(Oxford, OH) By the 1980s, a large literature distinguished the “New Social Movements” from older strands of politics. Jürgen Habermas chose to list the following New Social Movements then active in Germany: “the anti-nuclear and environmental movements,” “the peace movement”; “the citizens’ action movement”; the “alternative” movement that included urban squatters and new rural communities; movements of “minorities (the elderly, homosexuals, disabled people, etc)”; support groups and youth sects; “religious fundamentalism”; the “tax protest movement”; “school protests” by parent associations; “resistance to modernist reforms”; and “the women’s movement” (1981, p. 34).

Some of these might be classified with the left, and others (notably, tax protests and religious fundamentalism), with the right. In retrospect, it is debatable whether they formed a meaningful category or could be distinguished sharply from the “Old” social movements, such as labor unionism and civil rights in the USA.

My view is that these movements did represent a new stage of politics in the wealthy democracies. That stage has passed, however, as new problems have come to the fore and as the social movements of ca. 1968-1985 have become institutionalized in the nonprofit sector, thus losing their emancipatory role. These changes mean that it’s important to compare our time with the 1970s and early 1980s and to envision productive combinations of the Old and New Social Movement forms.

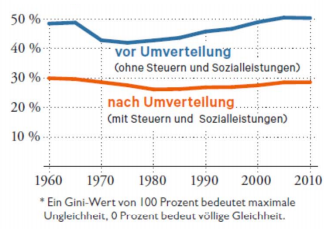

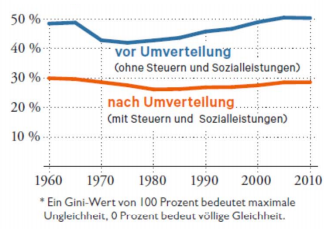

One way to summarize the story is that zero-sum struggles over scarce goods and basic rights (civil, political, and economic) were essential to politics up until the 1960s. However, changes in the political economy of the richest nations and the most advanced US states had moved those struggles into the background by ca. 1970. Strong economic growth made possible the elimination of absolute poverty in countries like the Federal Republic of Germany. Thanks to labor’s unusually high share of income, the power of unions and parties, and the disruptions of World War II, working people exercised considerable political power through the state. That meant that even as pre-tax incomes became unusually equal, incomes after taxes and welfare payments grew even more equal. Also, thanks to constitutional reforms, most citizens could count on fairly equal legal rights.

“Income Inequality in Germany Measured by the GINI-Coefficient” (Top line is before redistribution; bottom line is after. Zero would be complete equality.)

At the time, many American liberals and European social democrats felt that the success of the democratic welfare state should simply be consolidated. The emerging neoliberal movement of Thatcher and Reagan argued that the welfare state was inefficient and illiberal and needed to be rolled back; their ideas gained momentum with the stagflation of the 1970s. But thinkers like Habermas, Offe, Mansbridge, Beck and (in a different vein) Foucault adopted more positive views of the New Social Movements.

Writing in 1985, Offe observed that European capital and labor had reached a postwar agreement.Unionized, private-sector employment would deliver prosperity, and workers would be free to develop identities, interests, and memberships during their youth and student years, their growing leisure time, and their lengthy retirements. The issues for politics were growth, economic distribution and security. These were contested within narrow constraints (for instance, everyone was a Keynesian) and not expected to occupy much public attention.

The New Social Movements then arose when people critically assessed the patterns that prevailed in the domains that were supposed to be left private, such as childhood, marriage, church, and nature. Activists demanded large-scale change in these domains, but not via direct state action, because they opposed “manipulation, control, dependence, bureaucratization, regulation, etc.” (Offe, 1985, p. 829).

Offe argued that “middle-class radicals” played a disproportionate role in these New Movements. Traditionally, workers and the poor had struggled against bourgeois notions of propriety and normality. However, the organized post-War working class had traded cultural conventionality for prosperity, leaving affluent students, public sector workers, and professionals to demand room for “alternative” ways of life (pp. 823-5).

Habermas drew a distinction between System and Lifeworld. A System is governed by instrumental rationality: it treats individuals as means to a given end. Both state bureaucracies and capitalist markets are Systems. As a democratic socialist, Habermas favored a relatively large state bureaucracy controlled by a popularly elected legislature. But both governmental and market Systems were problematic when they extended into the Lifeworld composed of authentic human relationships. Thus, even as a welfare state like the Federal Republic of Germany neared success at the “old” goals of eliminating poverty and narrowing gaps of wealth and power, it risked colonizing the Lifeworld by turning everyone into a consumer and an employee, employer, or welfare client and then regulating their behavior accordingly. Habermas wrote in 1981:

Precisely these roles are the target of protest. Alternative praxis is opposed to the profit-oriented instrumentalization of professional labor, the market-dependent mobilization of labor, the extension of competitiveness and performance pressure into elementary school. It is also directed against the process whereby services, relations and time become monetary values, against the consumerist redefinition of private life spheres and personal life styles. Furthermore, the clients’ relation to public service agencies is intended to be broken and restructured according to the participatory model of self-help organizations (p. 36).

