Summarizing a body of empirical research, the Duke psychologist Nina Strohminger argues that what constitutes our identity is our moral character, not (for instance) the memories that we have stored so far. Asked what characteristics a soul would hypothetically carry into another body, subjects choose the soul’s moral character. Asked which psychological changes would make someone into a new person, subjects select moral changes above total amnesia or an inability to recognize moral features. Given a chance to improve their own moral character with an imaginary pill, people say they would decline because that would mean abandoning their selves.

According to Strohminger, “moral features” constitute “the most important type of information we can have about another person.” She continues:

So we’ve been thinking about the problem precisely backwards. It’s not that identity is centred around morality. It’s that morality necessitates the concept of identity, breathes life into it, provides its raison d’être. … What is it to know oneself? … When we dig deep, beneath our memory traces and career ambitions and favourite authors and small talk, we find a constellation of moral capacities. This is what we should cultivate and burnish, if we want people to know who we really are.

I would like to connect this discussion to psychological research on how we perceive the identities of ordinary objects, such as apples and chairs. (This link may have been made already; I have not looked.) According to experiments by Sloman, Love, and Ahn, people perceive as integral or essential those features of an object that could not change without affecting many other features. Therefore, a network model is useful. Think, for instance, of the many features of an apple (its crunchy texture, sweet taste, origins on a tree, function of protecting seeds, color, size, role in Greek myths, etc). These features can be seen as nodes in a conceptual network. The nodes that we see as more definitive of appleness are the ones that have higher network centrality.

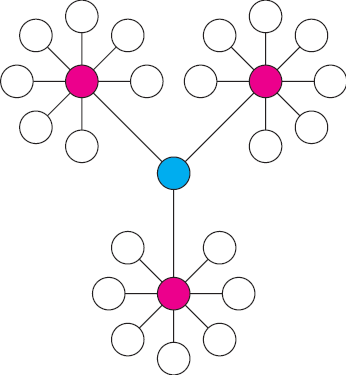

Likewise, I would model any person as holding many ideas in his or her head at any time. The individual ideas are all subject to change. Some are linked to others, forming a large, complex, and evolving conceptual network. Some of the nodes are moral ideas, however you define morality. When we think of another person’s identity, we should not cite just one or a few clear-cut principles or virtues. That would reduce the complex person to an abstraction. But we should have in mind a cluster of connected–although not always mutually consistent–nodes that are relatively central to that person’s whole network. These nodes cannot change without setting off a cascade of other changes that may be sufficient to alter the person’s whole character.

In short, as Strohminger writes, “the self is moral”–and I would add that the moral self is a network of ideas defined by the cluster(s) of relatively central nodes. That is what our souls would take with us into new bodies or a new life.

The post “the self is moral” appeared first on Peter Levine.