I am a steadfast supporter of Ukrainian resistance, and I encourage Ukrainian friends to skip this post if it feels like a distraction from their crisis. Still, those of us in noncombatant countries face subtle ethical questions that arise with all such conflicts. How we resolve these issues probably won’t have an appreciable impact on the war in Ukraine–and if we can affect the outcome, I would be biased in favor of choices that benefit the resistance. Instead, these are mainly questions about our own internal processes and principles.

Consider these cases:

- The Metropolitan Opera is one of many cultural institutions that has announced that it will not work with pro-Putin Russian artists. The Met’s ban could affect soprano Anna Netrebko, who had demonstrated active support for the separatists in eastern Ukraine but who has also posted on Instagram that she opposes the war, while adding that “forcing artists, or any public figure, to voice their political opinions in public and to denounce their homeland is not right.” (From Javier C. Hernandez in the New York Times.)

- There are calls to ban former German Chancellor Gerhardt Schroeder (a former leader of an EU and NATO country) from entering the UK. Of note: Schroeder is not only close to Putin and unwilling to criticize the invasion of Ukraine, but he was a director of the state-controlled Russian energy company, Rosneft.

- “The Russian filmmaker Kirill Sokolov has spent the past week distraught at the horror unfolding in Ukraine. Half his family is Ukrainian, he said in a telephone interview, and as a child he spent summers there, staying with his grandparents. … Yet despite his antiwar stance, Mr. Sokolov on Monday learned that the Glasgow Film Festival in Scotland had dropped his latest movie, ‘No Looking Back.’ A spokeswoman for the festival said in an email that Mr. Sokolov’s film … had received Russian state funding. The decision to exclude the movie was not a reflection on the filmmaker himself, she said.” (From Alex Marshall in the Times.)

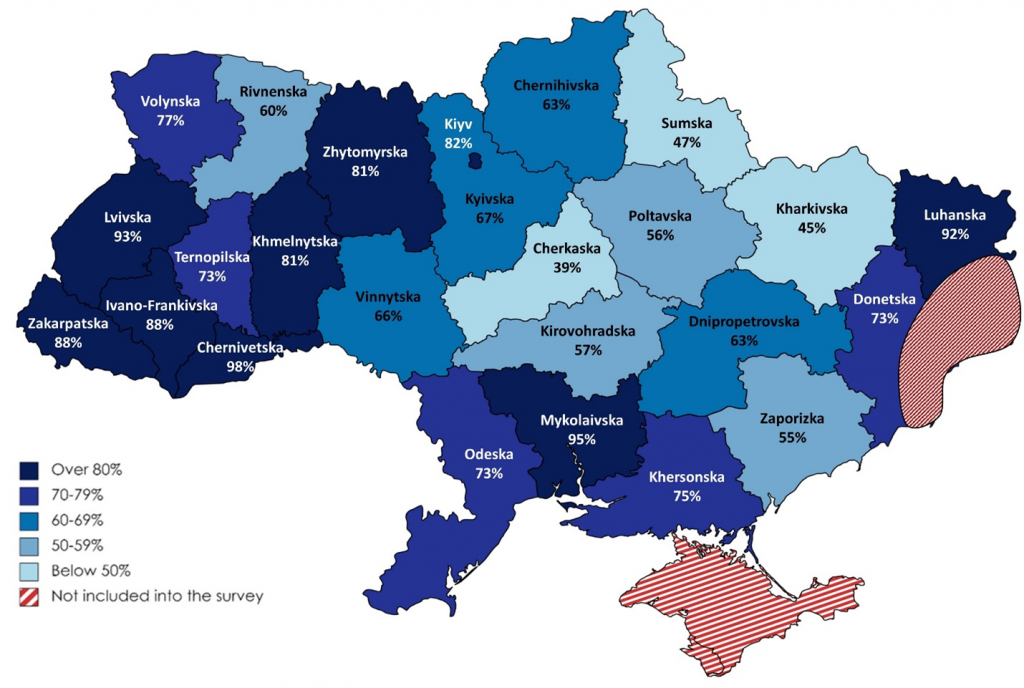

- The Alliance of Science Organizations in Germany is one of the biggest science funders that has announced a complete ban on grants, events, and collaborations with Russia. Meanwhile, 5,000 people, mostly Russian scientists, including 85 members of the Russian Academy of Sciences, have publicly signed a strong anti-war statement. They will be affected by the German boycott.

- Yelena Balanovskaya and her family hold a mortgage on their Moscow apartment that is dominated in US dollars, meaning that they cannot afford their payments and may lose their home. Nothing is said in the article about Ms. Balanovskaya’s political views.

- Afghanistan is suffering a nightmare winter, and the sanctions targeting Russia may be making matters worse.

Although I strongly support the sanctions on Russia, I think the ethical issues are complex. We must navigate principles that are in some tension.

