Monthly Archives: June 2017

CQ article on civic education

There’s always a steady trickle of articles about civic education, and I don’t post most of them, but I do recommend “Misinformed and Unschooled, Young People Are Failing in Civics” by Emily Watkins for CQ/Roll Call. Actually, the headline is a little too dire, since most kids face some kind of required course on civics that is graded, and most pass. But the content of the article is good. In particular, it highlights news media literacy as an objective, focuses on a real decline (class time devoted to social studies k-8), and gives an overview of the policy landscape, including the positive news of a current federal appropriation for civics.

NCDD’s Membership Drive Ends June 18th – Join Us!

We have reached the final THREE DAYS in the National Coalition for Dialogue & Deliberation’s membership drive. Our staff would love to see you join or renew your membership in NCDD before we end this drive on Sunday, June 18!

Here are three reasons why we (and others) think it’s worth joining NCDD:

1. Direct member benefits

As a member, you have access to numerous direct benefits that are worth much more than the cost of membership. Members get:

- Access to discounts on trainings and workshops, as well as a special registration rate at NCDD Conferences!

- First notice of news and opportunities, including jobs postings on the Making-A-Living Listserv, and the latest news through a special NCDD Member Newsletter.

- Access to a wealth of information and experiences through access to the archives of NCDD Confab Calls and Tech Tuesdays!

- A listing on the NCDD Member Map and Directory,

- And more! Check out ncdd.org/join for more details.

“Over the years I have reaped far more in benefits from NCDD than the tiny dues might warrant. NCDD has opened my eyes to new, powerful tools and wide-ranging perspectives that enrich my organizational work and make me a better facilitator. I’ve also gained some wonderful colleagues through NCDD. It was time to give back to an organization that has given me a great deal!”

– Juli Fellows, Ph.D.

2. Connections to others doing this work

One of the most commonly noted benefits of being a member of the NCDD network is the connections that are made between members. NCDD is unique in that our members represent a variety of professions, models for dialogue, and areas of focus or expertise. For many, becoming a member in NCDD means finding the people who best understand your work and who can help you develop and grow your practice. Imagine what you can gain from being in close communication with such a rich network!

“NCDD is the first place I turn if I need technical assistance with a dialogue issue/situation and it is the resource I share most often with others interested in learning more about dialogue. ”

– Cathey Capers, Wellspring Resources, Austin, Texas

3. Helping keep NCDD Sustainable

Your membership dues is essential to keeping NCDD sustainable. We’re a small organization, and rely on our members’ support in addition to grants and donations in order to keep this network strong and growing. Your membership dues goes directly to helping our staff continue to offer our programs and resources to you!

“I was ‘there at the beginning’, and I think that what you all are doing is so very important for our polarized, fractured world.”

– Jim Snow, NCDD Founding Member

“More than ever now we have to support the work each and all of us are doing in the dialogue and deliberation field – or we’re doomed. As I see it, NCDD is our lodgepole.”

– Deborah Goldblatt, Director, World Café Services, World Café Community Foundation

We hope you’ll consider joining or renewing your membership in NCDD by Sunday, June 18th, when our membership drive ends. We appreciate your continued support and look forward to all we can do together going forward!

Engaging Ideas – 6/16/2017

saving Habermas from the deliberative democrats

“God save me from the Marxists”–attributed to Karl Marx

Jürgen Habermas is often presented as the master theorist of deliberative democracy, the author who believes that a society should approximate an “ideal speech situation” in which “the only force is the force of the better argument.” People apply his theory by creating deliberative fora, such as citizen’s juries or Participatory Budgeting processes, that approach an ideal speech situation. People criticize him for being utopian or overly rationalistic.

There is some basis for this interpretation of Habermas, but it overlooks that he is a sociologist with an abiding interest in the big Systems of a modern polity: markets, firms, legislatures, courts, unions, and the like. He understands modernity as a process of differentiation in which institutions that have diverse organizational logics and incentives arise and interrelate. I haven’t encountered a point at which he advocates creating ideal participatory fora and adding them to the mix of social institutions (although he may have done so somewhere in his voluminous works). What he does advocate is social movements, especially the “New” movements that have arisen since the 1970s, which he understands as efforts to resist the encroachment of the state and the market on everyday life. He names, as examples, squatter movements that occupy houses in German cities, and anti-tax protests. He argues that these movements revivify the public sphere by forcing the public to debate the proper role of state and market in relation to private life. A better speech situation results as a byproduct of contentious politics.

