I’ve had deep connections to the UK since childhood and have always been committed to the idea of Britain in Europe. I believe that the UK has been much better off as a part of the EU, while the EU could benefit from particular British perspectives and institutions. For those reasons, Brexit saddened me.

However, I also believe in polycentricity. As a descriptive theory of the world, it says that there are (almost) always many centers of power, and they need not stack up neatly, with smaller, weaker units inside bigger and stronger ones. Jurisdictions and roles usually overlap and interrelate in complex ways.

As a reform agenda, polycentricity says that things work better when power is divided into many parts that partially overlap. Over-centralization is generally unwise.

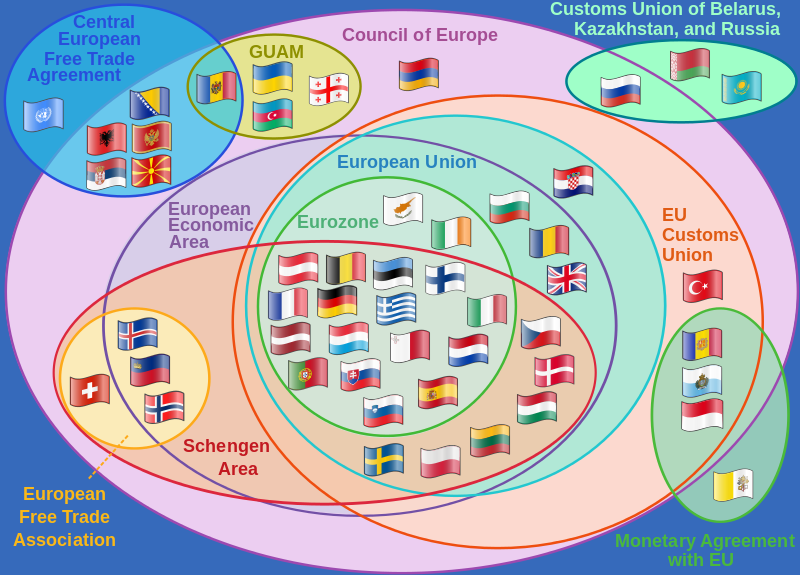

“Europe” is already polycentric in this sense. Here is one person‘s diagram of important treaties among European nations. The treaty groups overlap in a classic polycentric way.

This diagram is useful but far from complete. In addition to treaty arrangements, one could add other partnerships among nations, cities, companies, labor unions, universities, parties, professional groups, and more. Also, the image presents each nation as a unit, when many EU member states are federal or otherwise decentralized.

The picture is a little dated; the Union Jack will have to move outside of several circles where it appears above. However, the UK will not move outside of the polycentric network of Europe. Like it or not, Britain is “in.”

To British people who favor European integration, I would say: Brexit was bad. But you are still in Europe. The path forward is to encourage as much participation as possible in a wide range of cooperative ventures, whether among nations or among other kinds of entities. These cooperative activities should extend across Europe but not always be limited to the European continent.

To people who aspire to a federal Europe, I would say: Federalism, as implemented in republics like the USA, Germany, and Brazil, is one approach to combining centralization with decentralization. It assumes a Westphalian sovereign state that has ultimate power and attracts the deepest allegiance from all its citizens, with a neat tessellation of smaller and weaker units inside it that resemble each other and have similar relationships to the whole. This is by no means the only approach to making something large out of many smaller components. In the European context, federalism may have outrun its mandate and potential, at least for now. So everyone who wants to see Europe integrate should be willing to experiment with other overlapping associations.

To Euroskeptic Britons, I would say: You’re in Europe. You always have been, at least since prehistoric French people helped build Stonehenge. Sovereignty is an oversimplification, since power is always polycentric. By overestimating the importance of the national level of government, you have reaped a bunch of unnecessary problems and foreclosed some beautiful solutions, such as a borderless Ireland within the EU. Nevertheless, you and your children and your children’s children must belong to numerous networks and partnerships that cross the Channel. You should be working on making these partnerships work.

See also: Brexit: a personal reflection; modus vivendi theory; avoiding a sharp distinction between the state and the private sphere; British exceptionalism 2: the unique nature of the aristocracy; a range of federalism options for Israel-Palestine.