- People hold many morally relevant opinions, some concrete and particular, some abstract and general, some tentative and others categorical.

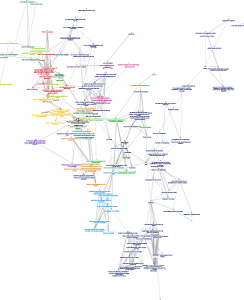

- People see connections–usually logical or empirical relationships–between some pairs of their own opinions and can link all of their opinions into one network. (Note: these first two theses are empirical, in that I have now “mapped” several dozen students’ or colleagues’ moral worldviews, and each person has connected all of his or her numerous moral ideas into a single, connected network. However, this is a smallish number of people who hardly reflect the world’s diversity.)

- Explicit moral argumentation takes the form of citing relevant moral ideas and explaining the links among them.

- The network structure of a person’s moral ideas is important. For instance, some ideas may be particularly central to the network or distant from each other. These properties affect our conclusions and behaviors. (Note: this is an empirical thesis for which I do not yet have adequate data. There are at least two rival theses. If people reason like classical utilitarians or rather simplistic Kantians, then they consistently apply one algorithm in all cases, and network analysis is irrelevant. Network analysis is also irrelevant if people make moral judgments because of unconscious assumptions and then rationalize them post hoc by inventing reasons.)

- Not all of our ideas are clearly defined, and many of the connections that we see among our ideas are not logically or empirically rigorous arguments. They are loose empirical generalizations or rough implications.

- It is better to have a large, complex map than a simple one that would meet stricter tests of logical and empirical rigor and clarity. It is better to preserve most of a typical person’s network because each idea and connection captures valid experiences and serves as a hedge against self-interest and fanaticism. The emergent social world is so complex that human beings, with our cognitive limits, cannot develop adequate networks of moral ideas that are clear and rigorous.

- Our ideas are not individual; they are relational. We hold ideas and make connections because of what others have proposed, asked, made salient, or provoked from us. A person’s moral map at a given moment is a piece of a community’s constantly evolving map.

- We begin with the moral ideas and connections that we are taught by our community and culture. We cannot be blamed (or praised) for their content. But we are responsible for interacting responsively with people who have had different experiences. Therefore, discursive virtues are paramount.

- Discursive virtues can be defined in network terms. For instance, a person whose network is centralized around one nonnegotiable idea cannot deliberate, and neither can a person whose ideas are disconnected. If two people interact but their networks remain unchanged, that is a sign of unresponsiveness.

- It is a worthwhile exercise to map one’s own current moral ideas as a network, reflect on both its content and its form, and interact with others who do the same.

Category Archives: moral network mapping

the advantages and drawbacks of precision in ethics

I like to ask people to state their own beliefs that are relevant to ethics and then draw connections among those ideas to create networks that represent their moral worldviews. I put people (students and others) in dialogue with each other, invite them to explain their networks to peers, and watch connections form.

I like to ask people to state their own beliefs that are relevant to ethics and then draw connections among those ideas to create networks that represent their moral worldviews. I put people (students and others) in dialogue with each other, invite them to explain their networks to peers, and watch connections form.

Usually the ideas that people propose are not precise. In explaining what we believe, we don’t employ many terms that we could define with necessary and sufficient conditions, nor do we often use quantifiers like “all” or “exactly one.” The connections we detect among our ideas are rarely logical inferences. They are looser links: resemblances, rough implications, empirical generalizations.

One impulse is to strive for as much precision as possible. That is a fundamental goal of analytic moral philosophy and it has significant merit. If someone proposed, “We should strive to improve everyone’s lives,” I would join mainstream analytic philosophers in requesting more clarity. Does that mean maximizing net human welfare? Does “welfare” mean happiness, satisfaction, or objective well-being? Does it trade off against freedom and autonomy? Does “everyone” mean all currently living human beings? (What about future generations?) Does “strive” mean actually maximize net welfare, or have a generally beneficent attitude toward others? These are valid and hard questions.

On the other hand, if the goal is descriptive moral psychology, it is a mistake to ask for that level of precision. We all hold–and are motivated by–rougher moral ideas and looser connections than could pass muster with an analytical philosopher. If you want to know what people believe, you must model those ideas and relationships as well as the clear ones. If you encourage people to map out many of their ideas and relationships, they will produce complex and elaborate networks that are useful for representing their mentalities and for provoking reflection.

That still leaves the normative question: how much precision should each of us strive for? I would say some but not too much. One of my favorite quotes is from Bernard Williams, in Ethics and the Limits of Philosophy (1985, p. 117): “Theory typically uses the assumption that we probably have too many ethical ideas, some of which may well turn out to be mere prejudices. Our major problem now is actually that we have not too many but too few, and we need to cherish as many as we can.”

I’d expand that remark as follows: Through direct and vicarious experience, we build up collections of moral ideas that give our lives meaning and restrain our basest instincts. We also connect our ideas; we say that we believe A because it seems somehow related to B. If we must pass all these ideas and connections through a screen for clarity, precision, and inferential rigor, most will have to go. That will leave us with less meaning and less constraint against mere inclination and will.

Seeking clarity can illuminate. It can, for instance, force us to disaggregate a vague idea into a set of related ideas that are worth seeing on their own. Or it can reveal gaps and tradeoffs that deserve consideration. Formal philosophy is also useful for developing specific ideas that are clear and precise and that relate to one another logically.

However, it is a false dream that we can convert our entire networks of moral ideas into structures of clearly defined concepts and implications. Even the best moral arguments carry just a short distance–from a premise to a conclusion, or maybe as far as another conclusion or two, but not all the way across the domain of the moral. It is good to have a dense, complex, and expansive network of ideas that draws on experience and demands constant reflection and reevaluation, even if its components are a bit vague and the links are hard to articulate. Better that than a crystalline chain of reasons that connects just a few ideas and leaves us otherwise free to be selfish or fanatical.

Selim Berker on moral coherence

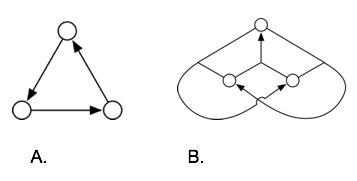

In “Coherentism via Graphs,”[i] Selim Berker begins to work out a theory of the coherence of a person’s beliefs in terms of its network properties. Consider these two diagrams (A and B) borrowed from his article, both of which depict the beliefs that an individual holds at a given time. If one beliefs supports another, they are linked with an arrow.

Both diagrams show an individual holding three connected and mutually consistent beliefs. Thus traditional methods of measuring coherence can’t differentiate between these two structures. However, Graph A is pretty obviously problematic. It involves an infinite regress—or what has been called, since ancient times, “circular reasoning.” Graph B is far more persuasive. If someone holds beliefs that are connected as in B, the result looks like a meaningfully coherent view. If you find coherence relevant to justification, then you will have a reason to think that the beliefs in B are justified—a reason that is absent in A.

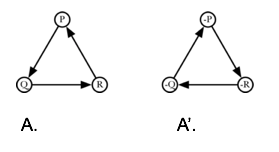

Berker also proposes a subtler but more decisive reason that B is better than A. Below I show A again, now with the component beliefs labeled as P, Q, and R. If the law of contraposition holds, than A implies another graph, A’, that is its exact opposite. A’ includes beliefs -P, -Q, and -R, and the arrows point in the reverse direction.

But that means that if belief P is justified because it is part of a coherent system of beliefs, then the same must be true of -P, which is absurd.[ii]

The overall point is that coherence is a property of the network structure of beliefs. That should be interesting to coherentists, who argue that what justifies any given belief just is its place in a coherent system. But it should also be interesting to foundationalists, who believe that some beliefs are justified independently of their relations to other ideas. Foundationalists still recognize that many, if not most, of our beliefs are justified by how they are connected to other beliefs. Thus, even though they believe in foundations, they still need an account of what makes a worldview coherent.

