Jonathan Chait laments the use of the word “neoliberalism” to denounce Democratic Party leaders like President Obama and Hillary Clinton–even Elizabeth Warren–from the left. Chait tells a story that begins in the 1980s, when the word “neoliberalism” was “the chosen label of a handful of moderately liberal opinion journalists, centered around Charles Peters, then-editor of the Washington Monthly.” Chait began his own career with Peters and shares at least some of this group’s views. He feels attacked by those who call neoliberalism “the source of all the ills suffered by the Democratic Party and progressive politics over four decades, up to and (especially) including the rise of Donald Trump.”

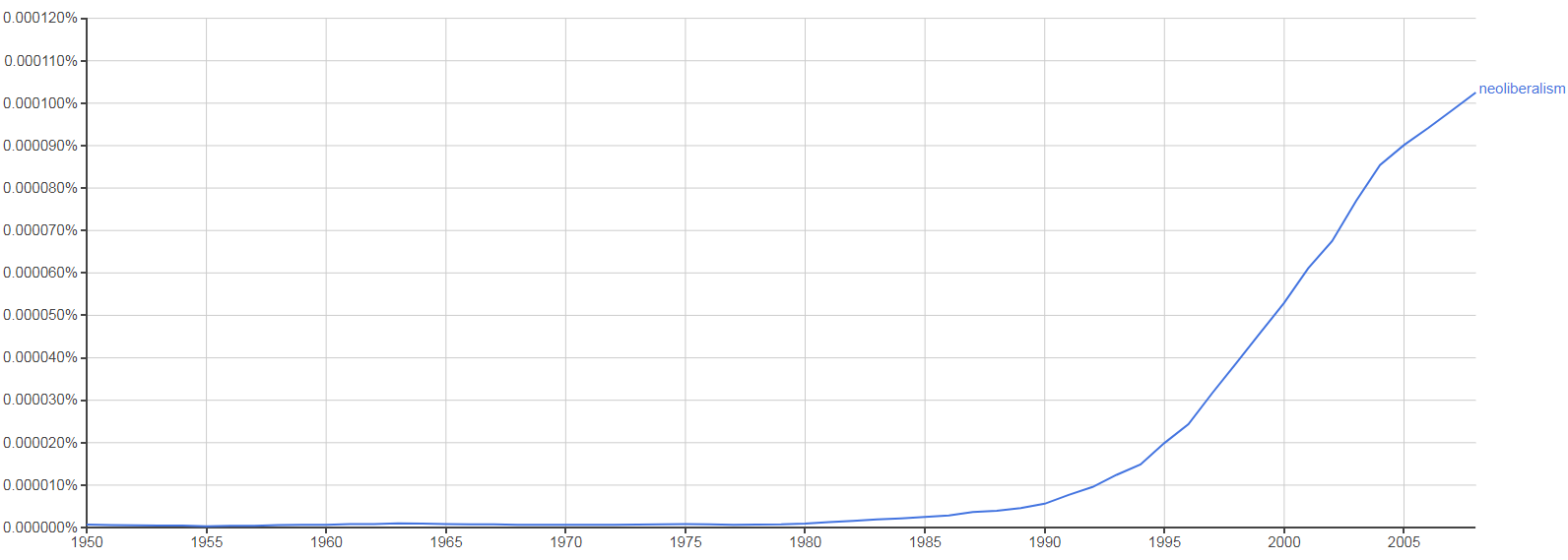

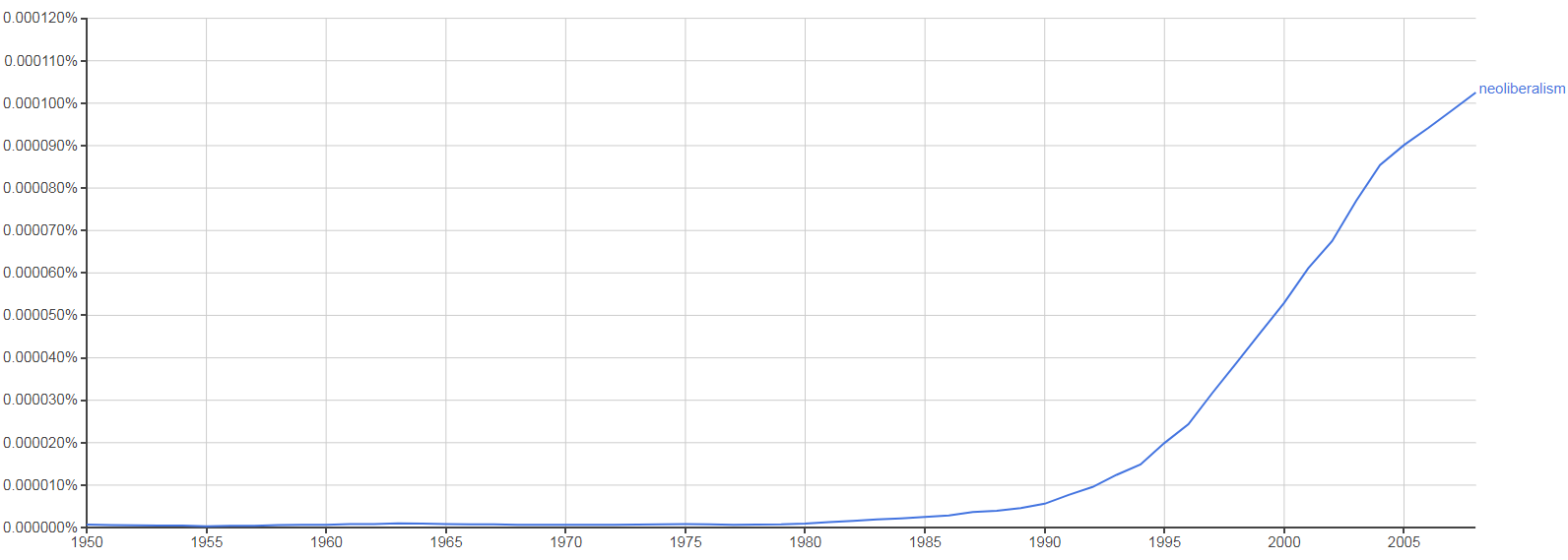

The word “neoliberalism” was virtually unused before 1950 and has rapidly become popular of late. But what does it mean?

“Neoliberalism” as a percentage of all the words in all English-language published books, 1950-2016, from NGram

In a reply to Chait, Mike Konczal distinguishes three kinds of neoliberalism, of which Chait’s is the first. Konczal argues that the left critique–a valid one–is against the second and third versions. All three have developed since 1980, probably contributing to the trend shown here.

Konczal’s three-fold distinction is better than the two-fold one I was going to propose before I read his piece, so I’ll follow his scheme. This is how I would define the three versions:

Neoliberalism I

In the 1980s, certain leaders of the Democratic Party (Charles Peters, Bill Galston, Bill Clinton, and others) argued that if you seriously evaluated social programs, you’d find that many didn’t work. Spending scarce resources ineffectively did the recipients no good and reinforced the voters’ sense that Democrats just threw money at problems. Some of these people were centrists, arguing with their party’s left. They called themselves “neoliberals” to assert a break with the positions of people like Walter Mondale, the supposed “paleoliberals.” However, in principle, their argument could appeal to leftists, who would reallocate funds from poorly performing programs to better ones. I can easily imagine a version of this agenda flourishing within a socialist system. It’s about measurement, accountability, managerial expertise, and innovation, which are features of modernity that have been quite influential on the left. If you “see like a state,” you will be interested in measuring impact and allocating resources to the most effective uses. The reallocations will be made by state agencies, which actually centralizes power.

