[This is a cross-post from Sunlight Foundation's series OpenGov Conversations, an ongoing discourse featuring contributions from transparency and accountability researchers and practitioners around the world.]

As asserted by Jeremy Bentham nearly two centuries ago, “[I]n the same proportion as it is desirable for the governed to know the conduct of their governors, is it also important for the governors to know the real wishes of the governed.” Although Bentham’s historical call may come across as obvious to some, it highlights one of the major shortcomings of the current open government movement: while a strong focus is given to mechanisms to let the governed know the conduct of their governors (i.e. transparency), less attention is given to the means by which the governed can express their wishes (i.e. citizen engagement).

But striking a balance between transparency and participation is particularly important if transparency is conceived as a means for accountability. To clarify, let us consider the role transparency (and data) plays in a simplified accountability cycle. As any accountability mechanism built on disclosure principles, it should require a minimal chain of events that can be summarized in the following manner: (1) Data is published; (2) The data published reaches its intended public; (3) Members of the public are able to process the data and react to it; and (4) Public officials respond to the public’s reaction or are sanctioned by the public through institutional means. This simplified path toward accountability highlights the limits of the disclosure of information. Even in the most simplified model of accountability, while essential, the disclosure of data accounts for no more than one-fourth of the accountability process. [Note 1 - see below]

But what are the conditions required to close the accountability cycle? First, once the data is disclosed (1), in order for it to reach its intended public (2), a minimal condition is the presence of info-mediators that can process open data in a minimally enabling environment (e.g. free and pluralistic media). Considering these factors are present, we are still only half way towards accountability. Nevertheless, the remaining steps (3 and 4) cannot be achieved in the absence of citizen engagement, notably electoral and participatory processes.

Beyond Elections

With regard to elections as a means for accountability, citizens may periodically choose to reward or sanction elected officials based on the information that they have received and processed. While this may seem a minor requisite for developed democracies like the US, the problem gains importance for a number of countries where open data platforms have launched but where elections are still a work in progress (in such cases, some research suggests that transparency may even backfire).

But, even if elections are in place, alone they might not suffice. The Brazilian case is illustrative and highlights the limits of representative systems as a means to create sustained interface between governments and citizens. Despite two decades of electoral democracy and unprecedented economic prosperity in the country, citizens suddenly went to the streets to demand an end to corruption, improvement in public services and… increased participation. Politicians, themselves, came to the quick realization that elections are not enough, as recently underlined by former Brazilian President Lula in an op ed at the New York Times “(….) people do not simply wish to vote every four years. They want daily interaction with governments both local and national, and to take part in defining public policies, offering opinions on the decisions that affect them each day.” If transparency and electoral democracy are not enough, citizen engagement remains as the missing link for open and inclusive governments.

Open Data And Citizen Engagement

Within an ecosystem that combines transparency and participation, examining the relationship between the two becomes essential. More specifically, a clearer understanding of the interaction between open data and participatory institutions remains a frontier to be explored. In the following paragraphs I put forward two issues, of many, that I believe should be considered when examining this interaction.

I) Behavior and causal chains

Evan Lieberman and his colleagues conducted an experiment in Kenya that provided parents with information about their children’s schools and how to improve their children’s learning. Nevertheless, to the disillusionment of many, despite efforts to provide parents with access to information, the intervention had no impact on parents’ behavior. Following this rather disappointing finding, the authors proceeded to articulating a causal chain that explores the link between access to information and behavioral change.

The Information-Citizen Action Causal Chain (Lieberman et al. 2013)

While the model put forward by the authors is not perfect, it is a great starting point and it does call attention to the dire need for a clear understanding of the ensemble of mechanisms and factors acting between access to data and citizen action.

II) Embeddedness in participatory arrangements

Another issue that might be worth examination relates to the extent to which open data is purposefully connected to participatory institutions or not. In this respect, much like the notion of targeted transparency, a possible hypothesis would be that open data is fully effective for accountability purposes only when the information produced becomes “embedded” in participatory processes.

