In recent weeks, we commoners have lost three great visionaries. Each spawned robust institutions and movements to carry their visions forward; the continuing vitality of their projects confirm that their spirits remain very much with us. We should pause to reflect on and celebrate their towering contributions.

I'm talking about the British architect/philosopher Christopher Alexander, who invented the "pattern language" approach to urban design and building; Edgar Cahn, the creative American legal activist who invented timebanking and cofounded Antioch School of Law; and Gustavo Esteva, the post-development thinker and founder of the Universidad de la Tierra in Oaxaca.

Christopher Alexander's Fearless Exploration into Aliveness and Design

I remember encountering Christopher Alexander's seminal book, A Pattern Language, in the late 1970s, a cultural moment that was erupting with all sorts of mind-blowing ideas. Alexander wanted to know why certain designs in architecture and urban spaces were consistently used across cultures and history. These include the proportions of space in rooms....the placement of windows....the design of public squares... the popularity of cafes in cities....among dozens of other forms. What accounts for their timeless appeal?

Alexander and his coauthors came to see that beauty, grace, and spiritual satisfaction actually play vital roles in the design of everyday life and buildings. Certain designs embody aliveness! But that quality can only be seen through a certain prism, which is what Alexander set out to name and analyze. He called his method a pattern language.

A pattern, in Alexander's view, describes "a problem that occurs over and over again in our environment, and then describes the core of the solution to that problem, in such a way that you can use this solution a million times over, without ever doing it the same way twice."

Each solution is unique because the context of the problem -- the geography, culture, values, and history of the designers -- is always different. Yet there are regularities -- or patterns -- to be identified and studied. In A Pattern Language, Alexander identified 253 interrelated patterns in urban and building design.

As my late colleague Silke Helfrich and I began to think about the nature of commons as social systems, we saw how the pattern language methodology could help us explain how commons actually work -- because commons, like buildings, are not primarily about physical things. They are about the interactive social dynamics of humans as they engage with each other and the Earth.

Silke and I came to realize that there is no standard blueprint or prescriptive approach for explaining commons. Rather, each commons reflects its own creators' humanity and circumstances. It must organically grow over time, and thus reflect the cultural preferences, local conditions, etc. of that particular system. But patterns can help us identify the regularities and fractal similarities.

From 2002 to 2004, Alexander published a four-volume magnum opus, The Nature of Order, that summarizes his vision of how aliveness is imbued within buildings and the built environment. It's a longer presentation that can be summarized here (check out this Wikipedia summary). Let's just say that Alexander tried to explain how consciousness and spirit manifest themselves in physical structures like buildings (or commons). He saw the need to move beyond the mechanical, Newtonian mindset and reinterpret architecture as a cosmological act of creation -- a life process expressed through buildings and space.

Edgar Cahn: Inventing Institutional Systems of Care

I mourn as well the passing of Edgar Cahn, an American law professor who may be best known to commoners for creating Timebanking. An early commons colleague of mine, Jonathan Rowe, worked with Edgar to write Time Dollars, published in 1992. Its subtitle says it all: "The new currency that enables Americans to turn their hidden resource -- time -- into personal security and community renewal." (Time Dollars later became "Timebanking" as it went international.)

Timebanking is a service-barter system. People can earn one credit for every hour of service to someone (mowing a lawn, providing eldercare, etc.), and that credit can be used later to "buy" other services. In communities without much money -- e.g., the elderly and people with low-incomes -- Timebanking helps organize and mobilize people's care work. But it had a much deeper purpose as well -- to build new bonds of community and personal affection in a world decimated by market individualism and a culture driven by money.

The idea behind timebanking came from a place of deep compassion. As Edgar explained:

"There is a value in just 'being' who you are that systems do not create, cannot define or control, and may not necessarily satisfy what one wants," Edgar once said. "The freedom 'to be' is at the heart of those so-called inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Exercising those rights may need protection. But 'to be' means that one matters, that one's existence makes a difference."

