(Amtrak between NYC and Boston) Here are opening remarks I gave today at a Ford Foundation convening on Educating for Democracy:

I have attended many meetings on civic education over the past 20 years. This one looks much more exciting than almost all of them, for two major reasons: the range of people who have come here today, and the seriousness of the main discussion topics.

Civic education is not a matter of consensus. It is not one uniform movement. It is—and it ought to be—a field of diversity and disagreement, just like our democracy itself.

Some in our field are concerned primarily with ensuring that young people understand the basic structure of the U.S. government as it is enshrined in the Constitution and its amendments. They argue that our republic deserves respect and support, and they fear that the system will weaken unless students are taught to understand and appreciate it. They tend to emphasize the founding era and the national level of government and want to foster an appreciative attitude toward the political system and a sense of unity about our history and principles.

Other advocates are concerned primarily with empowering young people to participate in civic life, with an emphasis on civic action, most of which takes place at the local level. From this “Action Civics” perspective, it may be worthwhile to gain some understanding of the U.S. Constitution (for instance, students should know that speech enjoys constitutional protection), but it may be just as important to investigate local social conditions or to know who exercises real power in the community. Besides, those who favor “Action Civics” tend to value a critical stance toward the existing political system, and they often call for instruction that emphasizes the value of diversity, localism, criticism, and action, not patriotism and unity and an understanding of core political documents and principles.

Those are just two philosophical orientations toward civic education. Many more exist.

People in this field also differ in the kinds of civic activity that we imagine as the successful outcomes of civic education. Are we looking for voting and participation on juries? Or social movements that challenge the justice system?

Are we hoping for voluntary service in communities? Following and discussing news produced by major professional news outlets? Or creating news and opinion?

Do we want to develop relatively small numbers of ethical and effective leaders in all communities, or get the average student to a higher level of civic knowledge?

Maybe most people in this room would say “All of the above,” but the list suggests a range of emphases and core concerns.

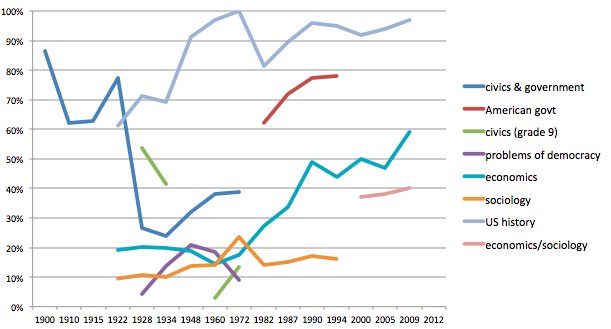

We also differ in where we see the most valuable forms of civic education occurring. Some would cite a mandatory civics class in middle school or high school. It reaches most kids in most states, lays an essential foundation of knowledge, and gives the students the benefits of trained and dedicated adult educators. Others would rather be almost anywhere except a 7th grade civics class. They may see the most important venues for civic education as grassroots community organizations, or church basements, or Twitter.

If you gave people involved in civic education the opportunity to ask all American kids to read just one item today, I’ll bet the nominations for that reading assignment would range from a pie chart of the federal budget to Elie Wiesel’s Night, from the “Mayflower Compact” to this hour’s Tweets with the “BlackLivesMatter” hashtag—and many, many more.

The purpose of today’s meeting is not to resolve these differences and reach consensus.

I’d actually like to repeat that: The purpose of today’s meeting is not to resolve these differences and reach consensus.

That will not happen with so many people and so little time. I don’t even think we want it to happen, because a robust effort to engage our young people in civic life must be diverse, heterogeneous, contested, and even competitive among different approaches and ideals.

We do hope that by bringing together a reasonably diverse range of perspectives and approaches we can help everyone understand that diversity. Each person here today should learn more about the points of agreement and disagreement and reflect on where you stand as individuals and organizations.

We are also hoping that you will leave today having seen new opportunities for your own involvement—opportunities to support the forms and venues and purposes that resonate most with you. We are hoping to display the powerful and exciting diversity of civic education.

Along the way, we also plan to explore three serious, difficult, challenging topics that confront everyone in the field. Each challenge will get a session to itself, but the day may do more to define and clarify the problems than to resolve them.

The first challenge is inequality. Our educational and political systems are profoundly unequal. They offer unequal opportunities to learn and to participate. How can we provide more equal civic education under those circumstances?

By the way, civics is not only a victim of deep social inequality but potentially part of the solution. We may be able to give youth the tools they need to run the country more equitably when they take it over, which they will in the 21st century. We also know that certain well-designed civic engagement programs help the individual kids who participate in them to flourish in our current society—to do better in school and life.

So inequality is the first topic. The second is polarization. The US political system is deeply polarized ideologically, and the American people are, too. That context makes civic education more difficult, because every classroom discussion, textbook adoption, or comment by a teacher is a potential flashpoint. Even the word “democracy” (as the name for what we are trying to teach) is now politically divisive in a way that was not true in the 1980s.

At the same time, civic education may contribute to addressing the challenges of polarization, if we can help young people learn to handle disagreement better than we older people do.

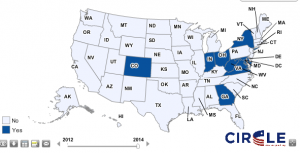

The final problem is scale. It is clear that many smallish programs work. They are great for the students who participate. It is also clear that our best classroom civics teachers have huge benefits for their own students. But it is much less clear how we can dramatically increase the scope and scale of such opportunities so that we reach all of our kids.

Some of the most obvious tools for increasing scale, such as tests and mandatory courses, are problematic. Either we already have these policies in place and they don’t seem to work, or they are politically untenable, or we have reason to doubt their potential. Yet we cannot be satisfied with excellent civic education as a sporadic, largely voluntary affair. We must take it to scale, even if no single strategy for accomplishing that will work on its own.

In my opinion, if we could make progress on inequality, polarization, and scale, we would move a long way forward. That would not only be a victory for civic education but for American democracy. I do not expect that everyone gathered here today will come to agree on one strategy for addressing these three challenging topics. That is not only unrealistic; it might actually be a little bit creepy. We should count it as a success if we have invited people here today who favor a range of strategies and disagree in part.

I can’t wait for the conversation to begin.

The post civic education in a time of inequality and polarization appeared first on Peter Levine.