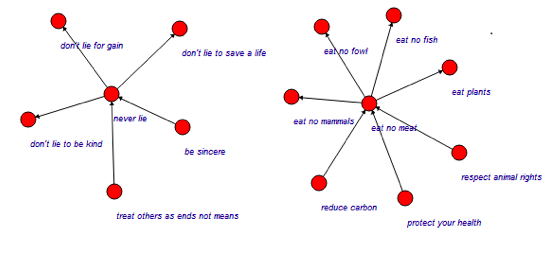

I have been developing a similar view, with a narrower application to moral thought (and without Berker’s deep grasp of current epistemology). I am motivated, first, by the sense that what makes a moral worldview impressively coherent cannot be seen without diagramming its whole structure. Imagine, for instance, a person who holds two major moral beliefs: “Never lie” and “Do not eat meat.” Assume that this person has not found or seen any particular connection between these two main ideas.

His or her set of maxims is perfectly consistent: there is no contradiction between any two nodes. And every idea has a connection to another. But if we wanted to judge the coherence of this worldview, we would not be satisfied with knowing the proportion of the components that were consistent and directly connected. It would matter that the person holds two separate clusters of ideas—two hubs with spokes. This person’s network is fairly coherent insofar as it is organized into clusters rather than being completely scattered; but it would be more coherent if the two clusters interconnected via large integrating ideas. You can’t see the problem without diagramming the structure.

I also have another motivation for wanting to explore moral worldviews and political ideologies as networks of beliefs. In moral philosophy and political theory, constructed systems are very prominent. Although diverse in many respects, such systems share the feature that they could be diagrammed neatly and parsimoniously. In utilitarianism, the principle of utility is the hub, and every valid moral judgment is a spoke. That theory is so simple that to diagram it would be trivial. Kantianism centers on several connected principles, and Aristotelian, Thomist, and Marxist views are perhaps more complicated still. But in every case, a network diagram of the theory would be organized and regular enough that the whole could be conveyed concisely in words.

In contrast, my own moral worldview has accumulated over nearly half century as I have taken aboard various moral ideas that I’ve found intuitive (or even compelling) and have noticed connections among them. My network is now very large and not terribly well organized. A narrative description of it would have to be lengthy and rambling. Many of my moral beliefs are nowhere near each other in a network that sprawls widely and clusters around many centers.

I suspect this condition is fairly typical. No doubt, individuals differ in how large, how complex, and how organized their moral worldviews have become, but a truly organized structure is rare. (I have asked a total of about 60 students and colleagues to diagram their own views, and only one of the 60 gave me a network that could be concisely summarized.) That means that such constructed systems as Kantianism and utilitarianism are remote from most people’s moral psychology.

Further, I think that having a loosely organized but large and connected network is a sign of moral maturity. It is a Good Thing. That is obviously a substantive moral judgment, not a self-evident proposition. It arises from a certain view of liberalism that would take me more than a blog post to elucidate. But the essential principle is that we ought to be responsive to other people’s moral experiences.

Berker includes experiences as well as beliefs in his network-diagrams of people’s worldviews.[iii] In science, it should not matter who has the experience. An experience of a natural phenomenon is supposed to be replicable; you, too, can climb the Leaning Tower and repeat Galileo’s experiment. But in the moral domain, experience is not replicable or subject-neutral in the same way. Since I am a man, I cannot experience having been a woman my whole life so far. Thus vicarious experiences are essential to moral development.

If we are responsive, we will accumulate sprawling and random-looking networks of moral beliefs as we interact with diverse other people. These networks can be usefully analyzed with the techniques developed for analyzing large biological and social networks. It will be illuminating to look for clusters and gaps and for nodes that are more central than average in the structure as a whole. The coherence of such a network is not a matter of the proportion of the beliefs that are consistent with each other. Its coherence can better be evaluated with the kinds of metrics we use to assess the size, connectedness, density, centralization, and clustering of the complex networks that accumulate in nature.

On the other hand, if someone adopts a moral view that could be diagrammed as a simple, organized structure, he has not been responsive to others so far and he will be hard pressed to incorporate their experiences in the future. At the extreme, his simple graph is a sign of fanaticism.

See also: envisioning morality as a network; it’s not just what you think, but how your thoughts are organized; Stanley Cavell: morality as one way of living well; and ethical reasoning as a scale-free network (my first thoughts along these lines, from 2009).

Notes

[i] Berker, S. (2015), Coherentism via Graphs. Philosophical Issues, 25: 322–352. doi: 10.1111/phis.12052

[ii] “Coherence, we have been assuming, is a matter of the structure of support among a subject’s beliefs, experiences, and other justificatorily-relevant mental states at a given time.” But we can use directed hypergraphs (in mathematics, networks in which any of the nodes can be connected to any number of the other nodes by means of arrows) to represent all of those support relations. That is, we use directed hypergraphs to represent all of the relations that have a bearing on coherence. It follows that coherence is itself expressible as a graph-theoretic property of our directed hypergraphs (p. 339).

[iii] “Many theorists hold that a subject’s perceptual experiences are justificatorily relevant (in these sense that they either partially or entirely make it the case that the subject is justified in believing something).”

network dynamics in conversation

(Dayton, OH) It is in conversations–face-to-face or virtual, oral or written, small or massive, formal or informal–that we form our views of public issues, hold ourselves accountable for our reasons and actions, check our assumptions, expand our horizons, gain the satisfaction of being recognized, display eloquence, and develop enough will to act together.

Some conversations are better than others, and we need to understand more about the differences. I think that mapping conversations as evolving networks is a promising strategy. At least three relevant phenomena can be modeled in network terms:

- As we discuss, we collaboratively construct networks of ideas. I say that I favor marriage equality because adults who love and commit to each other should have the protection of law, and because people should be treated equally regardless of sexual orientation. In those sentences, I have put several ideas together into a structure. You can add to my structure by posing other ideas, whether they connect to mine or conflict with mine. The group’s epistemic network expands and changes as we talk.

- We also form and change social networks during a discussion. The nodes in a social network are people, and the links between pairs of people can be characterized by knowledge, trust, respect, affection, etc (or their opposites). People who converse may already belong to the same social networks. Their discussions may develop and alter their social networks.

- We make “meta” comments about the conversation. For instance, I might ask you to clarify what you meant when you said P. Or I might say I agree with you, or withdraw my comment, or propose that the truth lies between what I said and that you said. These are interesting moments because they are about both the epistemic and the social network that already exists, and they can affect those networks. In an important 1983 article, Berkowitz and Gibbs called them “transacts” and found they led to learning when children used them.

Consider some subtle cases and how they might be modeled in network terms.

- Person A only cares about influencing her boss, B, who sits at the head of the table, but she chooses to turn toward everyone else in a meeting and address them. In social network terms, her talk is literally directed at a whole set of peers, but there is a more significant network connection between her and just one other person.

- A says P, and B pays no attention because B thinks that A is a fool. C says P, and B agrees with it because B thinks that C is smart. In this case, the social network affects the epistemic network.

- A wants B to like her, so she withdraws point P that she had made earlier because B objected to it. With that concession, the social network changes in one way, the epistemic network in a different way. B says, “I appreciate your flexibility, but really, you should insist on what you believe.” B’s meta-comment puts P back on the epistemic map and affects the social network.

In technical terms, I’d measure the epistemic network by representing transcripts of discussions as ideas and links (the links being arguments of various kinds) and probably locating the nodes on a two-dimensional plane that reflect key dimensions of disagreement in the conversation. I’d watch the network change as the participants talk.

I’d measure social networks by asking people to characterize the ties between them and each of the other participants, before and after the discussion.

Finally, I might model the relevant personal beliefs of each participant before and after a discussion as a network of ideas and links, which I would derive from a private interview or short essay. I would be interested in how much of the private network ends up in public and how much the public discussion affects the private network.

The point of all this measurement is to provide data that is useful for evaluative judgment. So the normative questions (“What makes a good discussion?” “How should you participate in discussions?”) are central. I think they deserve more exploration than we have had so far, although philosophers have certainly contributed criteria.