Timebanking is a way for anyone, regardless of their talents or training, to make a positive difference in other people's lives, despite the countervailing pressures of the modern capitalist world.

Over the past twenty years, Timebanking has proliferated around the world in scores of contexts. Here, for example, is a profile of the Helsinki Timebank, which became so robust that the project attempted to persuade the city to let people pay their taxes with timebanking credits. (The city government rejected the idea.)

In the larger scope of Edgar's remarkable life, Timebanking was just one achievement. He was also an active force in starting a federally funded US system of legal services for the poor (Legal Services Corporation); spurring Native American tribes to fight for their sovereignty as nations within the US polity; and pioneering a new practice-based approach to legal education at Antioch School of Law (now the UDC David A. Clarke School of Law). Here are some further tributes to Edgar Cahn.

Gustavo Esteva: Encountering Life Beyond "Development"

It is painful to note, also, the loss of Gustavo Esteva, a Mexican philosopher, economist, activist and educator who made a big mark on his times, both within Mexico and in internationally. Based on his experiences among Indigenous peoples, as a guerrilla activist, a government official, and a disillusioned Marxist, Esteva saw firsthand the pathways of modern "development." Drawing on his varied experiences, he became an eloquent and ardent critic of it -- and a champion for more grounded forms of human agency and authentic ways of being.

After serving ten years as a top economic minister within the government, Esteva soured on statist politics and moved into the world of commoning in its various guises. After meeting the Catholic social critic Ivan Illich, Esteva became a fast friend, adopting many of Illich's critiques of capitalist modernity and championing the need for people to develop their own human agency and authentic ways of living. He became a fierce advocate for peasants, Indigenous peoples, and marginalized urban dwellers.

In this quest, Esteva rejected the idea that "reason" is the "ultimate horizon of intelligibility." For example, he explained that in modern life "reason became a substitute for God, without my knowing it; it became the ultimate referent, valid in and of itself. This new consciousness, typically Western for both believers and nonbelievers, presupposed a trust in reason that assumed it to be the objective and solid foundation of all human thought and behavior."

Esteva may be best known for his founding of Universidad de la Tierra (or Unitierra, 'University of the Earth'), based on the radical educational ideas of Illich and Brazilian philosopher Paolo Freire. Unitierra provides free learning opportunities, especially for young people who have not completed school or vocational training, to learn communally what they are interested in.

In the mid-1990s, Esteva became a friend and advisor to the Zapitistas movement in Oaxaca as they struggled against repression by the Mexican government. He wrote numerous essays and books, including Grassroots Postmodernism, The Future of Development, and the essay "The Zapatistas and People's Power." Here is a rich profile of Esteva's remarkable life. I am proud to say that Gustavo contributed an essay to Silke Helfrich's and my edited anthology, The Wealth of Commons. It was entitled, "Hope from the Margins," which is a wonderful summation of his life's work.

In recent weeks, we commoners have lost three great visionaries. Each spawned robust institutions and movements to carry their visions forward; the continuing vitality of their projects confirm that their spirits remain very much with us. We should pause to reflect on and celebrate their towering contributions.

I'm talking about the British architect/philosopher Christopher Alexander, who invented the "pattern language" approach to urban design and building; Edgar Cahn, the creative American legal activist who invented timebanking and cofounded Antioch School of Law; and Gustavo Esteva, the post-development thinker and founder of the Universidad de la Tierra in Oaxaca.

Christopher Alexander's Fearless Exploration into Aliveness and Design

I remember encountering Christopher Alexander's seminal book, A Pattern Language, in the late 1970s, a cultural moment that was erupting with all sorts of mind-blowing ideas. Alexander wanted to know why certain designs in architecture and urban spaces were consistently used across cultures and history. These include the proportions of space in rooms....the placement of windows....the design of public squares... the popularity of cafes in cities....among dozens of other forms. What accounts for their timeless appeal?