The New Social Movements are not deliberative fora to which representative citizens are invited to discuss public issues and reach agreement on policies. Instead, they combine “discourse” with a whiff of tear gas. I think they are needed for a full appreciation of Habermas.

See also: Ostrom, Habermas, and Gandhi are all we need; Habermas and critical theory (a primer); the New Social Movements of the seventies, eighties, and today

NCDD Orgs Respond on How to Save American Democracy

As we grapple with a quickly changing political environment, many are struggling with the current state of American democracy and what are the best steps to repair our damaged system. Over the course of the year, several writers have expressed their beliefs that the way to improve our political system is to reduce public participation and increase political intermediaries/institutions.

In a direct response to these viewpoints, NCDD member org Healthy Democracy, recently published the article on their blog, Actually, More Public Participation Can Save American Democracy, which can be found here. The Deliberative Democracy Consortium, also a NCDD member org, wrote an immediate follow-up piece inviting the dialogue, deliberation, and public engagement community to respond to these claims and the writers themselves. For information on how to send your responses, read the DDC’s article on their blog here.

The article from Healthy Democracy can be found below or read the original on their blog here.

Actually, More Public Participation Can Save American Democracy

Lee Drutman of the New America Foundation, writing on Vox.com’s Polyarchy blog, makes a bold statement: more public participation isn’t the answer to our political woes because the reasonable, civically-minded voter is a myth. This is the latest in a trend of articles analyzing American politics and the role of citizens, beginning with Jonathan Rauch’s sprawling analysis for the Atlantic of our political system and its populist weaknesses.

Lee Drutman of the New America Foundation, writing on Vox.com’s Polyarchy blog, makes a bold statement: more public participation isn’t the answer to our political woes because the reasonable, civically-minded voter is a myth. This is the latest in a trend of articles analyzing American politics and the role of citizens, beginning with Jonathan Rauch’s sprawling analysis for the Atlantic of our political system and its populist weaknesses.

Fortunately, Mr. Drutman’s analysis is narrowly focused and should not discourage those of us who have broader imaginations about democracy and the power of an active citizenry. Public participation is not limited to voting for or against representative policymakers, as Drutman asserts. Rather, civic life is a rich ecosystem of opportunities to participate in our grand experiment in self-governance. The individual voter is the building block of democracy. Civically-minded wise Americans exist across the land, and they are doing good, important work in their communities.

Drutman’s article relies on a series of assumptions that are, at the very least, not the whole picture. They are based largely on assumptions that Jonathan Rauch and Benjamin Wittes make in their recent Brookings paper advocating for an increased role of political intermediaries and a decrease in direct democracy. In their world, participation in politics is limited to the election of representatives; the sole result of a citizen exerting their political wisdom is to vote out politicians who prioritize interest groups over the people; and, finally, making politicians serve the people is the end goal of public participation. But in reality, citizenship and public participation encompass a wide array of powers and responsibilities. To be clear, I don’t take issue with the negative impacts of unbridled, reactive populism. Rather, I see clearly the vast and largely untapped potential of democratic wisdom at the citizen level.

The mythical citizen

Drutman articulates others’ assertion that there is a mythical wise citizen who will save our democracy by influencing politicians to serve the people. This citizen is “moderate, reasonable, and civic-minded” and if given more power would compel politicians to behave differently. It would indeed be naïve to assume that this magic citizen would influence American society so greatly that they could change the fundamental behavior of politicians. In that way, the author’s objection to this mythical citizen is easy to make.

And I agree that waiting for a perfectly reasonable, moderate, and civically minded voter to fix our Republic is a flawed strategy. Thankfully for all of us, public participation is much broader, deeper, and more creative than that. The various mechanisms of public participation build civic literacy, increase citizen power through knowledge and interaction with our political systems, and build bridging social capital among disparate groups. There are positive downstream impacts on our local, state, and national communities that come from citizens engaging in their communities in a meaningful way.

Drutman also addresses the role of political intermediaries. These intermediaries, which he defines as “politicians, parties, and interest groups” are the people who help people recognize what their interests are through cues. But this group is depressingly limited, and strikingly partisan. It ignores faith leaders, universities, media, community groups, advisory groups, citizens’ juries, and local government engagement folks. These groups, many of which are nonpartisan, provide moral leadership, knowledge, and granular information about voter interests that Drutman’s definition of intermediaries ignores.