First, working with an individual can be a discretionary choice, and it may be appropriate to consider that person’s values. In general, you shouldn’t have to work with a racist–or a Putin-apologist–if you don’t want to. I serve regularly on search committees and would be hard-pressed to give my support to a pro-Putin job candidate, even if the position had nothing to do with politics, just because I wouldn’t want to work with that person. I think a refusal to engage with specific individuals is an exercise of freedom, just like their choice to express their opinions.

On the other hand, when an institution–even a small, private one–decides to include or exclude individuals based on their opinions, several hard problems arise. Suddenly, we are in the business of assessing people’s thoughts, and that can be invasive as well as unreliable. Tyler Cowan asks, “What about performers who may have favored Putin in the more benign times of 2003 and now are skeptical, but have family members still living in Russia? Do they have to speak out? Another question: Who exactly counts as Russian? Ethnic Russians? Russian citizens? Former citizens? Ethnic Russians born in Ukraine?” I would add: What about leftist critics of US imperialism who have justified Putin’s policies to various degrees over time? Would we ban editors of The Nation? And if we apply this screen to Russia/Ukraine, why not to other conflicts and injustices?

Slippery-slope arguments are sometimes classified as fallacies. Just because bad behavior falls on a continuum, it doesn’t follow that we should do nothing about any of it. But when the question is whether to work with individuals, it is morally imperative to employ clear and consistent standards. Such standards are difficult to define and maintain when everyone holds a unique constellation of opinions, and particularly when people may be afraid to say everything they believe.

Another problem with “de-platforming” or “canceling” individuals is the risk of reinforcing polarization. We can easily end up with homogeneously liberal cultural institutions (and even ordinary businesses), which then lose their ability to influence the illiberal people whom they have excluded. This is true of US universities, which risk alienating enough American conservatives that they undermine their influence over the culture. Likewise, do we want to undermine our own soft power in Russia by excluding Russians?

In a confusing time, it may be best to send the simple message that we are an open, pluralist society that does not fear abhorrent views or despise anyone because of their ethnicity–in fact, we oppose ethno-national prejudice of all kinds. To send that message may require continuing to work with some people whose views are actually abhorrent. Plus, there is always something to learn from the bad guys–even if it is only what they are thinking so that you know how to counter it better.

Although I have itemized several arguments against de-platforming people like Anna Netrebko (the soprano with the mixed political record), I am not sure where I ultimately stand on these matters. There is a case for refusing to work with individuals who hold odious views.

At first glance, it seems morally simpler to punish institutions for their odious policies than to punish individuals, such as sopranos, scientists, or Moscow apartment-owners. I have tried to apply this distinction when working with individual scholars from many countries, but not with or for their governments. However, the line between institutions and people is porous. Even a big bank is partly composed of small depositors. Even an individual scholar typically works for a state university. Even a free-thinking artist, like filmmaker Kirill Sokolov, may have taken government grants.

Turning to economic sanctions: they might work in this case, and they have the moral advantage of not directly killing people–as well as a lower risk of escalating to all-out or even nuclear war. However, for sanctions to succeed, they must inflict substantial hardship on a lot of people, including innocent civilians and even active opponents of the regime. It is much easier to rationalize causing economic hardship than using overt violence, even when the economic damage is devastating.

And sanctions may not work. If they don’t, then people like me who support them must take responsibility for the hardship. We mustn’t forget Yelena Balanovskaya and millions like her, including people in noncombatant countries like Afghanistan.

By the way, true dissidents and strong opponents of their own governments’ policies should welcome sanctions that affect themselves, so long as those efforts are likely to work. That may be true for the 85 Russian academicians who have signed the anti-war statement.

One possible solution is to focus as much as possible on the “oligarchs,” the Russian billionaires. They might have more leverage than other people (although the extent of their influence is debated); they are unlikely to suffer even if they lose a lot of money; and on the whole, their wealth has been ill-gotten in the first place. They are part of the problem, regardless of their opinions. Targeting oligarchs is central to the “Progressive Foreign Policy Response to the War in Ukraine,” which I find generally persuasive. As Henry Farrell says, perhaps sanctions that target the oligarchs can “be used to reshape the underlying systems of banking and finance that the current version of globalization relies on.”

But can we really target economic measures so that billionaires bear most of the cost, while also doing enough macroeconomic damage to affect the course of the war? I doubt it. Besides, we would want to influence oligarchs’ behavior, and that might (i suppose) require giving them a way out if they act better. In that case, what must an individual billionaire do to evade sanctions? Does one anti-war remark in English count, if it is hardly seen inside Russia? How about five anti-war social media posts in Russian? We are back to drawing lines across uneven terrain.

See also marginalizing views in a time of polarization; marginalizing odious views: a strategy