Monthly Archives: September 2015

Pope Francis and the Struggle for Democracy

Civic Renewal: A Webinar with Peter Levine and Joan Blades

The report discusses the leadership of the movement, the perspective of citizens, and ways in which the movement can continue to grow and succeed. I encourage you to check out the report. Following this week’s webinar, I will be sharing my own thoughts, and look forward to hearing yours. You can read the report here.

The report discusses the leadership of the movement, the perspective of citizens, and ways in which the movement can continue to grow and succeed. I encourage you to check out the report. Following this week’s webinar, I will be sharing my own thoughts, and look forward to hearing yours. You can read the report here.

Did I mention a webinar? That’s right! There will be a webinar on Wednesday, 23 Sep at 2pm to discuss the report, featuring Peter Levine and Joan Blades of the National Coalition for Dialogue and Deliberation. It will be worth your time, and as a reminder, it is free and open to the public, but they do request that you register in advance! It will no doubt be as enlightening as the report.

Civic Renewal: A Webinar with Peter Levine and Joan Blades

The report discusses the leadership of the movement, the perspective of citizens, and ways in which the movement can continue to grow and succeed. I encourage you to check out the report. Following this week’s webinar, I will be sharing my own thoughts, and look forward to hearing yours. You can read the report here.

The report discusses the leadership of the movement, the perspective of citizens, and ways in which the movement can continue to grow and succeed. I encourage you to check out the report. Following this week’s webinar, I will be sharing my own thoughts, and look forward to hearing yours. You can read the report here.

Did I mention a webinar? That’s right! There will be a webinar on Wednesday, 23 Sep at 2pm to discuss the report, featuring Peter Levine and Joan Blades of the National Coalition for Dialogue and Deliberation. It will be worth your time, and as a reminder, it is free and open to the public, but they do request that you register in advance! It will no doubt be as enlightening as the report.

we are hiring!

Come work on my team. We actually have two new jobs posted, one for a graduate student. Click the links for considerably more information about both.

The Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE) is a leading research center that studies young Americans’ civic development and participation. CIRCLE is the premier source of information—facts, trends, evaluations, and best practices—related to youth civic learning and engagement. CIRCLE shares the results of its research with policy makers, practitioners, journalists, and scholars in various disciplines.

CIRCLE is seeking a full-time Researcher to conduct research and to help manage some of CIRCLE’s research and evaluation projects. Reporting to the Director of CIRCLE and based on the Medford/Somerville Tufts University Campus, the Researcher will work as part of the CIRCLE team on CIRCLE products and activities. The Researcher will also interact with a larger group of colleagues at Tisch College, and will be expected to participate in various college-wide initiatives such as college-wide events and assistance with student program evaluations. Specific responsibilities include:

- Serving as an Researcher on a range of research projects that may include secondary data-analysis, literature reviews, field experiments, program evaluations and other original data collection (via survey or other methods);

- Curating and preparing datasets of various sizes and formats for research use;

- Producing reports, fact sheets and press releases on timely and relevant topics, often in close collaboration with CIRCLE colleagues;

- Providing feedback, assistance, and support to colleagues at Tisch College and CIRCLE on research-related tasks, as needed;

- Representing CIRCLE at a wide range of events including research conferences;

- Answer queries from reporters about CIRCLE research;

- Performing administrative duties as needed, as they pertain to CIRCLE operations; and

- Participating in activities and meetings that involve Tisch College staff.

2. Quantitative Researcher for NSLVE (the National Study of Learning, Voting, and Engagement)

To join a team of researchers working on the National Study of Learning, Voting, and Engagement (NSLVE) at the Jonathan M. Tisch College of Citizenship and Public Service, Tufts University. NSLVE is a service to colleges and universities nationwide, providing colleges and universities with their students’ voter registration and voting rates, broken down by individual student characteristics (e.g., field of study). Currently, the database consists of nearly 700 colleges and universities and 6.7 million de-identified student records.