The power of regular citizens

Drutman’s article forecloses the citizen’s ability to participate in democracy in ways that consider tradeoffs and the long-term view. There is a glimpse of possibility in his discussion of hybrid systems, citing Rauch and Wittes’s assertion that ““better decisions” come when specialist and professional judgment occurs “in combination with public judgment.” Unfortunately, Drutman rejects the concept by conjecturing that hybrid systems are not possible because they would not have a clear person who is “in charge” and holding the power. In fact, the entire field of democratic deliberation is devoted to creating hybrid systems that connect citizens with policy experts and allow them the time, space, and information to carefully consider policy choices.

Of course, power is held both formally and informally, and differently depending on the situation. In a classic representative system, elected policymakers have the ultimate power, and they can gather input in various forms. There are also stakeholder processes where groups can be given very strong recommending power, to the point where it would be politically infeasible to reject their advice. There is also direct empowerment of citizens, such as through ballot initiatives and referenda, where a majority vote of the people makes policy. Drutman’s claim that “voters are not policymakers” is simply not true in states, cities, and counties with direct democracy.

Creative solutions

In all of these cases, there are opportunities to merge technical expertise with citizen participation. The example with which I most familiar is the Citizens’ Initiative Review. This process, which was developed by Healthy Democracy, is a hybrid system in which a microcosm of representative citizens (reasonable, moderate, and civic-minded, by the way) examines a ballot measure. They draw upon the arguments of partisan intermediates (advocates for and against the measure) and the input of independent policy experts. Their goal is to provide to their fellow voters a clear statement that outlines the key facts about a ballot measure as well as the best arguments on each side.

The result of public participation in the Citizens’ Initiative Review is an artifact that can be used by voters to make civic-minded decisions when participating in direct democracy. The knowledge that a group of fellow citizens spent four days sorting through the issue on their behalf is an inspiring service, one that can compel not only the people in the room but those who read their statement and appreciate the service to be more civic-minded and engaged in their own lives.

Research by scholars in the political science, communication, and government fields affirms that the Citizens’ Initiative Review process is democratic, deliberative, and unbiased. Their analyses find that Citizens’ Statements are highly accurate and are a reliable source of information for voters. They also find that voters actually do use the statement when casting their ballots, and that voters who read the statement have more knowledge and are more confident in their knowledge.

This piece is not intended to be an advertisement for the Citizens’ Initiative Review, but the fact is that reforms like it are rare and most folks do not have the opportunity to witness these processes and their results. In our unique position as a deliverer of these reforms, we see the extraordinary transformation that regular people undergo when called to serve their fellow voters in this way. The vast majority of citizen participants leave with a better understanding of democracy, political values, and policy analysis—not to mention a deeper understanding of the policy topic under study.

It should be noted that one reason these reforms are rare is because they disrupt the work of partisan intermediaries who would prefer to deliver information to voters through a lens that suits their own ends, often at the expense of accuracy. In a refrain familiar to many political observers, partisan intermediaries’ assessment of the value of nonpartisan intermediaries corresponds closely with how well the information produced via nonpartisan means supports their partisan ends.

Democracy starts–but does not end–with politics

You see, citizen participation takes many forms. And participating in democracy does not fit neatly in the world of policy and politics. It is a common lament recently that hyperpartisanship has led to two Americas, and that our problem is that we refuse to talk to one another. Well, the first step to breaking down hyperpartisanship is to personally know people with politics that oppose your own. Any action that builds bridging social capital (social capital across heterogeneous groups) is an act of democracy. Then, when our democratic systems are stressed, we can draw upon that social capital for resilience. If we can see the other side as people, and don’t demonize, dehumanize, and disregard them based on partisan cues, we can stay engaged in democracy with one another.

In the close of his piece, Drutman calls on us to abandon the search for the mythical average citizen and seek an alternative. Since the author fails to articulate an alternative, I offer one here: let us expand our understanding of public participation to include the multitude of civic actions that add value to our democracy.

We can start in the realm of policymaking and politics with deliberative democracy. Well-designed deliberative processes (see the National Issues Forums, citizens juries, and the Citizens’ Initiative Review, among others) give voters a structured container to consult experts, consider tradeoffs, and deliberate the merits, consequences, and underlying values of policy choices. These processes take time, patience, and resources, but it is a worthwhile investment in the health of our democracy.