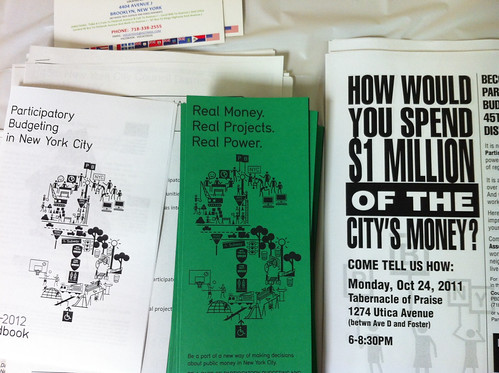

This notion of “embeddedness” would call for hard thinking on how different participatory processes can most benefit from open data and its applications (e.g. visualizations, analysis). For example, the use of open data to inform a referendum process is potentially a very different type of use than within participatory budgeting process. Stemming from this reasoning, open data efforts should be increasingly customized to different existing participatory processes, hence increasing their embeddedness in these processes. This would be the case, for instance, when budget data visualization solutions are tailored to inform participatory budgeting meetings, thus creating a clear link between the consumption of that data and the decision-making process that follows.

Granted, information is per se an essential component of good participatory processes, and one can take a more or less intuitive view on which types of information are more suitable for one process or another. However, a more refined knowledge of how to maximize the impact of data in participatory processes is far from achieved and much more work is needed.

R&D For Data-Driven Participation

Coming up with clear hypotheses and testing them is essential if we are to move forward with the ecosystem that brings together open data, participation and accountability. Surely, many organizations working in the open government space are operating with limited resources, squeezing their budgets to keep their operational work going. In this sense, conducting experiments to test hypotheses may appear as a luxury that very few can afford.

Nevertheless, one of the opportunities provided by the use of technologies for civic behavior is that of potentially driving down the costs for experimentation. For instance, online and mobile experiments could play the role of tech-enabled (and affordable) randomized controlled trials, improving our understanding of how open data can be best used to spur collective action. Thinking of the ways in which technology can be used to conduct lowered costs experiments to shed light on behavioral and causal chains is still limited to a small number of people and organizations, and much work is needed on that front.

Yet, it is also important to acknowledge that experiments are not the only source of relevant knowledge. To stick with a simple example, in some cases even an online survey trying to figure out who is accessing data, what data they use, and how they use it may provide us with valuable knowledge about the interaction between open data and citizen action. In any case, however, it may be important that the actors working in that space agree upon a minimal framework that facilitates comparison and incremental learning: the field of technology for accountability desperately needs a more coordinated research agenda.

Citizen Data Platforms?

As more and more players engage in participatory initiatives, there is a significant amount of citizen-generated data being collected, which is important on its own. However, in a similar vein to government data, the potential of citizen data may be further unlocked if openly available to third parties who can learn from it and build upon it. In this respect, it might not be long before we realize the need to have adequate structures and platforms to host this wealth of data that – hopefully – will be increasingly generated around the world. This would entail that not only governments open up their data related to citizen engagement initiatives, but also that other actors working in that field – such as donors and NGOs – do the same. Such structures would also be the means by which lessons generated by experiments and other approaches are widely shared, bringing cumulative knowledge to the field.

However, as we think of future scenarios, we should not lose sight of current challenges and knowledge gaps when it comes to the relationship between citizen engagement and open data. Better disentangling the relationship between the two is the most immediate priority, and a long overdue topic in the open government conversation.

Notes

Note 1: This section of this post is based on arguments previously developed in the article, “The Uncertain Relationship between Open Data and Accountability”.

Note 2: And some evidence seems to confirm that hypothesis. For instance, in a field experiment in Kenya, villagers only responded to information about local spending in development projects when that information was coupled with specific guidance on how to participate in local decision-making processes).