For instance, Jurgen Habermas wrote that in an ideal discussion, “no force except that of the better argument is exercised” (Habermas 1975, p. 108). He would want an epistemic network composed of objectively defensible ideas and links to influence the participants, completely independent of their places in a social network. Just because everyone knows and admires A but dislikes B, it doesn’t mean that people should absorb A’s ideas and ignore B’s ideas.

Another example: Olivia Newman argues that a good discussion in a liberal democracy won’t produce a single hierarchical framework of ideas, but will rather encompass numerous clusters of ideas that are only loosely connected. That shape reflects value pluralism while still allowing mutual learning. Thus a group’s epistemic network should be clustered but not overly centralized.

We might add that good discussants should continue to add new nodes and connections as long as the conversation continues (not repeat points already made); that

See also a method for mapping discussions as networks and assessing a discussion.

on philosophy as a way of life

(San Antonio, TX) Here I briefly introduce schools of thought–Indian and European–that have combined introspective mental exercises with reasoning about moral principles and critical analysis of social systems. I contrast their integrated approach to forms of philosophy that construct comprehensive models of ethics by using reasons alone. This essay will be the introduction to a book on mapping moral networks, which is a new introspective exercise.

–“I should have given that man some change. He looked hungry.”

–“He would have used it for drugs or alcohol.”

–“Maybe he has that right—it’s his life!”

–“If you’re going to try to help the homeless, you should donate to the Downtown Shelter. They spend the money on real needs. Plus, it’s tax-deductible.”

–“That’s not realistic advice. While I am talking to a homeless person, I have homelessness on my mind. Once I get back home, the thought is gone. I’d never remember to mail off a check.”

–“Perhaps we should set aside some time every day to practice compassion and remember people who are suffering.”

–“Yes, I guess I’m for compassion—but handing someone money seems to create the wrong kind of relationship. What did Emerson write? ‘Though I confess with shame I sometimes succumb and give the dollar, it is a wicked dollar which by and by I shall have the manhood to withhold.’”

–“Maybe we should think about why some people are homeless in the first place and what policies would end that situation.”

This little dialog shows a pair of human beings doing several valuable things. They display emotions, some expressed with enthusiasm and some with regret. They exchange reasons. But they know that their reasons may not actually influence them deeply because they have habits that they would have to counteract by altering their regular routines. They cite rules—such as the tax deduction for charity and the shelter’s ban on alcohol—that are meant to improve and regulate people’s behavior. Finally, one speaker (perhaps showing off) cites an influential thinker from the past whose argument seems relevant.

Each of these modes of thought can be practiced at a high level. Instead of quickly asserting moral beliefs, we can develop whole arguments: chains of reasons that carry from a premise to a conclusion. If the argument persuades, it joins the list of things you believe, and you have been changed. Anyone who is serious about being a good person must struggle to get the reasons right and then act according to the conclusions.

But because our wills are weak, we also need enforced rules that guide or constrain us. And just as we can reason about our own choices (“Should I give a dollar to this homeless person?”), so we can reason about laws, regulations, social norms, and institutions. We can ask whether the rules that are in place are acceptable and, if not, how they should change. As Alexander Hamilton wrote on the first page of the Federalist Papers, laws are meant to arise from “reflection and choice” rather than “accident and force.” Political thinkers have often offered elaborate arguments about how institutions should be designed to improve people’s behavior.

Meanwhile, we can learn reflective practices such as confession, memorization, visualization, meditation, autobiographical reflection, and prayer. These methods are more personal than arguments, for they work directly on an individual’s beliefs, emotions, and habits. They are less coercive but more individualized than rules and laws, for we enforce these practices on ourselves. They tend to require practice and repetition to achieve their goals. You can read an argument once in order to evaluate it, but you must repeat a mental exercise for it to affect your psychology. In the 1500s, Michel de Montaigne observed, “Even when we apply our minds willingly to reason and instruction, they are rarely powerful enough to carry us all the way to action, unless we also exercise and train the soul by experience for the path on which we would send it” (II.6). But self-discipline without reason is blind, potentially turning us into worse rather than better people. Think of terrorists who have overcome their habits of peacefulness and tolerance to make themselves into killers; their fault is not a lack of discipline but a poor choice of means and (often) ends.

Finally, we can take the interpretation of other people’s thoughts to high levels of sophistication and rigor. Instead of just quoting a snippet of Emerson, we can make a full study of his ideas in their context. Cultural critique and intellectual history help us understand where we come from and what influences us. After all, we believe what we do in large measure because other people have formed and shaped our thoughts. No one invents her whole worldview from scratch. Since we begin with the traditions that have developed so far, it is important to understand them. Reasoning or self-discipline requires a critical understanding of the materials with which we construct our thoughts, which are ideas that our predecessors have invented.

It makes sense to put these modes together because we are reasonable creatures (capable of offering and sharing reasons for what we do), but we are also emotional and habitual creatures (requiring either external rules or mental discipline and practice to improve ourselves), political creatures (living in communities structured by laws and norms that people make and change), and historical creatures (shaped by the heritage of past thought).

In some periods, it has been common to combine argumentation about personal choices and social institutions, mental exercises, and the critical study of past thinkers. In other times–including our own–these elements have come apart. Here I will offer a very short and suggestive review of that history to support the thesis that now is a time to put the pieces back together.

Plato and Aristotle, the preeminent philosophers of the Greek classical era, each offered a whole system of thought. Think of an argument as a persuasive connection among two or more ideas. Plato and Aristotle offered arguments, but not just a few disconnected ones. They tried to build whole structures of arguments that would cover most of the important topics for human beings and lead the reader from self-evident premises to sometimes unexpected conclusions. The most ambitious goal for that kind of systematic thought is that it can really settle matters of importance and change people’s lives by giving them whole integrated worldviews that are genuinely persuasive. One source of persuasiveness is coherence; the whole system impresses us by hanging together so well.

Platonism and Aristotelianism are “designed” systems in the sense that the authors try to build complete and self-reliant structures with as few assumptions as possible. A systematic philosopher is like an engineer or architect responsible for the blueprints of a whole structure, not like a gardener who prunes and tends the plants that have already grown on a plot of land– nor like a traveler, observing and assessing the ways of diverse people. To endorse a systematic philosophy is to adopt the whole blueprint as the structure of one’s own thought. Of course, systematic philosophers do not view themselves as creating ideas but rather as discovering truths: their models are meant to represent the way the world actually is. They see themselves less as engineers than as physicists, creating models of truth. And one of them could be right–but only one, for the rest would have to be in error. If you doubt that a given philosophy is an accurate representation of truth, then it seems rather to be a carefully and intentionally designed structure, a human product.

The followers of Plato and Aristotle organized “schools,” known respectively as the Lyceum and the Academy, that maintained their founders’ traditions of systematic philosophy. But after Aristotle’s death, philosophy in the Mediterranean region tended to retreat from those ambitions. New schools arose called Stoicism, Epicureanism, and Epicurianism that had a different character. Sextus Empiricus was a member of the Skeptical school who lived in the Roman period. He explained that Skeptics did not offer a whole set of beliefs that were consistent with each other, consistent with what we observe about the world, and leading to counterintuitive conclusions. (He didn’t name Plato or Aristotle in this passage but must have had them in mind.) However, Sextus continued, a Skeptic did offer a method that helped people to live rightly. (Outlines of Pyrrhonnism, 1.8.16). The main practice of the Skeptical school consisted of going over examples that would shake a person’s confidence in general truths. For instance, recognizing that people from different nations believed different things would prevent a Skeptic from fruitlessly searching for truths beyond human ken. “Consideration of our differences leads to suspension of judgment,” Sextus wrote; and suspending judgment was a path to inner peace and good treatment of others.