Alexander and his coauthors came to see that beauty, grace, and spiritual satisfaction actually play vital roles in the design of everyday life and buildings. Certain designs embody aliveness! But that quality can only be seen through a certain prism, which is what Alexander set out to name and analyze. He called his method a pattern language.

A pattern, in Alexander's view, describes "a problem that occurs over and over again in our environment, and then describes the core of the solution to that problem, in such a way that you can use this solution a million times over, without ever doing it the same way twice."

Each solution is unique because the context of the problem -- the geography, culture, values, and history of the designers -- is always different. Yet there are regularities -- or patterns -- to be identified and studied. In A Pattern Language, Alexander identified 253 interrelated patterns in urban and building design.

As my late colleague Silke Helfrich and I began to think about the nature of commons as social systems, we saw how the pattern language methodology could help us explain how commons actually work -- because commons, like buildings, are not primarily about physical things. They are about the interactive social dynamics of humans as they engage with each other and the Earth.

Silke and I came to realize that there is no standard blueprint or prescriptive approach for explaining commons. Rather, each commons reflects its own creators' humanity and circumstances. It must organically grow over time, and thus reflect the cultural preferences, local conditions, etc. of that particular system. But patterns can help us identify the regularities and fractal similarities.

From 2002 to 2004, Alexander published a four-volume magnum opus, The Nature of Order, that summarizes his vision of how aliveness is imbued within buildings and the built environment. It's a longer presentation that can be summarized here (check out this Wikipedia summary). Let's just say that Alexander tried to explain how consciousness and spirit manifest themselves in physical structures like buildings (or commons). He saw the need to move beyond the mechanical, Newtonian mindset and reinterpret architecture as a cosmological act of creation -- a life process expressed through buildings and space.

Edgar Cahn: Inventing Institutional Systems of Care

I mourn as well the passing of Edgar Cahn, an American law professor who may be best known to commoners for creating Timebanking. An early commons colleague of mine, Jonathan Rowe, worked with Edgar to write Time Dollars, published in 1992. Its subtitle says it all: "The new currency that enables Americans to turn their hidden resource -- time -- into personal security and community renewal." (Time Dollars later became "Timebanking" as it went international.)

Timebanking is a service-barter system. People can earn one credit for every hour of service to someone (mowing a lawn, providing eldercare, etc.), and that credit can be used later to "buy" other services. In communities without much money -- e.g., the elderly and people with low-incomes -- Timebanking helps organize and mobilize people's care work. But it had a much deeper purpose as well -- to build new bonds of community and personal affection in a world decimated by market individualism and a culture driven by money.

The idea behind timebanking came from a place of deep compassion. As Edgar explained:

"There is a value in just 'being' who you are that systems do not create, cannot define or control, and may not necessarily satisfy what one wants," Edgar once said. "The freedom 'to be' is at the heart of those so-called inalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Exercising those rights may need protection. But 'to be' means that one matters, that one's existence makes a difference."

Timebanking is a way for anyone, regardless of their talents or training, to make a positive difference in other people's lives, despite the countervailing pressures of the modern capitalist world.

Over the past twenty years, Timebanking has proliferated around the world in scores of contexts. Here, for example, is a profile of the Helsinki Timebank, which became so robust that the project attempted to persuade the city to let people pay their taxes with timebanking credits. (The city government rejected the idea.)

In the larger scope of Edgar's remarkable life, Timebanking was just one achievement. He was also an active force in starting a federally funded US system of legal services for the poor (Legal Services Corporation); spurring Native American tribes to fight for their sovereignty as nations within the US polity; and pioneering a new practice-based approach to legal education at Antioch School of Law (now the UDC David A. Clarke School of Law). Here are some further tributes to Edgar Cahn.

Gustavo Esteva: Encountering Life Beyond "Development"

It is painful to note, also, the loss of Gustavo Esteva, a Mexican philosopher, economist, activist and educator who made a big mark on his times, both within Mexico and in internationally. Based on his experiences among Indigenous peoples, as a guerrilla activist, a government official, and a disillusioned Marxist, Esteva saw firsthand the pathways of modern "development." Drawing on his varied experiences, he became an eloquent and ardent critic of it -- and a champion for more grounded forms of human agency and authentic ways of being.

