Last week, an altercation related to a “What is Gender?” event occurred in Speaker’s Corner – “a traditional site for public speeches and debates” in London.

The event was organized by a group self-identified “gender-critical feminists” – essentially, women who don’t believe that all women deserve equal rights.

As you might imagine, in the face of such an event a group of protestors showed up to demonstrate in favor of the opposite: all women deserve to be treated with dignity and respect.

From there, details begin to get fuzzy, but it appears that a woman from the first group – the “gender-critical feminists” – began harassing and attacking a woman from the second group – those supporting equality. The attacker was eventually pulled off the victim, getting clocked in the face in the process.

Afterwards, pictures of the attacker’s bruised face began to circulate online, along with a questionable story. The woman – who can be seen in a video to be shaking another woman like a rag doll until a third woman intervenes – claimed that she was the real victim; the other women attacked her.

Except, she didn’t say women.

“Gender-critical feminist” is a palatable label adopted by women more colloquially known as TERFs – Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminists. They are fervently passionate self-identified feminists whose feminism does not have space for all women.

In short, the attacker, having incited violence with seeming intention, proceeded to misgender her victims and successfully paint herself in popular media as just a normal old woman who was wrongly attacked while attempting to mind her own business.

This narrative is exceedingly dangerous.

Taken by itself, the event is unfortunate. Indeed, any time a person is attacked in the street is cause for concern.

But the narrative that emerged from this incident plays dangerously into broader misconceptions and stereotypes. It reinforces the idea that some women are inherently dangerous and that other women would be wise to distance themselves; it tacitly assumes that only some women are ‘truly’ women in some mystically vague sense of the word, while other women are not; and it erases and attempts to overlay the experience of women for whom these first two statements ring so obviously false.

It is gaslighting on a social scale.

Consider the account described in a statement by Action For Trans Health London, one of the organizations leading the demonstration against the TERFs:

Throughout the action, individuals there to support the ‘What is Gender?’ event non-consensually filmed and photographed the activists opposing the event. Often photos and videos taken by transphobes are posted online with the intention of inciting violence and harassment against trans activists. Due to this clear and documented history of transphobes violently ‘outing’ individuals of trans experience, visibility can be a high risk to trans individual’s personal safety.

During the action, a transphobe approached activists whilst filming with their camera. An individual then attempted to block their face from the lens of camera, leading to a scuffle between both individuals. This altercation was quickly and efficiently broken up by activists from both sides.

Action for Trans Health London later shared personal accounts from women who were assaulted by TERFs during the events of that evening.

Activists had good reason to be concerned for their safety.

Yet the stories emerging from that night don’t talk about the women who were assaulted. They don’t talk about the valid fear these women experienced when someone got up in their face with a camera. They didn’t talk about the pattern of violence and harassment these women face while just trying to lead their normal lives.

In fact, the stories do worse than ignore the incident all together. They blare the headline that a woman was hit during the altercation while reserving the full sense of ‘woman’ for the perpetrator; implicitly directing compassion to the person who did the attacking.

If you’re not familiar with the term, gaslighting is “a form of manipulation that seeks to sow seeds of doubt in a targeted individual or members of a group, hoping to make targets question their own memory, perception, and sanity.”

If you have never experienced gaslighting, be glad. If you have experienced gaslighting, you know that it is one of the worst possible sensations. You lose the ability to trust yourself, to trust your own instincts and senses. You lose the ability to know what is real due to the unwavering insistence of those around you that your reality is false.

And make no mistake, the dominant narrative emerging from the incident at Speaker’s Corner is a sophisticated form of gaslighting.

It is gaslighting when an attacker is allowed to mischaracterize their victims, it is gaslighting when the injuries suffered by an attacker are treated as more concerning than the injuries they inflicted, and it is gaslighting to pretend that people who have been systematically and zealously victimized are somehow the real perpetrators deserving of our scorn.

The sad truth is that there is an epidemic of violence against trans people. In the United States alone, at least 20 transgender people have been violently killed so far in 2017. Seven were murdered within the first six weeks of the year. Almost all were transgender women of color.

We cannot pretend that this violence isn’t occurring, and we cannot stay silent in the face of false narratives which wrongfully defame and mischaracterize an entire population of women.

I don’t know how to say it more plainly than that. To deny the rights of all women, to deny the existence of all women, and to deny the richly varied experiences of all women is simply unconscionable. You cannot do those things and call yourself a feminist.

I am not much of anyone, and it is always daunting to wonder what one small person can do in the face of terrible, complex, and systemic problems. I endeavor to do more, but literally the least I can do is to say this:

To all my transgender sisters: I see you. I believe you. And I will never, ever, stop fighting for you. I will not be silent.

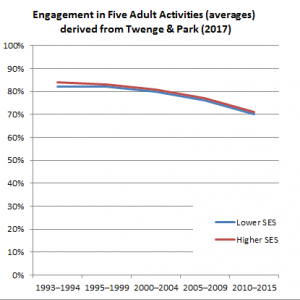

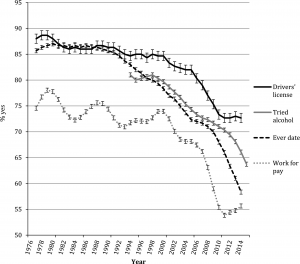

A new paper by Jean Twenge and Heejung Park (2017) is getting a lot of coverage. The main finding is a delay in the onset of certain activities traditionally defined as “adult.” This graph shows the trends in having a driver’s license, drinking alcohol (ever), dating, and working for pay–all down steeply for teenagers.

A new paper by Jean Twenge and Heejung Park (2017) is getting a lot of coverage. The main finding is a delay in the onset of certain activities traditionally defined as “adult.” This graph shows the trends in having a driver’s license, drinking alcohol (ever), dating, and working for pay–all down steeply for teenagers.