Sextus believed he was offering a persuasive argument: if human beings believe radically different things, none is likely correct. But this was not part of an elaborate system of arguments linking many ideas together. Instead, it was a fairly simple thought meant to change our mental habits so that we would live better. Such thoughts had to be repeated as a daily practice to change people’s psychologies. For instance, you could gain mental peace or equanimity by reflecting daily on the impossibility of attaining certain knowledge of a wide range of topics.

Epicurus (341–270 BCE) founded the school that bore his name. His “Letter to Menoeceus” includes a formal argument that we should not fear death. Death is a lack of sensation, so we will feel nothing bad once we’re dead. To have a distressing feeling of fear now, when we are not yet dead, is irrational. The famous conclusion follows logically enough: “Death is nothing to us.” But Epicurus knows that such arguments will not alone counteract the ingrained mental habit of fearing death. So he ends his letter by advising Menoeceus “to practice the thought of this and similar things day and night, both alone and with someone who is like you.” The main verb here could be translated as “exercise,” “practice,” or “meditate on.” It is a mental practice that anyone can use, regardless of her other beliefs and assumptions. Importantly, it should be pursued both singly and as part of a community. (Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, 10: 134. The verb is meletao, translated into Latin as meditatio.)

The late French historian Pierre Hadot argued that members of the Hellenistic schools were most interested in these reflective practices. Hadot called their style “Philosophy as a Way of Life.” Hadot claimed that we misread a work like Marcus Aurelius’ Meditations if we assume that it is a set of conclusions backed by reasons. Instead, we should find there a record of the Stoic emperor’s mental exercises, beginning with his daily thanks to each of his moral teachers. Marcus Aurelius listed these exemplary men by name because he would actually visualize each one every day. The Meditations shows us how a Stoic went about meditating.

Although Hadot emphasized the reflective practices of the Hellenistic schools, Stoics, Epicureans, Skeptics and and others also took formal reasoning very seriously (Nussbaum, The Therapy of Desire, p. 353) and they rigorously studied older works, including those of Plato and Aristotle, from which they borrowed specific ideas, if not the overall structures. In short, they combined at least three of the four modes of thought that seem essential to moral improvement. Their weakest contribution was in the area of political and legal critique. They did contribute some political ideas, but on the whole, they were alienated from politics and pessimistic about improving institutions. For many of them, the only truly satisfactory regime had been the self-governing city-state of classical Greece, which was now obsolete.

The same Greek word that we translate as “school” was also used for the Jewish sects of the same time, the Pharisees and Sadducees. And the Greco-Roman schools of this time were roughly similar to Asian traditions, which also produced organized bodies of living teachers and students who studied their own communities’ foundational texts. One could join the Skeptics or Stoics almost as one could join a Hindu philosophical tradition or a Buddhist sangha. In the Bhagavad Gita, Krishna says:

Simpletons separate philosophy [sankhya, or organized theoretical inquiry]

from discipline [yoga], but the learned do not;

applying one correctly, a man finds the fruit of both.(Fifth Teaching, 4-5, translated by Barbara Stoler Miller and slightly edited)

The man whom we call the Buddha also mixed philosophical argument with reflective practices. Our evidence of his own thought is so indirect that many interpretations are plausible. One view is that the Buddha was educated in a culture that had developed elaborate, systematic moral philosophies in the form of the Vedic texts. But the Buddha was not convinced that these systems were helpful for the sole purpose that mattered to him: improving human life. His apparent skepticism is captured in anecdotes like the one in which he is asked whether gods cause suffering, and he says that that’s like asking who shot a poisoned arrow during a battle: the point is to get the arrow out of the victim. In lieu of a systematic philosophy, the Buddha proposed four main conclusions, each of which he supported by reasons and experience: the truth of suffering, the truth of the cause of suffering, the truth of the end of suffering, and the truth of the path that leads to the end of suffering. These four ideas were not meant to be comprehensive, nor would assenting to them at a theoretical level improve one’s life; to accomplish that would require repeated mental practices.

The Buddha’s world was not unlike the milieu of Plato and Aristotle, but the two intellectual traditions were still fairly remote while these men lived. That situation changed when Aristotle’s pupil, Alexander the Great, conquered northern India and left an empire to Greek successors. For instance, Strato I ruled territories around Punjab; his coins showed Athena (the goddess of wisdom) with Greek text on one side, and “King Strato, Savior and of the Dharma” in an Indian script on the reverse. It was in this Greco-Indian context that the early Buddhists developed their ideas, not only offering mental exercises–such as yoga–but also practicing formal argumentation and textual criticism. As this example illustrates, any distinction between Western (or European) and Eastern (or Asian) philosophy is largely confusing; both traditions have encompassed enormous diversity, and the two have often overlapped, as in the centuries after the deaths of Aristotle and Buddha.

Hadot claimed, however, that medieval Christianity ruptured the combination of argument and mental exercise that had been common in both the Mediterranean and in Northern India before the Christian Era. Medieval Christians adopted all the major ideas of the classical moral thinkers but parceled them out. Abstract reasoning and the interpretation of ancient texts went to the university, where knowledge became the end. Meanwhile, reflective practices were taught to monks and laypeople to be used without elaborate argumentation. A typical monk fasted, sang, and recited prayers but was not expected to reason about theological or moral principles. Hadot argued that this split was fateful and still predominates today, “In modern university philosophy, philosophy is obviously no longer a way of life or form of life unless it be the form of life of a professor of philosophy.”

The best illustration of Hadot’s thesis is the High Middle Ages of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries in Western Europe. That period generated Scholastic theology, an impressive effort to explain everything in terms of organized and coherent principles that derived from scripture and Aristotle’s philosophy. The mode of Scholastic philosophy was abstract argumentation illustrated with examples and authoritative quotes. Its origin was in universities, and its leading lights were university teachers. St. Thomas Aquinas, for example, taught at the University of Paris. At the very beginning of his multi-volume book aimed at non-Christians, Aquinas defined the “wise person” as “one whose consideration is directed at the end [or ultimate purpose] of the universe, which is identical to the origin of the universe; that is why, according to The Philosopher [Aristotle], it is the job of the wise one to consider the highest causes” (Summa Contra Gentiles, I.i). From that start, Aquinas developed a whole theory of everything important. He assumed that if we could only answer the most general and abstract questions correctly, we could derive every important truth and law from those answers, and thereby persuade even heretics and atheists by force of reason alone. This project had relatively little to do with prayer, confession, meditation, pilgrimage, and penance, although those activities were also raised to high arts in the same era.

Although “philosophy as a way of life” was marginal in the high middle ages, the Renaissance thinkers whom we call humanists rediscovered the Hellenistic schools and their approach to improving concrete human thought and behavior. Montaigne, a great representative of Renaissance humanism and a man deeply immersed in the Hellenistic schools, relished listing the enormous diversity of human customs and beliefs–just as the Skeptic Sextus Empiricus had recommended. This diversity led Montaigne to doubt all elaborately designed theories about good and evil. He wrote that “the laws of conscience” (which tell us what is right and wrong) are not actually natural and universal, as we assume. They are rather born of “custom.” We “inwardly venerate” the manners and opinions approved by the people immediately around us, thinking they are true even though they merely reflect our community’s customs (1.23). The same must be true of abstract philosophical reasons; they are not universal or certain but rather derive from local mores. We believe what we happen to believe because of where we were born and who educated us.

But we can look critically within. Montaigne wrote introspective prose texts that he called “attempts” (in French, essais), from which we derive the word “essay.” His “essays” were not arguments about what is right and good for all people, but records of his struggle to understand and improve himself:

For, as Pliny says, each person is a very good lesson to himself, provided he has the audacity to look from up close. This [the book of Essays] is not my teaching, it is my studying; it is not a lesson for anyone else, but for myself. What helps me just might help another. … It is a tricky business, and harder than it seems, to follow such a wandering quarry as our own spirit, to penetrate its deep darknesses and inner folds. …This is a new and extraordinary pastime that withdraws us from the typical occupations of the world, indeed, even from the most commendable activities. For many years now, my thoughts have had no object but myself; I investigate and study nothing but me, and if I study something else, I immediately apply it to myself–or (better put) within myself. … My vocation and my art is to live (ii.6).