After serving ten years as a top economic minister within the government, Esteva soured on statist politics and moved into the world of commoning in its various guises. After meeting the Catholic social critic Ivan Illich, Esteva became a fast friend, adopting many of Illich's critiques of capitalist modernity and championing the need for people to develop their own human agency and authentic ways of living. He became a fierce advocate for peasants, Indigenous peoples, and marginalized urban dwellers.

In this quest, Esteva rejected the idea that "reason" is the "ultimate horizon of intelligibility." For example, he explained that in modern life "reason became a substitute for God, without my knowing it; it became the ultimate referent, valid in and of itself. This new consciousness, typically Western for both believers and nonbelievers, presupposed a trust in reason that assumed it to be the objective and solid foundation of all human thought and behavior."

Esteva may be best known for his founding of Universidad de la Tierra (or Unitierra, 'University of the Earth'), based on the radical educational ideas of Illich and Brazilian philosopher Paolo Freire. Unitierra provides free learning opportunities, especially for young people who have not completed school or vocational training, to learn communally what they are interested in.

In the mid-1990s, Esteva became a friend and advisor to the Zapitistas movement in Oaxaca as they struggled against repression by the Mexican government. He wrote numerous essays and books, including Grassroots Postmodernism, The Future of Development, and the essay "The Zapatistas and People's Power." Here is a rich profile of Esteva's remarkable life. I am proud to say that Gustavo contributed an essay to Silke Helfrich's and my edited anthology, The Wealth of Commons. It was entitled, "Hope from the Margins," which is a wonderful summation of his life's work.

Early in 2021, I thought …

I now think that a combination of partisan self-interest and genuine support for Trump among some GOP politicians has prevented any serious reckoning. Also, for most Americans, this whole issue is not salient; only strong partisans on either side follow it. For instance, right now, the broadcast networks are barely covering the breaking news about Trump’s behavior after the election. In the absence of public attention, there is no incentive for Republican politicians to antagonize Trump, nor even for most Democrats to try to fix the problem.

