, the more education they have. Why? Because well-educated conservatives are sophisticated enough to recognize that accepting evidence of climate change would challenge their economic views, so they use mental techniques (also exhibited by liberals on other topics) to debunk or marginalize the evidence. Many studies find that deliberate efforts to debunk myths actually reinforce the same myths because people hear the information selectively.

Motivated Reasoning: We are good at selecting and emphasizing facts that support our pre-determined ideas, and equally good at marginalizing or debunking facts that complicate or challenge those ideas. For example, as people obtain more education, their opinion about climate change correlates more with their political ideology. Conservatives become less likely to believe in it, and liberals more so, the more education they have. Why? Because well-educated conservatives are sophisticated enough to recognize that accepting evidence of climate change would challenge their economic views, so they use mental techniques (also exhibited by liberals on other topics) to debunk or marginalize the evidence. Many studies find that deliberate efforts to debunk myths actually reinforce the same myths because people hear the information selectively.- Polarization: Numerous studies have found that groups on one general side of an issue will migrate toward more radical opinions as a result of interacting. Groups that span a wide spectrum of opinion will often polarize into relatively radical opposing subgroups. One of several reasons is that individuals want to be accepted into a group of like-minded peers.

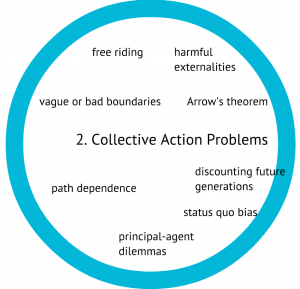

- Collective Action Problems

- Principal-agent problems: An “agent” is someone whom a “principal” employs to take care of her interests. For instance, I employ my dentist to take care of my teeth. But my dentist’s interests may diverge from mine: for instance, if expensive surgery is an option. The same divergence can occur in political contexts. Almost all Americans believe that money has too much influence in politics and should be curtailed. Yet for decades before the Supreme Court got in the way, Congress did very little to restrain private money in politics, even when the Democrats (who were rhetorically opposed to it) controlled both branches of government. Why? Because politicians are agents of citizens, and as agents who have been elected in a system of unrestricted private money, they have different interests from their principals.

- Free riders: It is often tempting to let other people carry the burden for a public good, in which case the good may not be provided even if everyone wants it. Examples range from a failure to clean the dishes in a group house to the failure of nations to limit their carbon emissions.

- Path dependence: We might all be better off if, a century ago, cars had been developed to use electricity instead of gasoline. By the 21st century, electric cars would be fantastically fuel-efficient and convenient. But the petroleum path was chosen, and now to shift to electricity is very expensive and difficult–so much so that it might even be unwise.

- Arrow’s Impossibility Theorem: It has been logically proven that no system for turning votes into decisions can simultaneously meet several obvious criteria. In practical terms, the main implication is that we must choose between voting systems that force a two-sided choice (like referenda or two-party elections) or voting systems that allow many to win small shares of power (as in Israeli elections). The former systems disadvantage anyone who is dissatisfied with the forced choice. The latter can lead to stalemate or unpopular minority rule.

A subset of these problems will typically confront any concrete group of human beings who aim to improve their world. In many circumstances, the various problems will closely interrelate, causing webs or cycles of challenges. For instance, ideology may prevail over good evidence (a discourse problem) because the effort to become truly informed about public issues is not worthwhile for each party (a collective action problem).

Yet–and this is a crucial point–groups of people do solve human problems. They do build institutions and norms that make life better. Every decent and functioning government, association, neighborhood, and network is a triumph of reasonable hope over chastened experience. The master theorists of Civic Studies are people like Elinor Ostrom and Jürgen Habermas (a student, respectively, of collective-action problems and of discourse problems), who seek to understand in order to defend, improve, and spread such cases of human success.

See also Ostrom plus Habermas is nearly all we need; my piece on Civic Studies in Philosophy & Public Policy Quarterly; the book Civic Studies: Approaches to the Emerging Field; and The Good Society symposium on Civic Studies.

The post a different approach to human problems appeared first on Peter Levine.