He proposed, “at least cursorily,” that all the New Social Movements represented “resistance to tendencies to colonize the lifeworld (p. 35). That was true, he thought, of the conservative movements as well as the radical ones. To apply his thinking to the US context, we might say: Whether you moved to Vermont to go back to nature or to New Hampshire to live free or die, you were opting out of systems seen as instrumental. Habermas concluded that even if the New Social Movements were “unrealistic,” they offered symbols of resistance to the “colonization of the life-world” (p. 37).

For both Habermas and Offe, the New Social Movements were different from the Old because they no longer addressed issues that could be resolved with money or rights. Instead, these movements asked “how to defend or reinstate endangered life styles, or how to put reformed life styles into practice” (Habermas, p. 33).

One could debate whether feminism and gay liberation were really “life style” movements as opposed to struggles for basic equality (thus continuous with the “Old” social movements), but they certainly highlighted informal, interpersonal, and attitudinal issues more than older movements had. Habermas observed that “High value is placed on the particular, the provincial, small social spaces, decentralized forms of interaction and de-specialized activities, simple interaction and non-differentiated public spheres. This is all intended to promote the revitalization of buried possibilities for expression and communication. Resistance to reformist intervention also belongs here” (p. 36).

Similarly, Jenny Mansbridge observed that during the ferment of the late 1960s and 1970s, small groups “appeared everywhere like fragile bubbles.” These groups shared certain features. Decisions were made in face-to-face meetings, after much discussion, when someone expressed the consensus of the group. There were no formal distinctions among participants or offices. And there was a strong norm against making self-interested statements. Face-to-face, consensual democracy was meant as an alternative to what Mansbridge called “adversary democracy,” which presumes that interests conflict and that decisions must always have winners and losers (Mansbridge, 1983).

Foucault, meanwhile, regarded the welfare state as a particularly efficient and all-encompassing instrument of “discipline.” Not only was he supportive of the New Social Movements, but this great radical “was highly attracted to economic liberalism: he saw in it the possibility of a form of governmentality that was much less normative and authoritarian than the socialist and communist left, which he saw as totally obsolete. He especially saw in neoliberalism a ‘much less bureaucratic’ and ‘much less disciplinarian’ form of politics than that offered by the postwar welfare state. He seemed to imagine a neoliberalism that wouldn’t project its anthropological models on the individual, that would offer individuals greater autonomy vis-à-vis the state” (Zamora, 2014).

Ulrich Beck, evidently drawing on Habermas, offered the perspective that the core social problem had shifted from the distribution of wealth and power to the distribution of risk. Human beings had always faced risks, but new dangers (e.g., nuclear power plants melting down, chemicals in one’s food) were harder to diagnose and prevent, less a matter of individuals’ negligence than outputs of Habermasian Systems, and not necessarily correlated with wealth. “Risk positions are not class positions,” he wrote, because people with money may sometimes face more risk, and risk can spread contagiously (Beck 1986; English translation 1992, pp. 39, 44). This is one reason that Offe’s middle-class radicals were so prominent in the New Social Movements, all of which were “environmentalist” in the broadest sense of that term.

It is important to note that in the other half of Europe, movements were also struggling against a System–in their case, the single-headed System of state communism. Like the Western New Social Movements, they built up alternative spaces meant to be authentic (“Living in Truth”) and voluntary. “The mainstream of the [Polish] opposition was deliberately and profoundly anti-political,” writes Aleksander Smolar. “Faced with the strategic choice described by Adam Michnik in his letter from prison, the answer of the opposition was clear. The objective was not to defeat the ruling power but to progressively liberate society from its control” (Smolar, 2009) by building a better alternative in civil society.

Four decades later, the basic achievements of the welfare state seem fragile, its objective of ending absolute poverty receding. That breathes some new life into the “Old” social movements’ objective or demanding redistribution from the state. In that light, Occupy Wall Street represents an interesting development. Its modes of interaction come straight from the New Social Movements. So does its refusal to make highly concrete demands on institutions. Offe wrote, “Movements are incapable of negotiating because they do not have anything to offer in return for any concessions made to their demands. … Movements are also unwilling to negotiate because they often consider their central concern of such high and universal priority that no part of it can be meaningfully sacrificed” (Offe, pp. 830-1). I think there was some of that spirit in Occupy. On the other hand, Occupy’s evocation of “The 99%” made it universalistic in a way reminiscent of the Old Left instead of the New Social Movements, and it returned to questions of economic redistribution. It pursued an Old Left agenda in New Social Movement form–not successfully as such, but perhaps subject to improvement.