Montaigne said that he studied only himself, but he was evidently fascinated by other people’s individual personalities and characters as well. The aspect of his work that I want to bring out here is not so much its inward turn as its particularity. Montaigne tried to improve a specific person (who happened to be himself), and he assumed that this effort would require concentrated inspection and reflection. He did not propose a unified theory of the self, comparable to theories that explain all of human psychology in terms of self-interest, or reason struggling to master passion, or some other small set of principles. He rather saw his own personality as a somewhat miscellaneous assemblage of beliefs and mental habits that he had accumulated over a lifetime. He turned to one belief or emotion at a time, identifying and describing it and sometimes seeking to change it. He doubted that large abstract principles would be much help in this ongoing effort. He was less like an engineer or architect than a gardener working on an old and somewhat untidy plot of land.

Montaigne was relatively secular, but a similar shift can also be found in deeply religious authors of the same period, such as St. Francis Xavier and St. Teresa of Ávila, each of whom reunited reasoning and argumentation with continuous introspection and techniques of mental discipline. Thus–to be clear–the split between abstract reasoning and mental self-discipline is not intrinsic to Christianity; it is just one trend in Christian history that has waxed and waned over two millennia.

Systematic philosophy was rekindled when Immanuel Kant awoke from what he called his “slumbers” to produce an impressively organized worldview that influenced and inspired efforts by Schiller, Hegel, and Marx, among others. Despite their vast differences, the great German philosophers of 1750-1850 all hoped to construct coherent theories that would yield guidance for all human beings. They were intensely concerned with politics, law, and institutions as well as personal choices. In these respects, at least, they were comparable to Plato and Aristotle. But once that moment of confidence ended, intellectual leadership again passed to essayists who were most interested in individual characters (their own or other people’s) and who tried idiosyncratic “experiments in living”–people like Nietzsche, Thoreau, and Emerson. All three of these writers admired the ancient Stoics and classical Indian thinkers, and like them, tended to withdraw from politics, pessimistic that they could change it for the better.

Somewhat later, Hannah Arendt (1906-1975) exemplified a new combination of argumentation, self-discipline, and cultural critique–and she added a strong dimension of political activism. When she was a young woman, Arendt had studied with the most distinguished representative of academic German philosophy then alive, Martin Heidegger. Many years later, she recalled:

The rumor about Heidegger put it quite simply: Thinking has come to life again. … People followed the rumor about Heidegger in order to learn thinking. What was experienced was that thinking as pure activity–and this means impelled neither by the thirst for knowledge, nor the drive for cognition–can become a passion which not so much rules and oppresses all other capacities and gifts, as it orders them and prevails through them. We are so accustomed to the old opposition of reason versus passion, spirit versus life, that the idea of passionate thinking, in which thinking and aliveness become one, takes us somewhat aback.

What did her phrase “Thinking has come to life again” mean? Because Heidegger wrote a book (Being and Time) that seems comparable to the grand systematic, theoretical works of Kant, Hegel, and Marx, one might assume that Arendt was merely acknowledging her former teacher’s importance. Perhaps she meant that Heidegger was famous and impressive, and it was exciting to be able to study with him.

But I think she meant something different. Reading classical works in Heidegger’s seminar (or in a reading group, called a Graecae) was a creative and spiritual exercise. The point was not only to construct arguments but to live a new kind of life in a community of fellow seekers. Once Arendt broke off her intellectual (and romantic) relationship with Heidegger, she moved to the seminar of Karl Jaspers. Jaspers had been a brilliant psychiatrist, and he saw philosophy as a different kind of therapy, better than psychiatry because it aimed at moral improvement instead of mere mental health. Elisabeth Young-Bruehl cites this sentence of Jaspers’ as exemplary: “Philosophizing is real as it pervades an individual life at a given moment.” Young-Bruehl adds: “For Hannah Arendt, this concrete approach was a revelation; and Jaspers living his philosophy was an example to her: ‘I perceived his Reason in praxis, so to speak,’ she remembered.”(Young-Bruehl, Hannah Arendt: For Love of the World, 63-4.)

At the very beginning of her career, Arendt was not particularly interested in politics–but politics was interested in her, a Jewish woman from a leftist family who lived a bohemian life. Already subject to discrimination, she became an enemy of the state with the Nazi takeover of 1933. By then she had decided that pure introspection was self-indulgent and that Heidegger’s philosophy was selfishly egoistic. She found deep satisfaction in what she called “action,” assisting enemies of the regime to escape and then escaping herself. From then on, she sought to combine “thinking” (disciplined inquiry) with political action in ways that were meant to pervade her whole life. But like the other skeptical authors I have cited so far, she offered no system; rather a set of practices that would improve the women and men of her own time.

By the time of Arendt’s death in 1975, systematic moral philosophy was being revived in the English-speaking world. The Harvard philosopher John Rawls proposed an ambitious new theory of justice that triggered valuable responses from libertarians and others. Kant and Aristotle were among Rawls’ explicit influences and models. But skepticism about such grand theories seems to have returned since the 1990s; indeed, Rawls’ own late work was more modest than his A Theory of Justice (1971).

I have suggested a rough pattern of oscillation between periods when leading thinkers are confident about philosophy as systematic reasoning–and times when influential writers turn instead to concrete exercises of reflection. During moments of maximum confidence about pure and self-sufficient reasoning, the two classical Greek theorists, Plato and Aristotle, typically become inspirations, even for philosophers who disagree with their actual views. In the periods of greater skepticism, authors frequently turn back to the Hellenistic Schools of the Mediterranean, to their analogues in India, or to the subsequent movements that they have inspired.

In these skeptical moments, authors begin by identifying what specific individuals happen to believe and reflect on these emotions and ideas, one at a time. The results are often admirable. However, when mental exercises come unmoored from reasoning and from political engagement, the risk of self-indulgence arises. Thus I am not proposing that we renounce argumentation in favor of introspection and mental hygiene, but rather than we combine them again–and add a strong element of cultural and political critique. This combination seems essential if are to avoid giving up altogether on improving ourselves and the world around us.

The situation is not immediately promising. The academic discipline of moral philosophy is again dominated by an argumentative mode that doesn’t take seriously mental exercises and practices. Academic philosophers analyze and sometimes develop reasons; they do not offer or even study practices. Thoreau’s exclamation in Walden rings true today, “There are nowadays professors of philosophy, but not philosophers.” He explained, “To be a philosopher is not merely to have subtle thoughts, nor even to found a school, but so to love wisdom as to live according to its dictates. … It is to solve some of the problems of live, not only theoretically, but practically.”

Outside the academy, mental exercises are common, given the continued importance of prayer and the rising popularity of meditation in the West. The self-help section of a bookstore is full of works on these topics and memoirs of individuals who have tried radical experiments in living, from renouncing all their worldly goods to moving to Tuscany. But for many people, meditation and other forms of mental discipline are separate from formal argumentation and moral justification, not to mention social critique. In fact, we are sometimes told that meditation is an opportunity to leave moral judgment behind for a time.

Meanwhile, “therapy”—the Greek word for what Hellenistic philosophers offered–has been taken over by clinical psychology. That discipline does good but misses the ancient objectives of philosophy. Modern therapy defines its goals in terms of health, normality, or happiness (as reported by the patient). Therapy is successful if the patient lacks any identifiable pathologies, such as depression or anxiety; behaves and thinks in ways that are statistically typical for people of her age and situation; and feels OK. Gone is a restless quest for truth and rightness that can upset one’s equilibrium, make one behave unusually, and even bring about mental anguish.

