Here are three distinct goals that you might pursue if you see education as a means to improve a society. All three are plausible, but they can conflict, and I think we should sort out where we stand on them.

- Improving lives. What constitutes a better life is contested, as is the question of how a population’s welfare should be aggregated to produce a score for a whole society. The Human Development Index includes such components as mean life expectancy at birth and “mean of years of schooling for adults.” You might think that what counts is not these averages but the minima: how much life, education, safety, health (etc.) does the worst-off stratum get? Their circumstances can improve with balanced and humane economic development. Arguably, the worst-off 20 percent of Americans are better off than Queen Elizabeth I was in 1600, because you’d rather have clean running water in your house than any number of smelly and disease-carrying servants. But our minimum is still not very good, since some Americans sleep on grates or are warehoused in pretrial detention facilities because they can’t afford bail.

- Equity. By this I just mean the difference between the top and the bottom, e.g., the GINI coefficient, although one might consider more factors besides income. Algeria and Sweden have almost identical levels of equity (GINI coefficients of 27.2 and 27.6, respectively), but Sweden is much wealthier, with 3.3 times as much GNP per capita as Algeria has.

- Mobility. This means the chance that someone born at a relatively low level in the socioeconomic distribution will rise to a relatively high level. By definition, that means that someone else must fall. (Or one person could fall halfway as far, and a second person could fall the other half way, to make room for the person who rises all the way up.) By definition, mobility is zero-sum, being measured as the odds of moving up or down percentile ranks. If everyone moves up, that’s #1 (an increase in aggregate welfare), not a sign of mobility.

These three goals can come apart. For example, equity coincides with very poor human development when everyone is starving together. Sweden has high human development and high equity but not much mobility: Swedish families who had noble surnames in the 17th century still predominate among the top income percentiles. It’s just that it doesn’t matter as much that you’re at the bottom in Sweden, because the least off do OK there.

To be sure, the best-off countries in the world tend to be more equitable and prosperous, and there’s a long list of very poor countries that are also highly unequal and (I guess) have little mobility. That pattern could suggest that the path to higher development requires equity. But that’s a contingent, empirical hypothesis, unlikely to be true across the board, and the goals are not the same.

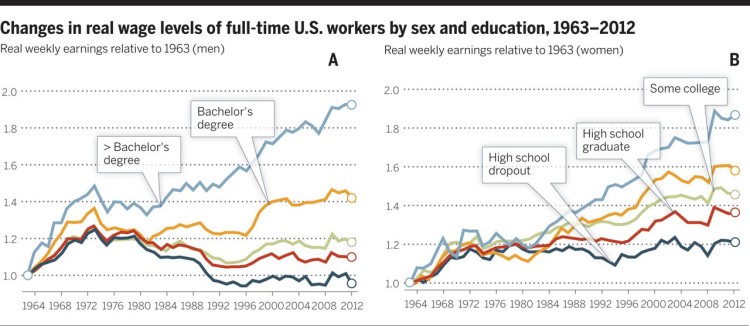

For proponents and analysts of education, the difference matters. Presume that you are concerned with improving human lives. One way to do that is to expand the availability of education. More people reach higher levels of education today than did in 1930–and more people lead safer, longer, lives. This strategy won’t produce equity, however. As educational attainment has risen in the United States, the most educated people have increased the wage gap.

Another way to enhance human welfare is to yield outputs that benefit everyone: skillful doctors and engineers who have great new technologies, medicines, training, etc. To get the best results, it might be smart to concentrate resources at very high-status institutions. The universities that produce the most scientific advances tend to be highly competitive institutions in inequitable systems like the US.

Presume that you want to promote mobility. Then you must reduce the correlation between parents’ and children’s educational attainment. That means admitting and advancing more students whose parents were disadvantaged. It also means, by definition, admitting fewer students from advantaged homes. Increasing the number of total slots is an inefficient way to enhance mobility. Mobility requires competitiveness: when people can compete better, newcomers can more easily knock off incumbents. When individuals are protected against failure, mobility is hampered.

Mobility also operates at the level of communities. In a system of Schumpeterian “creative destruction,” Detroit can fall while Phoenix rises. European countries intervene much more effectively than we do to protect their deindustrializing cities. That is better for human flourishing, but it may also hamper mobility.

Finally, presume that you really want to improve equity. One way to do that would be to improve the education of the least advantaged while holding the top constant. Another way would be to lower the quality and value of the education received by the top tier. Very few people would support doing that, even if it improved equity. That’s because most people think that welfare and mobility are at least as important as equity. (I leave aside liberty, although that is also a valid and important principle.)

Hybrid goals are possible. Perhaps what we want is to maximize the welfare of the least advantaged while not allowing inequality to get out of hand or mobility to vanish. That’s arguably the outcome in Denmark and Sweden. The US may under-perform regardless of how you weigh the three goals. We have vast inequality, limited mobility, and not much safety or health for a large swath of our people. But even if we can make progress on all three fronts at once, they are still different directions.

See also: to what extent can colleges promote upward mobility?, when social advantage persists for millennia, and the Nordic model

on-Cogs’ and ‘Soft Skills.'”

on-Cogs’ and ‘Soft Skills.'”