Medford/Somerville, MA – Young people have turned out in record numbers for the 2016 GOP primaries and caucuses. Now that Donald Trump is the presumptive Republican nominee, researchers at the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning & Engagement (CIRCLE) – the preeminent, non-partisan research center on youth engagement at Tufts University’s Jonathan M. Tisch College of Civic Life – today released an analysis of his level of support from young people during this primary election cycle. This briefing examines how Mr. Trump’s support from young voters stacks up with previous Republican nominees, as well as implications for the general election.

The briefing offers findings in response to several key questions:

How did Donald Trump do among young people who voted in the primaries?

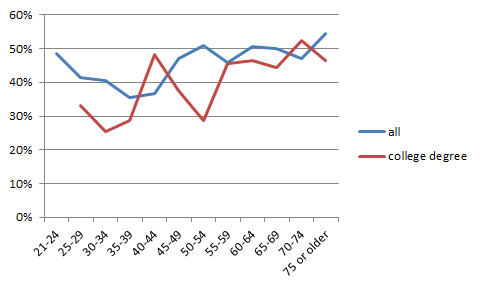

- Generally, Donald Trump has received a lower level of support from youth, ages 17-29, than from older voters, particularly those over 45: averaging roughly one-third of the youth vote vs. 43 percent of older voters.

- In the first 21 states for which youth data are available, Mr. Trump won 17 overall and received a plurality of youth votes in just 11.

- As the Republican field narrowed, young people who identified as or with Republicans showed greater levels of support for Mr. Trump in states like Pennsylvania and Indiana.

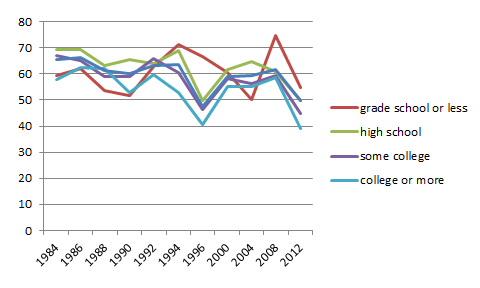

How does Trump’s youth support compare to that of previous Republican nominees?

- Mr. Trump has received a slightly larger proportion of estimated youth votes in the primary season than previous Republican nominees Senator John McCain (2008) and Governor Mitt Romney (2012).

- In 2016, both parties’ nominating contests remained competitive for many months, which may have driven youth turnout.

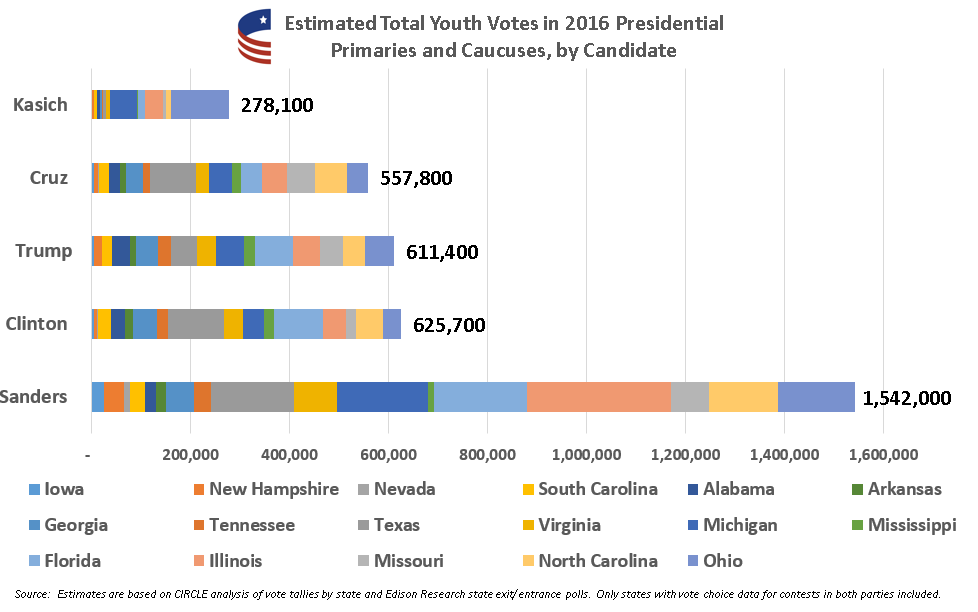

- While Republican youth have been underrepresented in recent primary and general elections, this year youth participation in the Democratic and Republican contests has been rather evenly split. Currently, in the states for which data are available for both parties, 55% of young primary participants have voted in Democratic contests, while 45% have voted in GOP contests.

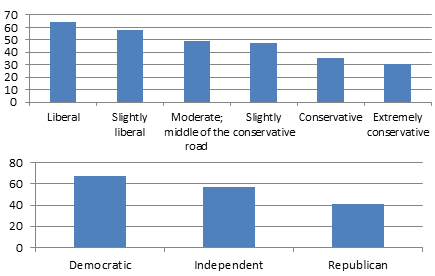

How do young people overall view Donald Trump?

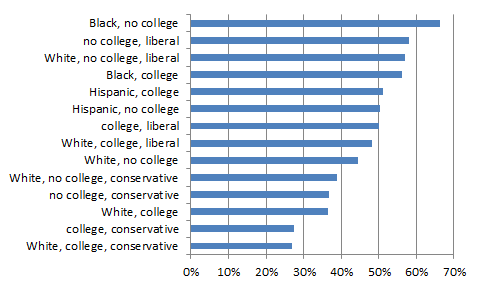

- As a whole, young people view Mr. Trump unfavorably, with young women and non-white youth, who together make up roughly 70 percent of the youth electorate, viewing him even more unfavorably; young people with less formal education have shown greater levels of support in the primaries.

- Our analysis shows that among “solid Republican” youth, 8 out of 10 are non-Hispanic Whites; and this group skews slightly male.

- Among all young eligible voters, 78% do not have a four-year college degree—whether because they have no college experience or because they are in college but have not yet graduated.

- Mr. Trump also performs well with young people who are disillusioned with the overall state of the country.

What are the potential implications for the general election?

- Two major factors may affect Donald Trump’s performance with young voters in November: education and ideology/party affiliation.

- Young people without a four-year college degree—one of Mr. Trump’s strongest constituencies among youth—tend to vote at higher rates in general elections than in primaries. However, their overall turnout is still fairly low. This could inform Mr. Trump’s campaign outreach strategy and suggests a need to mobilize a great deal of non-college youth to move the overall youth electorate in his favor.

- Consistent with the political polarization of the general electorate, about two-thirds of young people who participated in the Republican primaries identified as conservatives rather than moderates. However, like many young voters today, young Republican primary participants were less likely than older voters to identify with the Republican Party.

For CIRCLE’s full briefing, please see here. CIRCLE’s 2016 Election Center will continue to offer new data products and analyses providing a comprehensive picture of the youth vote, including a forthcoming analysis of the presumptive Democratic nominee Secretary Hillary Clinton. CIRCLE researchers also will provide insight into key states where young people have the potential to shape the 2016 general election, as rated in CIRCLE’s Youth Electoral Significance Index.