Let’s also work to build social capital through community work. A bank of social capital can give us the tools and relationships to better consider policy tradeoffs and impacts to our communities in the future. Additionally, an expanded conception of public participation gives voters opportunities to grow into more civically literate people. Not only can they better understand and act on their interests, they will be more likely to consider political problems creatively if they choose to enter representative politics. These kinds of programs are all around us. See Community Oregon, our experiment in building statewide urban-rural social capital in the state of Oregon, as well as other organizations that bring different types of people together to build connections across differences (e.g. Everyday Democracy, The Village Square, and many others).

The mythical citizen is all around us. She sings in a choir, volunteers her time, helps her neighbor with homework, and teaches her grandchild about the branches of government. She is doing democracy in her everyday life. She is serving her fellow citizens. She is our Plan B.

You can find the original version of this Healthy Democracy blog article at: https://healthydemocracy.org/blog/2017/06/13/actually-more-public-participation-can-save-american-democracy/

To respond to this article via the Deliberative Democracy Consortium blog, click here: http://deliberative-democracy.net/2017/06/15/we-invite-you-to-respond/

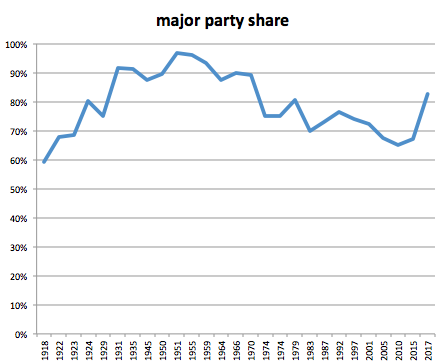

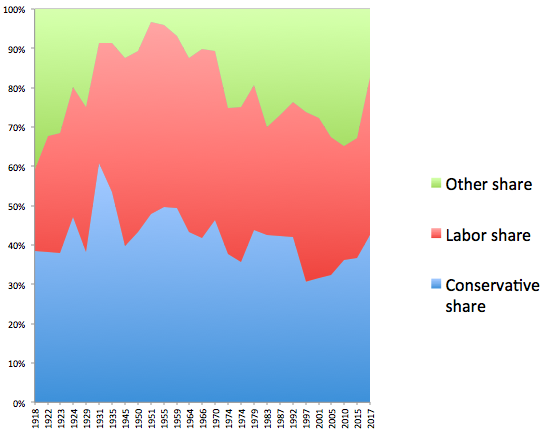

does the UK election show a return to two-party rule?

A May 2016 article in the Financial Times was headlined, “British politics has broken out of the two-party system.” The lead explains:

Politics has fragmented. London’s choice of Sadiq Khan as mayor grabbed the headlines — and rightly so. But the local and regional elections across the UK carried a broader message. British politics has broken out of the familiar framework of the two-party system. As in much of the rest of Europe the old rules are being discarded.

Provisionally, it seems the 2017 election results tell the opposite story. Here’s a hypothesis about what happened in Britain last week:

- Elections based on single-member districts tend to produce two-party systems, because votes for parties other than the top two are seen as “wasted.” The exceptions occur when regional parties are able to win majorities in their home areas.

- Given two parties, over time, people tend to split their votes about 50/50. If one party has a big advantage, that’s a disequilibrium; soon some demographic or identify groups migrate to the other party to even it out. Voters use party labels as heuristics and are not mainly affected by the specific policies or personalities on offer in a given campaign. That each party will get 50% of the vote is a pretty good guess.

- Britain avoided a two-party system for parts of the 20th century, but the 2017 election saw the duopoly return. That’s why, despite May’s poor performance and Corbyn’s arguably radical views, each got closer to 50% of the vote than their predecessors had for decades.

This second graph breaks it down by party:

Sources: The Guardian for the 2017 vote tallies so far. The UK Electoral Commission for historic data. Analysis is my own.

David Fleming’s “Surviving the Future”

Critiquing problems is far easier than imagining credible alternative futures. That seems to be the biggest problem in our political culture today: a colossal failure of imagination. I was therefore pleased when a new friend introduced me to the writings of David Fleming, an iconoclastic British thinker about economics, the environment, and culture who had roots in the British Green Party and Transition Town movement, among other circles.