Meanwhile, the norms that distinguished the “New” social movements have found lasting and quasi-secure places within institutions, particularly in nonprofits and universities. Many people who work full-time for service-learning centers, community development corporations, youth programs, and other NGOs combat explicit and implicit biases, prize authentic local communities and traditions, emphasize dialog and deliberation, work in (or emulate) voluntary associations, try to create zones of consensus and relational ethics, and stay clear of both state bureaucracies and corporations. Many a young graduate of these programs wants to start an urban agriculture nonprofit or develop curricular materials, but would never think of working for the government or running for office.

I’ve previously described these programs as the home of the most authentically conservative politics in the US today, if “conservative” means localism, sustainability, deference to indigenous traditions, humility and skepticism about expertise, and a resistance to state power.

One view is that the New Social Movements were conservative (in this sense) from the start, and that was always bad news. The left, wrote Todd Gitlin in 1993, is the tradition of explicitly universalistic values, whether those are liberal, Marxist, or Christian-inflected (e.g., in the Civil Rights Movement). “Universal human emancipation,” he argued, is the core of all authentically revolutionary and reformist politics. Its enemy is the kind of conservatism embodied in the New Social Movements and in many of today’s NGOs. Yes, progressive movements must address injustices related to sexuality, gender and color–not merely economics–but always in the explicit pursuit of a common good.

A related critique is that the New Social Movements have depicted “the oppressed [as] innocent selves defined by the wrongs done to them” and have demanded protection. Once former participants in New Social Movements take up roles inside institutions, they start to manage and administer fairness, understood as a set of rules and regulations that protect the disadvantaged (see Bickford 1997 for a useful summary of a position that she doesn’t hold). In contrast, real social movements emancipate.

In 1985, Offe judged that the New Social Movements held a “presently marginal, though highly visible power position.” The question was whether they would “transcend” that situation, which would require forming alliances. They could align with the traditional institutional left (socialist parties and unions), or with traditionalist conservative movements. Or the traditional conservatives and the institutional left might unite to marginalize the New Social Movements. Offe thought all three scenarios were possible

Right now, the nascent movement of resistance to Trump–and kindred developments in countries like Hungary–again look “marginal, though highly visible.” These movements are defending fundamental and universal rights in a way that was typical of the Old Social Movements. They draw on the New Social Movements for some of their modes of political engagement, but they are beginning to connect to political parties and campaigns. So far their rhetoric is mostly defensive, which was typical of the New Social Movements as a whole. Offe observed that the “positive aspects” of these movements were “mostly articulated in negative logical and grammatical forms, as indicated by key words such as ‘never,’ ‘ nowhere,’ ‘end,’ ‘stop,’ frieze,’ ‘ban.’ etc.” (Offe, p. 830).

We will see whether today’s incipient movements begin to develop more expansive positive agendas and shift from merely opposing Trump (and his like) to envisioning and demanding a substantially different political economy and a new social contract. That would also require alliances, I think, with what remains of the institutionalized left, including the Democratic Party.

See also: what is a social movement?; what activist movements will look like in the Trump era; questions for the social movement post Ferguson; Habermas and critical theory (a primer); and perspectives on identity politics.

References

- Beck, Ulrich. Risk society: Towards a New Modernity. Vol. 17. Sage, 1992.

- Bickford, Susan, “Anti-Anti-Identity Politics: Feminism, Democracy, and the Complexities of Citizenship,” Hypatia, vol. 12, no. 4 (1997).

- Gitlin, Todd, “The Left, Lost in the Politics of Identity,” Harper’s Magazine, 1993

- Habermas, Jürgen, “New Social Movements,” Telos, September 21, vol. 1981, no. 49 (1981) pp. 33-37

- Mansbridge, Jane J. Beyond Adversary Democracy. University of Chicago Press, 1983.

APA

- Offe, Claus, “New Social Movements: Challenging the Boundaries of Institutional Politics,” Social Research, vol. 52, no. 1 (Winter 1985), pp. 817-68.

- Smolar, Aleksander. “Toward ‘Self-Limiting Revolution’: Poland, 1970-1989.” in Adam Roberts and Timothy Garten Ash, eds., Civil Resistance and Power: The Experience of Non-Violent Action from Gandhi to the Present (New York: Oxford University Press, 2009)

- Zamora, Daniel, “Can we Criticize Foucault?” The Jacobin, December 2014.