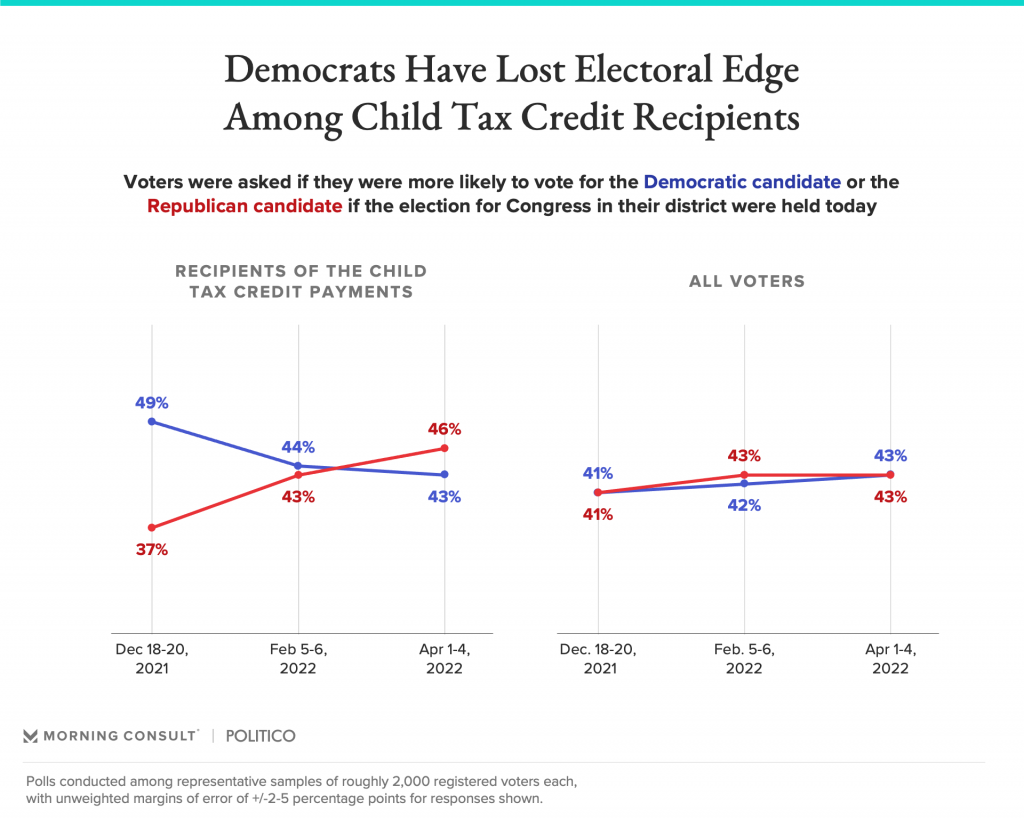

That would be good for Democrats and for the general idea that the government can be helpful. However, there is no sign that the funds were popular. It is possible that a core assumption of left-of-center politics is wrong: people don’t want this kind of help. But I suspect inflation simply ate it up, and voters blame the Biden administration for higher prices. The median household will spend about $4,500 more this year than last year to buy the same basket of goods, while the stimulus offered $1,400 per individual.

Speaking of inflation, I have no expertise on such matters, but I presumed the commentators were correct who blamed COVID-19 for temporarily disrupting supply and causing price spikes. Now it seems at least plausible that inflation is a major problem that will not abate without a recession.

Most importantly, such measures would save lives while allowing the economy to reopen safely. Meanwhile, they would pay dividends for the blue-state governors (including moderate Republicans) who closed schools and required masks, while embarrassing the most science-skeptical governors. However, Texas has had 2.9 cumulative deaths per thousand people from COVID-19 (basically at the national average); Florida has had 3.2; New York, 3.5; and New Jersey, 3.7. It is not clear which policies “worked” or how to weigh the significant costs against the possible benefits of policies like school closures. There is certainly no reason to think that governors like DeSantis will pay a political price (regardless of whether they should).

I never counted on a major social reform bill like Build Back Better to pass, since I doubted the Democrats had enough votes. I did harbor some hopes for the bill, based on the idea that the Trump fiasco, the COVID stimulus, and success in containing the pandemic would give Democrats momentum. Clearly, the opposite has happened. Although I strongly disagree with Democrats like Sen. Mark Kelly who are now running away from the bill, the psychology is clear enough. Recent events have undermined morale.

We have also experienced the exogenous shocks of Delta and Omicron plus Russia’s invasion of Ukraine (and Western sanctions). Selected experts predicted each of these events, but none was widely anticipated. Now the elections in Hungary and Serbia and the polling trend in France (where Le Pen is within the margin of error of Macron) add grounds for alarm.

There is plenty of work for all of us to do–assisting people affected by current crises and preventing future ones by educating and organizing. But I am not sure there is much anyone can do to change the immediate trajectory of global events. I can only hope that I will prove as mistakenly pessimistic in 2022 as I was naively optimistic a year ago.

This just needs dialogue, lyrics, and original music (presumably folk). It’s based on a bit of history plus plenty of invention.

Act 1, Scene 1: Silver King Mine, Utah (1914)

Striking miners sing of their suffering and despair. They are buoyed to see Joe Hill, a Swedish immigrant and union organizer, arrive. He leads them in a chorus of his song, “There is Power in the Union,” which raises their spirits. Hilda Erickson, age 20, a fellow Swede, approaches him and expresses her admiration for his courage.

Act 1, Scene 2: the same

Joe pulls fellow workers Sven Andersson and John G. Morrison aside to discuss what to do when hired guns come to break the strike. Morrison suggests they blow up the only bridge to the mine so that the goons can’t bring their heavy weapons with them. Andersson says he knows where they can steal some dynamite.