Neoliberalism II

In the 1950s and 1960s, Keynsian economics reigned pretty much supreme on both sides of the Atlantic. Then stagflation delivered an intellectual blow, and soon Chicago School economists were making increasingly influential proposals for tax cuts, deregulation, and monetary responses to recessions. Their arguments were welcome to political and economic interests that never liked the taxes and regulations of the New Deal. The economists didn’t call themselves neoliberals, but that label made some sense in a global context, where “liberalism” typically means laissez-faire–what Americans call economic conservatism. Reagan and Thatcher were neoliberals in this sense, many continental European countries also moved in that direction, and the shift was dramatic in the Global South, partly because of pressure from the IMF and World Bank. The arguments tended to be utilitarian: if you cut taxes, then you will see more total wealth for the whole population. An authoritarian state, such as Pinochet’s Chile, could endorse these policies, in which case there would be a dramatic gap between political liberties and neoliberal economics. Indeed, some critics hold that this form of neoliberalism is mostly about using militarized state power to promote corporate economic interests.

Neoliberalism III

Since Victorian times, a social philosophy has been available that says market exchange is natural, whereas states are artificial; that exchanges of goods or labor for money manifest freedom; that success in a market reflects virtues (thrift, industry, creativity) rather than vices like greed; that governments are coercive, whereas market exchanges are voluntary; that people should be individually responsible for the consequences of their actions; that markets embody collective wisdom, whereas centralized planning is subject to massive error, etc. That philosophy was called “liberalism” ca. 1850. It gained momentum and picked up the name “neoliberalism” in the 1980s, although most actual proponents called themselves “libertarians,” “classical liberals” or (in America) “conservatives” rather than “neoliberals.” I have mentioned a lot of different ideas in this paragraph, and proponents need not endorse them all. However, the thrust here is neither pragmatic experimentation (as in Neoliberalism I), nor utilitarianism (Neoliberalism II), but a set of normative views about society and character. One of the greatest thinkers of the left, Michel Foucault, expressed some support for neoliberalism in this form, seeing it as potentially emancipatory. Foucault certainly wouldn’t have appreciated Neoliberalism I or II.