Responsibilities:

- Support data analysis of a large national dataset: Calculate tailored campus-level data for participating institutions. Respond to internal data requests for data for presentations and resources

- Resource development: Support the development of the resources and tools for colleges and universities. Support the development of publications, both peer reviewed and self-published, on college student political engagement

PhD candidate preferred; MA candidate will be considered based on quantitative research experience

Mr. Bryant, Take Down the Flag

or "Governor, Take Down This Flag," in The Clarion Ledger, September 20, 2015, 2C.

My piece, “Mr. Bryant, Take Down the Flag,” came out in The Clarion Ledger this morning. In the printed version, the title is “Governor, Take Down this Flag.” For the next week or two, please head to the electronic version of the piece on the newspaper’s site. You can download and print a PDF of the article by clicking on the image of the printed version.

My piece, “Mr. Bryant, Take Down the Flag,” came out in The Clarion Ledger this morning. In the printed version, the title is “Governor, Take Down this Flag.” For the next week or two, please head to the electronic version of the piece on the newspaper’s site. You can download and print a PDF of the article by clicking on the image of the printed version.

I’ll soon post the full article on my site. For now, be sure to check out my blogpost arguing that “Racism Defies the Greatest Commandment.”

Arguments Against Deliberation

I spent much of the day yesterday reading about how deliberation is critical for democracy.

John Dryzek, for example, argues that fundamentally, it is the presence of deliberation which determines whether a state is truly a democracy. “…Democratic legitimacy,” he writes, “resides in the right, ability, and opportunity of those subject to a collective decision to participate in deliberation about the content of that decision.”

But while there seems to be much agreement that deliberation is a nice ideal, it is far from clear that such a theoretical ideal is attainable.

To be fair, most advocates of deliberation don’t argue that it is the only mode of democracy. Whether imperfect or inefficient for some tasks, a democracy must reasonably use other tools as well.

“Certain non-deliberative forms and mechanisms that intrinsically employ coercive power are legitimate and necessary procedures of democracy more broadly conceived,” Jane Mansbridge argued in a 2010 paper, adding that these additional forms are only acceptable “to the degree that they and their procedures emerge from and withstand deliberative, mutually-justificatory, scrutiny.”

But what if deliberation is actually bad for democracy? What if deliberation served to reinforce power dynamics rather than over come them?

That’s essentially the argument Lynn Sanders makes in Against Deliberation.

She begins with a jab at the deliberation community: “To begin, one might be suspicious of the near consensus among democratic theorists on its behalf. It isn’t clear, after all, that this wide endorsement has itself emerged through a genuinely deliberative process: democratic theorists are a select group who cannot and do not claim in any way to represent the perspectives of ordinary citizens.”

In my experience, the deliberative community is largely white – a point that comes up often as proponents of deliberative democracy actively work to address this shortcoming by recruiting speakers of color and seeking to engage diverse groups in conversation.

Deliberation as democracy doesn’t work if only some views are in the room.

But Sanders doesn’t end her critique there. A diverse group of participants may not be enough to ensure the ideal dialogue of deliberation.

“If we assume that deliberation cannot proceed without the realization of mutual respect, and deliberation appears to be proceeding, we may even mistakenly decide that conditions of mutual respect have been achieved by deliberators,” she writes.

I imagine the room where “the boss” asks for feedback and nobody speaks. Where power dynamics have led to a culture of silence and quiescence – so whoever’s in charge can say the right things and do the right things, while all those without power have internalized the unmistakeable subtext: your view doesn’t matter.

John Gaventa compellingly captures this dynamic in Power and Powerlessness: Quiescence and Rebellion in an Appalachian Valley, as he tracks the history of power dynamics in poor Appalachian communities. In democratic elections, people would vote against their interests for “the company man.” They didn’t have to be threatened – they knew what happened to people who didn’t.

“Power relationships, once established, are self-sustaining,” he wrote. That is, a stranger dropped into a situation might see people autonomously choosing to act in a given way, but a historian of local power dynamics would see that there was something much more insidious at work.