Fleming worked for thirty years to produce a massive book Lean Logic: A Dictionary for the Future and How to Survive It, which was finished just before his death in 2010 and published by Chelsea Green in 2016. Many core themes of that book were skillfully distilled (by his colleague Shaun Chamberlin) into a shorter, more readable paperback, Surviving the Future: Culture, Carnival and Capital in the Aftermath of the Market Economy.

Fleming, one of the earliest to warn about Peak Oil, argues about the decline of the market economy with the rigor of an economist, ecologist and physicist. But what really sets him apart is his understanding that those things are intimately related to social organization and human culture. He realizes that the needs and wants engendered by capitalism will inevitably change as a society kept afloat by cheap fossil fuels falls apart.

What will society look like in the aftermath of this world? Fleming believes that we will rediscover and invent a life of place and play – a world in which the traditions of carnival, gift culture and a sense of place re-emerge. The post-market culture will also be a place where small-scale, local activities make sense again. Once large infrastructures become too costly to maintain, we will likely build systems that restore elegance and beauty to a place of honor, and that honors local judgment and direct participation in one’s life.

One of the invisible downsides to the modern economy is the huge layer of intermediary structures – roads, electrical grids, landfills, administrative systems – that are needed to keep “the economy” going and thereby produce the countless things we want or need. This has led to what Fleming calls the “intensification paradox.” While massive infrastructures may help boost productivity and sheer output, economic growth all intensifies our need for costly, fixed intermediate goods. This inevitably results in less efficiency and greater complications – at the same time that the expense of maintaining such systems rises.

This is why simply consuming less on an individual basis is not enough – the intermediate infrastructures still need to be sustained. Alternative, more localized systems need to be invented. “The system” conspires to keep itself afloat even if aggregate consumer demand declines because there are few practical alternatives.

Therefore, how to jump the rails to a different system – what Fleming calls the “lean economy” – is the big challenge.

A Lean Economy is about “maintaining the stability of an economy which does not grow,” writes Fleming. “Its institutions are designed as essential means to manage and protect its small scale.” How might this be done?

“One way to do so is by sharing out the work with restrictions on working time (as was required through the medieval period). Another is to absorb spare labour with standards of practice – such as organic production – which combine labour-intensive methods with other benefits such as high quality and low environmental impact…..Or supply goods for the purpose of destroying them, or to produce goods of monumental extravagance (pyramids, cathedrals, carnival…).”

As this passage suggests, Fleming is exploring a radical shift in our economy. He realizes that when the market economy inevitably fades and the state services and regulation are no longer affordable or minimally effective, we will need to draw upon social order and culture to fill the void.

If markets cannot provide a measure of social cohesion, we will need to look to new types of community institutions – dare we say, commons – to provide effective forms of self-governance and provisioning. In Lean Logic, Fleming devotes six pages to discussing the commons as a solution strategy.

Instead of looking to market consumerism and pop spectacle as unifying forces for our culture, the Lean Economy “will depend for its existence on a deep foundation in culture…..Only in a prosperous market economy [now jeopardized by Peak Oil and climate change, among other things] is it rational to go confidently for self-fulfillment, doing it on your won without having to worry about the ethics and narrative of the group and society you belong to.”

Fleming is bold enough to predict that it won’t be hard to move away from our market-based civil society; that will fall away so fast that we will find it hard to believe it was ever there. The task, on the contrary, is to recognize that the seeds of a community ethic – and indeed, of benevolence – still exist. It is to join up the remnants of local culture that survive, and give it the chance to get its confidence back.”

Surviving the Future is no doctrinaire manifesto or doomsday prophecy. It is, rather, a calm analysis written with good humor and a sense of life’s mysteries, joys and tragedies. For example, he talks about “The Wheel of Life” – a way of thinking about the life-cycle of a complex living systems. He explains environmental ethics as a matter of understanding laws of nature that, if not obeyed, “will in due course destroy,” albeit perhaps with time delays, non-linear links, and large and horrible amplifications of small acts.

Fleming calls for shifting our mindset from a taut, tense, and competitive economy to one that intentionally builds in “slack.” With the seeming inefficiencies of a slack system, one can have greater choices in how to use one’s time, rather than be locked into a market system that revolves around money and thus the maximum earning of money. In the same spirit, Fleming takes on The Rationalist, who “has no time for detail and repair, / Of loyalties and doubt he has no notion, / His certainties and sameness everywhere. / No meeting-up in conversation there.”