It would be false as well as arrogant to recommend present this book as a momentous new beginning. There have in fact been many examples of efforts to unite reasoning about moral choices and about institutions, mental discipline, and the interpretation of past thought. I have already mentioned Epicurus and Sextus, the Buddha, Montaigne, Nietzsche, Thoreau, Emerson, and Arendt as models and will add more as the book proceeds. These authors vary enormously, not only in their actual beliefs but in their genres and styles of writing. Montaigne invented the introspective essay, which was also Emerson’s main form; but Nietzsche wrote aphorisms, Thoreau reported on his radical experiment with a new form of life, and we attribute to the Buddha texts that we call “sermons.” I intend homage to these authors both when I quote them and when I propose a new experiment.

The experiment begins with a few modest assumptions. You already have many beliefs relevant to moral judgment that you have derived from forebears and peers or invented or discovered yourself. At least some of these beliefs seem to you to be connected to other beliefs by reasons. Thus you could view your whole moral mentality as a network. A network is a contemporary model for thinking about the “deep darknesses and inner folds” that Montaigne found as he explored his self. Thinking in terms of networks is useful because we now have illuminating methods for network-analysis.

A systematic moral philosophy proposes one organized network composed of ideas linked by reasons. Its organization is typically hierarchical, with one of a few big ideas implying all the others. The systematic approach suggests that you should adopt this ideal network, wholesale, to replace whatever ideas you have accumulated. I would reply: if there is one ideal, complete, and valid network of moral ideas, we have no way of knowing what it looks like. Instead, we each have a different structure of ideas and connections in our own heads. But we can improve what we happen to believe so far. If we all work on self-improvement, we may converge on similar views; our networks will increasingly resemble each other. Indeed, that convergence may have already happened to large regions of our moral thinking. But the point is not agreement, it is the improvement of the network with which each of us begins.

By the way, improvement does not necessarily mean tidying up or removing inconsistencies, for a complex and rich network may be better than a beautifully organized one that misses the complexities and tensions of actual life. What shape a network should take is a major question for this book.

Given these premises, I propose that you actually diagram your moral beliefs as a network and then refine and reshape the diagram in response to questions that I suggest. I first explain how to generate a network and then offer eight exercises for improving it, each requiring a chapter to explain and justify.

If you are primarily concerned about methodology–about the general, philosophical question of how people do or should think morally–then it will be sufficient to spend a few minutes diagramming your own moral network to get a feel for the method I propose. You can then turn to my justification of the method in the pages that follow and consider the “meta-ethical” issues that arise. But I am at least as interested in a different audience, one that includes people who may never have heard the phrase “meta-ethics” and who don’t find methodological disputes in philosophy especially intriguing. They want to understand and improve their own moral views so that they can live better. That process will inevitably take more than one quick experiment with mapping. The initial analysis of your moral ideas is a start; but you must then contemplate, revisit, and revise the map over time for it to have any value. This is the aspect of the method that involves practice and self-discipline as well as abstract argumentation.

The map is a model, not the reality; it is a tool, and not the only one worth using. Making and revising the moral network map is therefore not the only activity you should use for moral reflection and self-discipline. An example of another valuable method, not emphasized here, is to construct autobiographical narratives that make meaning of one’s life so far. A narrative is quite a different model from a network. Still, I claim that moral network analysis is a valuable tool and also one that illuminates certain general truths about moral thinking that we should take into account even when we use different tools and methods.

Like Epicurus’ practice of reflecting on death, moral network mapping can be done both alone and with others. It will not immediately generate a new worldview, nor do I offer an argument for a whole network that you should adopt instead of your current one. (That would be the mode of systematic philosophy.) Rather, you can gradually improve your own structure of ideas by reflecting on the pieces and the overall shape in a continuous, disciplined way and sharing the results with friends. The result should be a richer, more thoughtful, more defensible structure of moral ideas that will more seriously influence your emotions, your habits, and your actions.

assessing a discussion

We discuss in order to address public problems together. We also develop morally through discussion–which, by the way, I would define very broadly to encompass a conversation with your neighbor over the backyard fence, with Leopold Bloom in the pages of Ulysses, with Angela Merkel through the New York Times, with Jesus in prayer, or with your late parent through memories and imagination.

I posit that the quality of discussion is a function of the skills, attitudes, and beliefs of the participants; the nature of the question under consideration; and the format. An individual’s contribution to a good discussion must be understood in context, because a given discursive act (such as making a concession or repeating a claim) can either be helpful or harmful, depending on the situation.

The tool I would use to assess discussion is a network map, where the nodes are the assertions made by the participants, and the links are explicitly asserted connections, such as “P implies Q” or “P is an example of Q” or “P is just like Q.” The network grows as the conversation proceeds–except when people stop adding new ideas and links–and each contribution can be assessed in terms of how it changes the network. A person’s statement can (for example) make a network larger, richer, denser, or more coherent.

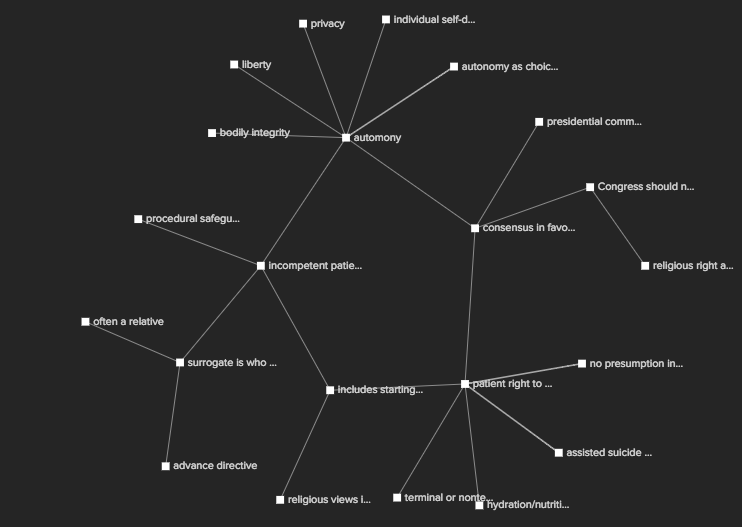

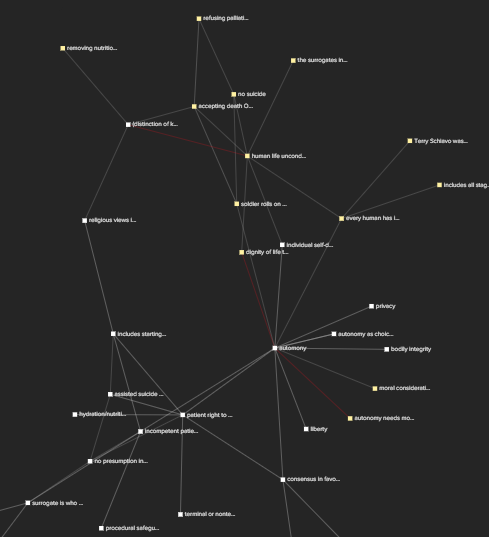

As an illustration, I’ve mapped a 2005 Pew Research Center debate on the right to die (prompted by the then-recent Terry Schiavo case) that involved Daniel W. Brock (a medical ethicist), R. Alta Charo (a law professor), Robert P. George (a political theoriss), and Carlos Gómez (a hospice physician). The transcript is here and my map can be explored here:

This topic (end-of-life decisions) has certain features: it raises fundamental metaphysical questions rather than empirical questions that could be settled with data. It poses absolute and irrevocable decisions, unlike questions about the distribution of scare resources, which can be negotiated. As for the format, it involved relatively long prepared statements by just four experts, in contrast to a free-for-all among a larger group, which would have a different structure. And the speakers, although diverse in perspectives, were all accustomed to a certain style of argument (relatively abstract and organized). It would be interesting to contrast this transcript to, for instance, a New England town meeting about a budget.