Sanders takes a similar line of argument in warning against deliberation:

Even if democratic theorists notice the inequities associated with class and race and gender, and, for example, recommend equalizing income and education to redistribute the resources needed for deliberation – even if everyone can deliberate and learn how to give reasons – some people’s ideas may still count more than others. Insidious prejudice may be unrecognized by those citizens whose views are disregarded as well as by other citizens.

Prejudice and privilege do not emerge in deliberative settings as bad reasons, and they are not countered by good arguments. They are too sneaky, invisible, and pernicious for that reasonable process.

That’s a challenge that hasn’t been sufficiently addressed by deliberation advocates. I think it’s a challenge most advocates are aware of, and no doubt its the sort of concern that keeps them up at night.

To be fair, the problem isn’t just one for deliberation. Given such pernicious prejudice, other democratic tools might find themselves equally unmatched. Deliberation may even be one of the most potent tool in combating that prejudice.

For example, pointing to successful truth and reconciliation activities around the world, Dryzek argues that “deliberation also can play a part in healing division.” Perhaps deliberation, while flawed in a flawed world, is a critical tool to slowly chipping away at those divisions and prejudices. Perhaps deliberation, while ideally requiring equalization, is ultimately a path to equalization itself.

Sanders concerns aren’t a reason to throw out deliberation – merely a reason to be continually, productively critical of how it is realized. Perhaps less than the ideal is still enough.

The question this raises for me is one of measurement. How can you tell the difference between a truly good deliberation and one that merely looks good on paper while masking the deeper quiescence of oppression?

two degrees of Christopher Marlowe

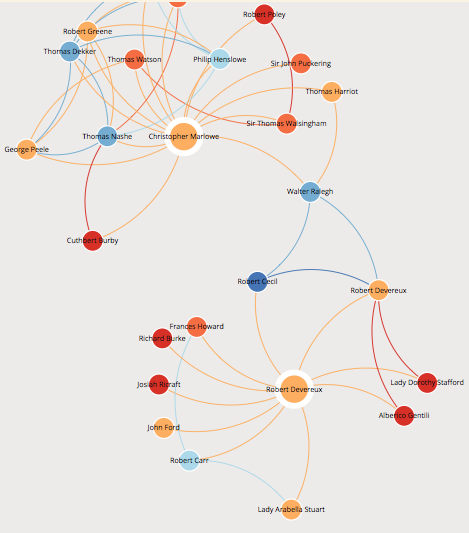

In The Reckoning (1994), Charles Nicholl carefully investigated the 1593 murder of Christopher Marlowe, arguing that it resulted from a struggle between the rival spy networks of Walter Raleigh and Robert Devereux (the 2nd Earl of Essex). It’s a compelling read and a brilliant use of scattered historical records to reveal hidden connections. But The Reckoning predated the current enthusiasm for actually mapping networks and crowd-sourcing the data. Now we have Six Degrees of Francis Bacon, a network map of documented figures from English history, 1500-1700. Using that tool, one can quickly create a map that shows the networks of Christopher Marlowe and Essex, with Raleigh appearing as an intermediary.

The diagram is by no means complete. For instance, Thomas Kyd is in the database but not linked to his former housemate, Marlowe; and the man who probably stabbed Marlowe, Ingram Frizer, isn’t on the map at all. But that isn’t a criticism, for the organizers ask visitors to add data. How many more stories will come to light as the map grows and historians use it?

(See also the murder of Marlowe and my version of “come with me.”)

@Stake: A Role-Playing Card Game

The Engagement Lab at Emerson College created @Stake, a role-playing card game used to foster decision-making, empathy and collaboration. The players take various roles and create questions based on real life issues to deliberate on during the game. All participants pitch their ideas under a time limit and one of the players, “The Decider” will choose who has the best idea and award points.

Development of @Stake:

Planning issues often involve conflicting interests coupled with deep resentments and community divides. Building a new highway, for example, is seldom only a question of the highway’s design, but the destiny of the land, the community, and individual residents.