Fleming’s editor, Shaun Chamberlin, hastens to note that Fleming is not making predictions about the future (despite a considerable amassing of evidence), but rather possible and even likely scenarios. Serious People of mainstream political life are likely to scoff at a book that considers “the aftermath of the market economy.” But that’s a predictable response from people living in the penthouse of that (endangered) economic system or unwilling to think about big, long-term dynamics. On the ground, where millions of people actually live, the structural deficiencies of neoliberal capitalism are all too real, right now, and the existing system is not likely to self-reform itself.

Fleming opens some doors that few economists, political leaders and advocacy organizations dare to walk through. But his thoughtful, humanistic approach is a welcome tonic and rich with insights. Surviving the Future certainly expanded my appreciation for a future that is already arriving.

The Florida Joint Center for Citizenship Needs Your Help!

Please Donate Now If You Can Help!

The Governor recently vetoed all funding for the Lou Frey Institute, the parent organization for the Florida Joint Center for Citizenship, Civics360 and the Partnership for Civic Learning.

Did you Know?

- Teachers that use FJCC curriculum resources have seen an increase in assessment scores by 25%.

- Last year, FJCC staff delivered face-to-face professional development to over 1,000 civics teachers.

- Since August 2016, FJCC staff supported over 5,000 teacher accounts and over 94,000 hours of online civic learning for middle school students.

- Since March 2017, Civics360 was launched and has provided civics instruction and resources to over 20,000 civics students

Please help us so that we can continue supporting Florida’s, and the nation’s, teachers and students. Questions can be sent to me at any time!

Please Donate Now If You Can Help!

A Message from NCDD Board Chair Martin Carcasson

I wanted to take an opportunity to make another appeal to everyone to consider supporting NCDD by becoming a dues-paying member. As you’ve likely read, NCDD is changing its membership structure in order to build capacity in the organization. Effective June 19, all members will need to have their dues current to continue receiving member benefits and remain listed on the member map and directory.

As the current chair of the NCDD Board of Directors, I can tell you we struggled with this decision. We want to keep NCDD as open and accessible as possible, which is why we’ve traditionally had open membership without required dues (dues were optional). But as we continue to work to create capacity to address to the troubling hyper-partisanship of our times, we recognized that we needed more stability in the organizational structure to accomplish our work. NCDD had to grow up a little, and have a more consistent funding stream, particularly for our leadership positions. Once we establish the new structure, Courtney and Sandy should be able to focus so much more on doing the work and building, improving, and serving the network rather than searching for the dollars to cover their salaries.

As the current chair of the NCDD Board of Directors, I can tell you we struggled with this decision. We want to keep NCDD as open and accessible as possible, which is why we’ve traditionally had open membership without required dues (dues were optional). But as we continue to work to create capacity to address to the troubling hyper-partisanship of our times, we recognized that we needed more stability in the organizational structure to accomplish our work. NCDD had to grow up a little, and have a more consistent funding stream, particularly for our leadership positions. Once we establish the new structure, Courtney and Sandy should be able to focus so much more on doing the work and building, improving, and serving the network rather than searching for the dollars to cover their salaries.

I do hope you see the value in supporting NCDD. Yes, there are member benefits, but above all I hope people see this as a contribution to an organization whose work has never been as important as it is now. At a time when polarization and cynicism is tearing the country apart, those of us in NCDD know we have better ways of engaging the tough issues that actually bring people together. We also know that despite all the rancor, people do yearn for authentic engagement, and prefer that to the noise when given an opportunity.

I first became connected with NCDD in San Francisco in 2006. I don’t actually remember how I initially heard about the conference, but I was in the process of getting the Center for Public Deliberation started at Colorado State, and made it out to the coast to hopefully learn some useful skills. What I actually found was my tribe. An incredibly diverse group of people who saw the world like I saw it, passionate about making a difference and catalyzing change, but recognizing that the best way to do just that was by focusing on changing the conversation and giving people real opportunities to engage each other genuinely. I hope you see NCDD through a similar lens, and will help us expand and solidify our work by supporting the organization moving forward as an NCDD member.

Martin Carcasson

Director, CSU Center for Public Deliberation

Professor, Communication Studies at Colorado State University

Chair, NCDD Board of Directors