Dan Brock goes first and has a chance to lay out a position in favor of allowing a patient or her surrogate to end life support. His position is neatly organized, with the principle of autonomy at the center. He names that principle as the underlying rationale for a series of professional reports and court decisions that represent what he calls the current consensus. He connects autonomy to several related concepts: bodily integrity, privacy, self-determination, and choice. He draws the explicit implication that an autonomous patient must be able to choose or refuse any treatment. He adds the idea that when a person is incapable of exercising autonomy and has not made an advance directive, the best course is to empower a surrogate to choose. And he denies that the patient’s or surrogate’s choice should be constrained by supposed distinctions between starting versus stopping care, hydration/nutrition versus medical treatment, or a terminal versus a stable condition. Below is his position, isolated from the rest of the network.

Brock’s position is consistent (no nodes contradict each other), coherent (all nodes are connected), and centralized around the concept of autonomy. I would attribute those features of his position to: 1) the format (he gives prepared remarks that come first in a debate), 2) the professional style of the speaker (a professional philosopher), 3) the nature of the topic (bioethics), and 4) Brock’s position as a liberal who strongly favors autonomy. Indeed, Robert P George, the conservative theorist, says later in the debate: “liberals have to come up with a justification for placing autonomy in the central position in the first place, and that requires the defense of a moral proposition.” Note George’s use of a network metaphor to characterize Brock’s view.

Dr. Carlos Gomez speaks second. Unlike Dan Brock, he doesn’t produce a single, organized argument with explicit connections than link all of his ideas. I count nine different clusters of points in his remarks. Gomez’ points–isolated from the rest of the network–are shown below.

An important claim for Gomez only becomes evident to me (although this might be my own limitation as an interpreter) during the following exchange from the Q&A:

MODERATOR: Actually, before we go to the next question, when you said autonomy misses something essential in this sort of doctor-patient relationship, would you elaborate a little bit more on what that means in the real world?

MR. GOMEZ: Yeah, I’ve never had a patient knock on my office door, come in, sit down, and say, “I’m here to exercise my autonomy.” Now I may be a little too glib there, but what I’m suggesting is that one of the reasons that they are coming to me is precisely by nature of what I profess as a physician, by nature of what I know in terms of my skills, and also by nature – and on this I think Robby is dead on – by nature of the fact that there is a moral construct to what it means to be a physician or a nurse, or any other professionals that professes publicly what they’re going to do.

I think what Carlos Gomez has been implying all along is that nurses and doctors are required to show care for a patient, and an ethic of care is inconsistent with ending the patient’s life. Further, caregivers should have a strong voice in the debate about bioethics. Unlike Dan Brock, however, Gomez does not present that position as an organized argument but alludes to it with relatively scattered claims about how, for instance, there is actually no consensus about end-of-life treatment and the press is uninformed about hospice care. If I were to evaluate Gomez’ participation, I would say that he is less rhetorically effective than he might have been because he never states a claim that actually is central for him. The moderator assists not only Gomez but also the group by drawing out one central node that had not been clear before. On the other hand, Gomez clearly contributes ideas to the conversation and connects many of them to points already introduced by Dan Brock; so he broadens and enriches the discussion.

Alta Charo, a law professor, speaks third. She makes a cluster of points about how people mistake biological patterns for moral imperatives, and a related cluster of points about how sometimes the law appropriately creates “fictions” that are not based on biology, such as the idea of adoptive parenthood. She also makes at least nine other points that don’t explicitly connect to these two clusters. Her view is about as coherent as Carlos Gomez’. However, she is in a different position from him. She generally holds the same liberal position as Dan Brock, who has already spoken. It would not contribute to the conversation for her to repeat Brock’s argument for the centrality of autonomy, although she does state that choices about life must be personal and free. Instead, she builds ideas around the structure than Dan Brock has already laid out.

George follows Charo, and he lays out an alternative view to Brock’s, in which autonomy is explicitly not the central idea. Instead, “human life, even in developing or severely mentally disabled conditions, [is] inherently and unconditionally valuable.” His structure is about as consistent, coherent, and centralized as Brock’s, but it has a different center. Below is shown a network consisting only of the ideas proposed by Brock and George. “Human life is unconditionally valuable” is a central node in the top third of the picture; autonomy is a different center about two-thirds down.

The two networks touch at multiple points, either because George contradicts Brock (I show explicit disagreements with darker lines) or because he acknowledges specific areas of agreement.

Later, in the Q&A, George makes a discursive move that can sometimes be helpful to a group. He says, “As much as I love disagreement and dissent, I think that on one point on which Carlos and Dan thought they were arguing, there’s not actually a disagreement.” This is an example of tying together two points that have already been made in order to increase the coherence of the network. It is a helpful move–unless the two points are not actually alike.

By the time the session ends, the whole network is fairly connected. But certainly, no agreement has been reached, and two nodes remain central for different people but mutually inconsistent. That may be an inevitable feature of debates about the ends of life, or it may be a function of the way these speakers reason about such questions. Although they are speaking lightly at this juncture, Brock and Gomez imply a serious point about the impasse between them:

Dan Brock: Well Carlos and I first met on a PBS show about assisted suicide I guess 15 years ago, was it, Carlos? And we disagreed then roughly the way we do now, so –

MR. GOMEZ: I’m unteachable.

MR. BROCK: So am I.

I would hope that more mutual learning can occur when issues are either more empirical or more negotiable than this one is.

The post assessing a discussion appeared first on Peter Levine.

it’s not just what you think, but how your thoughts are organized

We come into the world with no moral ideas at all and must learn them from others. We learn not just from arguments and explicit principles, but also by observing practices and experiencing emotional reactions.1 We must make judgments about complex, evolved, historically contingent phenomena (such as, among many others, marriage, democracy, and art) that we cannot apprehend as wholes but must learn to assess from accumulated and vicarious human experience.2 In Habermas’ terms, we begin with a “Lifeworld” formed of our shared experiences and improve it through explicit deliberation with diverse people in civil society.3

Some people are much better at this process than others are, and we can explain why by understanding their moral worldviews as networks of ideas and connections and considering how their whole networks are organized. Consider these hypothetical discussion partners:

- Aaron constantly returns from any situation or moral consideration to the same value. He considers that value immediately relevant to all others and nonnegotiable. It defines his moral identity and appears to him manifestly true. Deliberating with Aaron is impossible, but not because his network contains a foundational belief in the sense of one that is “infallible, or indubitable, or incorrigible, or certain.”4 What makes him a poor deliberator is rather the over-centralization of his network of moral ideas. One cannot find a route around his core principle.

- Bao endorses a lot of moral ideas, examples, and principles. But he cannot connect one to another. Asked why he believes P or Q, he has nothing to say about his reasons, let alone can he offer a chain of reasons that connects P to Q. It is hard to talk to Bao because his network is disconnected.

- Carlos simply has nothing to say about many choices, dilemmas, and cases that arise in conversation and practice. He can discuss some topics cogently, but many others seem not to interest or concern them. The problem with Carlos’ network is that it is too small (having too few nodes) or has too restricted a scope.

- Dominique cheerfully holds both P and not P, depending on her mood or perhaps her self-interest or convenience. Dominique frustrates deliberation because her network harbors blatant inconsistencies that she does not attempt to resolve.

- Eduardo is committed to one idea, like personal liberty or economic equality, and he will not recognize the legitimate pull of other values that conflict with his summum bonum, e.g., order and security, solidarity and community, or democracy. Eduardo’s network is consistent but impossible to connect to if one holds other values.

- Fiona holds many ideas and can thoughtfully connect them to each other. But asked whether she has tried to apply any of his ideas in practice or observed them in application, she demurs. Fiona’s network is well structured for talk but disconnected from experience.

This list can be extended. The point is that the structure of a moral network is important. That follows from the premise that we each begin with whatever ideas and connections we happen to hold, and our responsibility is to refine the whole set in discussion and collaboration with others. In that case, we should be concerned not only about the various values that we endorse, but also with how they are configured. The best networks for discussion are likely rich, complex, connected, not overly centralized, and not necessarily fully consistent.

Notes

- Cf. Owen Flanagan, “Ethics Naturalized: Ethics as Human Ecology,” in Larry May, Andy Clark , and Marilyn Friedman (eds.) Mind and Morals: Essays on Ethics and Cognitive Science (Cambridge, MA: MIT, 1998) p. 30: “The community itself is a network providing constant feedback to the human agent.”