Put together, these three movements invoke a long list of ideas, and most people would refuse to endorse them all. Hardly anyone calls himself a “neoliberal”; it’s an epithet coming from further left on the political spectrum.

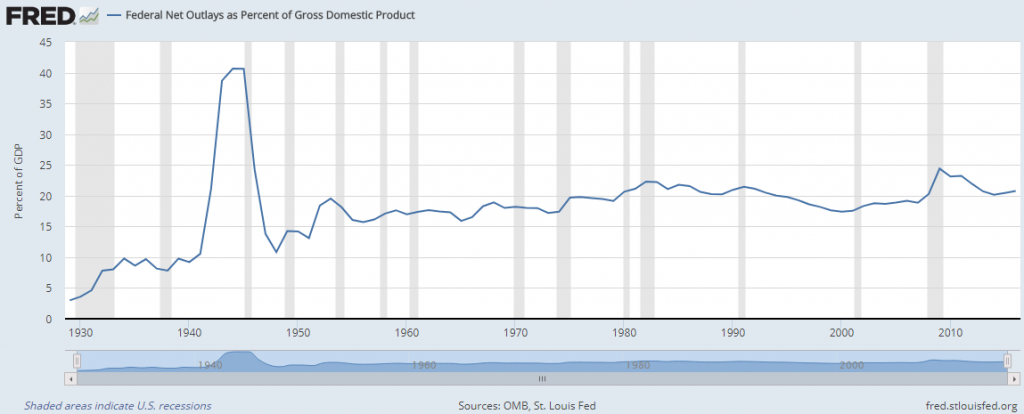

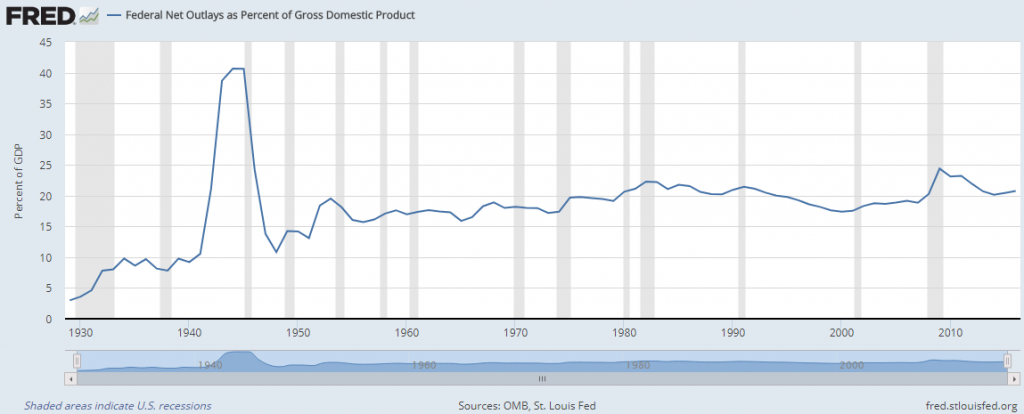

It’s not clear that we’ve really moved in a Neoliberal II direction. The federal government spends about 3 percentage points more of GDP today than it did in the 1960s, when the Great Society (and the War in Vietnam) were in full force.

However, there has definitely been a shift of rhetorical emphasis. The 1948 Democratic Party platform on which Harry Truman ran was unabashedly pro-government and critical of business. No modern Democrat would sound like that. They all order some of their dishes from column I, II, or III of neoliberalism’s menu.

Specifically, the Obama Administration loved concrete new policy interventions that could be rigorously evaluated. In 2o13, for instance, the administration proposed $200 million in a competitive pool for state governments that cut energy use and expanded HOPE (Hawaii’s Opportunity Probation and Enforcement scheme), which had performed well in evaluations. But they proposed to cut Social Security by $130 billion and Medicare by $380 billion. They didn’t like these cuts; they felt forced to offer them in a budget battle with Congress. But the result of expanding evaluated social programs while cutting entitlements would be Neoliberalism I.

Similarly, when modern Democratic leaders tout their superior economic management–Look at the GDP growth and stock market increases when we’re in charge!–they are making a utilitarian case for voting Democratic. It’s not exactly Neoliberalism II, because it doesn’t say: “Less government produces more net wealth.” Instead, it says: “A combination of competent management, fiscal prudence, targeted investments, and free trade produces more net wealth.” That claim may be true and reasonably popular, but it leaves a lot of space to its left, particularly when it carries a whiff of Neoliberalism III in the form of admiration for business leaders. It isn’t surprising, then, that a substantial number of people would want to criticize mainstream Democratic policy, and the word “neoliberalism” works pretty well for their purpose.

See also: Foucault and neoliberalism, Edmund Burke would vote Democratic, the core of liberalism, and what defines conservatism?