We were amazed at the success of @Stake in driving productive conversation at our UNDP workshop, and took it back to the Lab for further development. Since then, it’s been used at the Frontiers of Democracy Conference, The Jewish Federation, youth ambassador programs for inner city planning institutions in Boston, and the United Nations in New York. Numerous expansions and customization packs have made the game robust enough to aid in processes of all types nationally and across the world.

Since its inception, @Stake has become one of our best tools for proving to others that games can be productive civic tools.

How to play @Stake:

What is it about? Before the game takes place, the play group must brainstorm topics for the game. The topics selected should be important questions for whatever real world process matters most to the players and their organization (ex. “How can we get young people more involved in local issues?”).

The Decider Once the question for each round has been established, one player becomes the first “Decider,” the player who will pick from the other players’ pitches and determine which is best. It’s up to them to keep time, promote fair play, and make prompt decisions in awarding points.

Role Cards All other players are assigned roles such as Mayor, Activist, or Student. Each role card features a short bio and three agenda goals that the players try to include in their pitches for bonus points.

The Pitch Players hear the question for the round, and are then given one minute to devise an idea. Pitching occurs in two phases. Each player has one minute to give their initial pitch to the Decider, and then there is a short discussion period during which players may ask questions of one another and try to achieve compromises to attach their agenda items to others’ plans.

Decider At the end of the round, the Decider must pick a winning pitch. That winning player earns points, then every player earns bonus points based on their agenda items. The new decider is the player that won the previous round.

**When playing @Stake, please tweet or use the hashtag #AtStakeGame to share your gameplay moments.

About The Engagement Lab

The Engagement Lab is an applied research lab at Emerson College focusing on the development and study of games, technology, and new media to enhance civic life. The Lab works directly with its partner communities to design and facilitate civic engagement processes, augment stakeholder deliberation, and broaden the diversity of participants in local decision-making. Along with the Salzburg Academy on Media and Global Change, the Engagement Lab serves as the hub of a global network of engagement and new media organizations.

Follow on Twitter: @EngageLab

Resource Link: http://elab.emerson.edu/games/@stake/

Critical Elements of Deliberation

Many democratic theorists take deliberation to be a critical piece of democracy.

Indeed, in his 1989 piece Deliberation and Democratic Legitimacy, Joshua Cohen builds off Rawls to define “public deliberation” in the very context of democracy:

When properly conducted, then, democratic politics involves public deliberation focused on the common good, requires some form of manifest equality among citizens, and shapes the identity and interests of citizens in ways that contribute to the formation of a public conception of the common good.

Echoing this sentiment, Centenary Professor at the Centre for Deliberative Democracy and Global Governance John Dryzek argues that “the more authentic, inclusive, and consequential political deliberation is, the more democratic a political system is.”

But what exactly is public or political deliberation?

Cohen writes that “the aim of ideal deliberation is to secure agreement among all who are committed to free deliberation among equals.” That is, deliberation is more than just compromise:

Deliberation, then, focuses on debate on the common good. And the relevant conceptions of the common good are not comprised simply of interests and preferences that are antecedent to deliberation. Instead, the interests, aims and ideals that comprise the common good are those that survive deliberation, making claims on social resources.

People may enter deliberation with their own self-interest in mind, but through the process of deliberation they will reflect on their own interests, listen genuinely to the interests of others, and collective come to recognize the common good.

This process of reflecting on your own self-interest may be critical to democracy: Dryzek goes so far as to argue that “political systems are deliberatively undemocratic to the extent that they minimize opportunities for individuals to reflect freely on their political preferences.”

A 2010 paper by Jane Mansbridge with an all-star list of co-authors James Bohman, Simone Chambers, David Estlund, Andreas Føllesdal, Archon Fung, Cristina Lafont, Bernard Manin and José luis Martí actively accepts the reality of self-interest and conflicts of interest, and seeks to update the “classic model” of the deliberative ideal to incorporate these realities.