- See Richard N. Boyd, “How to be a Moral Realist,” in Geoffrey Saye-McCord, Essays on Moral Realism (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1988), p. 205: ““Much [moral] knowledge is genuinely experimental knowledge and the relevant experiments are (“naturally” occurring) political and social experiments whose occurrence and whose interpretation depends both on “external” factors and upon the current state of our moral understanding.” Cf. Friedrich A. Hayek, The Constitution of Liberty (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1960), pp. 59-65

- Habermas’ preferred metaphor is a horizon, but he explicitly mentions networks in Jürgen Habermas, Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy, trans. by William Rehg (Cambridge: MIT Press, 1996), p. 18.

- Geoffrey Sayre-McCord, “Coherentist Epistemology and Moral Theory,” in Saye-McCord, p. 154.

The post it’s not just what you think, but how your thoughts are organized appeared first on Peter Levine.

how judgment is structured

Everything is judged

As you walk through the supermarket, your senses absorb data from tens of thousands of objects. Each presents a binary choice: buy or don’t buy. That is a value judgment, even if the only value consideration is whether you happen to like the item’s taste. But most likely, other considerations are relevant as well. Is it healthy? Would your toddler eat it? Is it worth the price, the weight in your basket, and the space on your shelf? And perhaps: were animals harmed in making it? Were people exploited? How much carbon was used to make it? Does the picture on the box objectify the human subject?

You can widen the lens, too, and ask not about individual items on the supermarket shelves but about the supermarket as a whole: Should you be spending your time there? Should your money flow to its owners? Should our systems of production and exchange be organized this way? Who cannot shop here?

And the choices are not really binary: buy or don’t buy. For each object, you could also appreciate it, recommend it, make a note to buy it another time, disparage it, steal it, throw it out the window. You could even act like Allen Ginsberg in “A Supermarket in California” (1955):

I saw you, Walt Whitman, childless, lonely old grubber, poking among the meat in the refrigerator and eyeing the grocery boys.

I hear you asking questions of each: Who killed the pork chops? What price bananas? Are you my angel?

I wondered in and out of the brilliant stacks of cans following you, and followed in my imagination by the store detective.

We strode down the open corridors together in our solitary fancy tasting artichokes, possessing every frozen delicacy, and never passing the cashier.

These lines remind us that we experience more than goods in a store. There are also the other shoppers and workers, real and imagined, alive and dead, with their words and desires. We can walk past anyone or anything without making a judgment; but that, too, is a choice and it implies a judgment.

Everything is structured

It is a familiar observation that experience presents us with too much data, and it all flows together without clear separations in space or time. William James, The Principles of Psychology, 13:

The law is that all things fuse that can fuse, and nothing separates except what must. … The baby, assailed by eyes, ears, nose, skin, and entrails at once, feels it all as one great blooming, buzzing confusion; and to the very end of life, our location of all things in one space is due to the fact that the original extents or bignesses of all the sensations which came to our notice at once, coalesced together into one and the same space.

Therefore, we organize, categorize, simplify, select. We don’t consider each box of Kellogg’s Cornflakes but the whole product line, or perhaps breakfast cereals taken as a class.

Aristotle began the discussion of categories with his book of that name, in which he argued that any thing could be classified in ten ways: where it is, when it is, its relation to other objects, its action, its being acted on, etc. In Kant’s version, the categories were not features of nature but tools of reason—by which he meant not merely human reason, for any animal, angel, or alien would have to use the same tools if it reasoned. Parting with Aristotle and with Kant, we could instead attribute these categories to human psychology (treating them as phenomena of our evolved, physical brains) or of language, which has a deep structure shared by all human beings.

But what matters most to moral judgment in a supermarket are not these fundamentals of location, duration, action, etc., but a more evident type of classification. Objects in a store are for sale or not, expensive or not, healthy or not. Such categories are not features of nature, reason, psychology, or the deep structure of language. They are constructed. Objects in a store have been designed and labeled so that they fit in various categories, for reasons determined by their owners and influenced by governments. Even the people wear various kinds of labels that intentionally classify them. The building as a whole also has marked boundaries and a location on an organized street plan. Although these categories have been constructed, no one controls them completely, for nature intrudes (an object isn’t healthy just because someone says it is) and because each observer has some individuality. I may think a given product is desirable even if you do not.

Some of these categorizations are morally neutral or unexceptional. Some are helpful. But some may be unethical or even evil: for instance, if they encourage us to buy products that gradually kill us or that have required murder and expropriation to create. The typical object is not actually lethal but it does have bad as well as good features. The same is true of each socially constructed category of objects, such as all the breakfast cereals or all the vegan items. And it is true of each institution that has constructed and maintained these categories.

But how can we tell how to judge right? From early school days, we are taught to distinguish between facts, which can be demonstrated or disproved, and opinions, which belong to the person who holds them. Moral judgments seem more like opinions than facts, hence not demonstrable or disprovable. Some people also argue that science is the only path to truth, and science has nothing to say about which objects are good or bad. There is not one “scientific method,” but many methods that scientists use: observation, measurement, classification, model-building, experimentation. But all scientific methods involve rigorous efforts to insulate the facts—to the greatest degree possible—from the observer’s value-judgments.

Such efforts are necessary because we have affective reactions to objects—positive or negative emotional surges that come faster than articulate thought. Francis Bacon already observed that “human understanding when it has once adopted an opinion (either as being the received opinion or as being agreeable to itself) draws all things else to support and agree with it.” Recent psychology insists that our emotional surges–what we find agreeable or disagreeable–explain the thoughts that follow them. We have a feeling and then we rationalize it with conscious ideas.

Thus we need not worry that we are morally apathetic, but we should worry that we are morally wrong. Consider, for example, the experimental evidence that most White Americans (and not a few African Americans) have immediate negative responses to Black faces. That is an example of a strong affective response that is relevant to such everyday experiences as shopping in a supermarket, where both the real people and some of the images on the goods appear to modern Americans to have racial identities. If, after science sifts out the facts, we are left only with instinctive reactions–including some invidious ones–which we then justify with moralizing rationalizations, we are in deep trouble.

Judgment, too, is structured

Individual moral claims are indeed untrustworthy, whether they are instinctive and inarticulate affective reactions or carefully constructed moral propositions. Taken one at a time, they do appear to be nothing more than opinions. We know that people’s opinions differ, and so we have grounds to be skeptical that any are better than others.

But moral claims do not come alone. We connect each one to others. I favor marriage equality–why? Because gay marriage is like heterosexual marriage. Because people want to love and be loved exclusively and durably. Because marriage tends to benefit the children. These are connections among pairs of ideas. They start to form a network. The network is much more persuasive than any particular idea.

First, the network bridges facts and values. Many of the claims in the previous paragraph are empirical, or partly so. Yet the same sentences that make empirical claims also embed deeply moral concepts.

Second, the network has formal features that cannot be attributed to individual ideas. For example, it is more or less consistent and coherent. Those are the most frequently cited criteria of good moral thought, and I believe they are overrated. (Evil fanatics are often highly consistent.) But we can add other formal criteria: networks of ideas ought to be rich, complex, and dense.

Third, a network permits interaction with other people. If I believe X and you do not, there is not much to discuss. But if I believe X because of Y, and Y because of Z, and Z because it resembles A, there is probably some node or connection in what I’ve said that you can lock onto.

My own structured network of ideas reflects the influences on me so far. If I had been born a gentile German ca. 1900, I probably would have favored Hitler in 1939 (if I had lived that long). Because I was born to an American Jewish father in 1967, it was easy for me to see that Nazism was evil. Still, I was correct in that judgment. The quality of the moral network with which we begin to reason is a matter of luck (“moral luck“). It is up to us, however, whether we test our structured ideas with people differently situated and motivated and revise it accordingly.

The post how judgment is structured appeared first on Peter Levine.