Act 1, Scene 3: Hilda’s family home, a humble homestead near Park City.

Joe arrives with flowers and asks Hilda out on a date the next weekend. After he leaves, she sings ambivalently. Maybe Joe would come to love her in time, but he seems to love the movement more–and death more than all.

Act 1: Scene 4: The sheriff’s office

The local sheriff meets with Morrison, who turns out to be a former police officer and now an undercover deputy. Morrison tells him that the Wobblies are planning acts of terror using dynamite. The sheriff orders Morrison to let them steal the explosives and then arrest them on the spot. Morrison sings of his anger that communist foreigners would try to subvert his community.

Act 2: Scene 1: Hilda’s home

Otto Appelquist, another Swedish immigrant, knocks on Hilda’s door, also bearing flowers. He sings of the life they could have together as his store thrives in the growing American West, the land of dreams. This song turns into a duet, with Hilda confessing the appeal of his vision even as she also admires Joe. She agrees to go on a date with Otto.

Act 2: Scene 2: A warehouse by night

Andersson and Morrison steal dynamite. Once Andersson has it in his hands, Morrison draws a pistol and tells him he’s under arrest. Andersson draws and fires, killing Morrison. Standing over the dead body, Andersson sings of his fear and announces that he will flee town immediately.

Act 2: Scene 3: Outside Hilda’s home, the same night.

Appelquist drops Hilda off at her door and sings of his love for her as he walks away. Joe Hill suddenly appears and demands that Appelquist leave Hilda alone. They argue heatedly. Joe picks up a shovel and brandishes it threateningly. Appelquist draws a pistol and shoots Joe in the chest; Joe staggers away.

Act 2: Scene 4: The same

Appelquist returns to Hilda and confesses in shame what he has done. She sings of her frustration with all violent, possessive men. She hopes that Joe survives and chooses not to turn Otto into the police.

Act 2: Scene 4: The sheriff’s office

The sheriff receives word by telephone that his deputy, John Morrison, has been killed. The phone rings again to let him know that the anarchist Joe Hill has staggered into a doctor’s office with a bullet wound to his lungs. He sings of his rage at Hill and expresses bitter satisfaction that the radical will now die for murder.

Act 3: Scene 1: The Utah Territorial Penitentiary, Salt Lake City

Orrin Hilton, a slick city lawyer, urges Joe to tell the jury who really shot him. Joe says he would never snitch, and besides, he doesn’t want to take the stand in his own trial. He sings that he will serve the revolution best as a martyr. What is one man’s life worth when millions starve with rags on their backs?

Act 3: Scene 2: A field outside of town

Otto admits that he is no hero, but he sings eloquent memories of the old country, Sweden, in summertime. Can’t they ever enjoy wild strawberries again? Meanwhile, Hilda sings a lament for Joe and commits to living a decent life with Otto.

Act 3: Scene 3: The Utah Territorial Penitentiary

Joe reads his last letter to “Big Bill” Haywood (“Don’t mourn–organize”) and sings his final testament: “My will is easy to decide / For there is nothing to divide. …” Men come and take him to be shot. As the commander counts, “Ready, aim …” Hill shouts, “Fire — go on and fire!” A ghostly chorus of workers sings Hill’s “The Preacher and the Slave” while Hilda and Otto watch, hand-in-hand.

We are fortunate to live near the Harvard Art Museums, and while visiting recently, I pulled open a drawer and saw one object inside: Joan Miro’s 1937 design for a fundraising stamp entitled “Help Spain” (Aidez L’Espagne). Miro’s handwritten text says, “In the current struggle, I see expired forces on the fascist side; on the other side, the people whose immense creative resources will give Spain a momentum that will astonish the world” (my translation).

Two years after this print was made, the Spanish fascists had won. For that reason, the image caught me short. I had to remind myself: sometimes the people do win; sometimes the creative forces prevail.