Friends, hope this post finds you well on this Election Eve! We have been working hard on improving our resources. In addition to our Civics in Real Life tool, we of course have Civics360. That latter platform has entered a beta stage for relaunch, and I wanted to take a few minutes and show some of the changes coming to Civics360.

The most significant change is to the registration process. Traditionally, teachers and students would register individually, and we asked for emails, names, and all that fun and potentially privacy-problematic stuff. Well, recognizing this, we have moved forward with updating the system to much easier and whole new process.

Teacher Registration

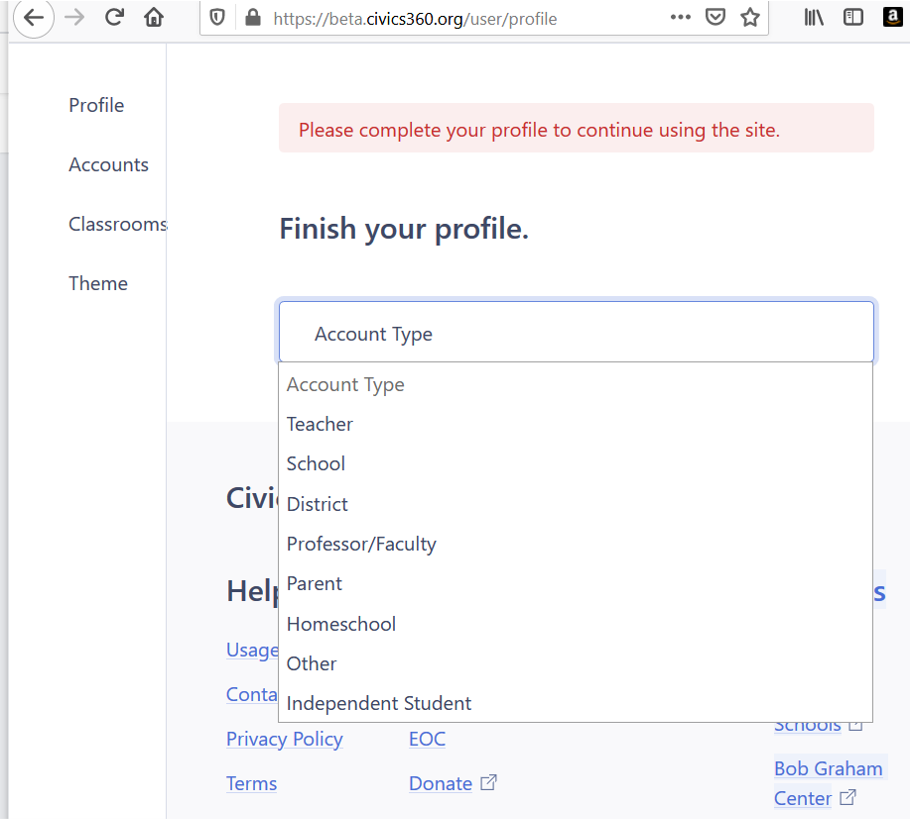

When you access Civics360, you’ll be asked to select an account type. As an educator, you would select that option.

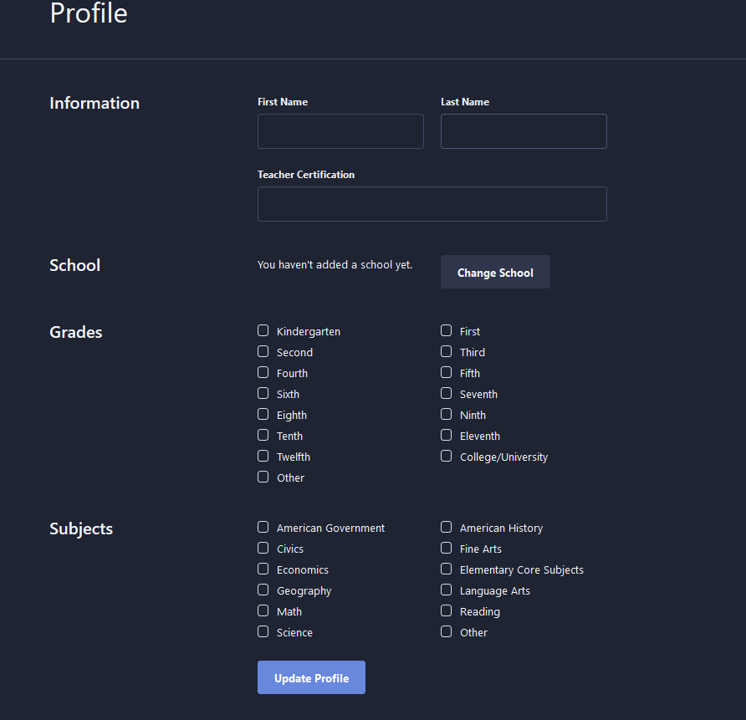

Once you have selected that, enter your the email and password you want to use. You’ll be asked to create a profile.

Enter your information. A new change that should benefit folks not working in a Florida public school: you can now enter your own school!

Once you have completed your initial profile, you will be taken to your own page. Here, finish your profile with some more specifics.

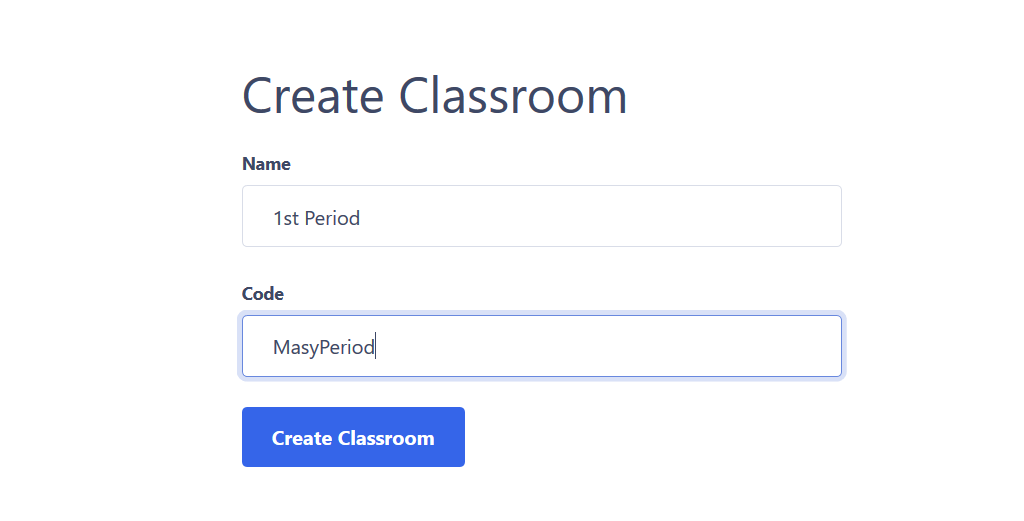

Now, a brand new feature that we are adding: classrooms! You will be able to create your own ‘class’.

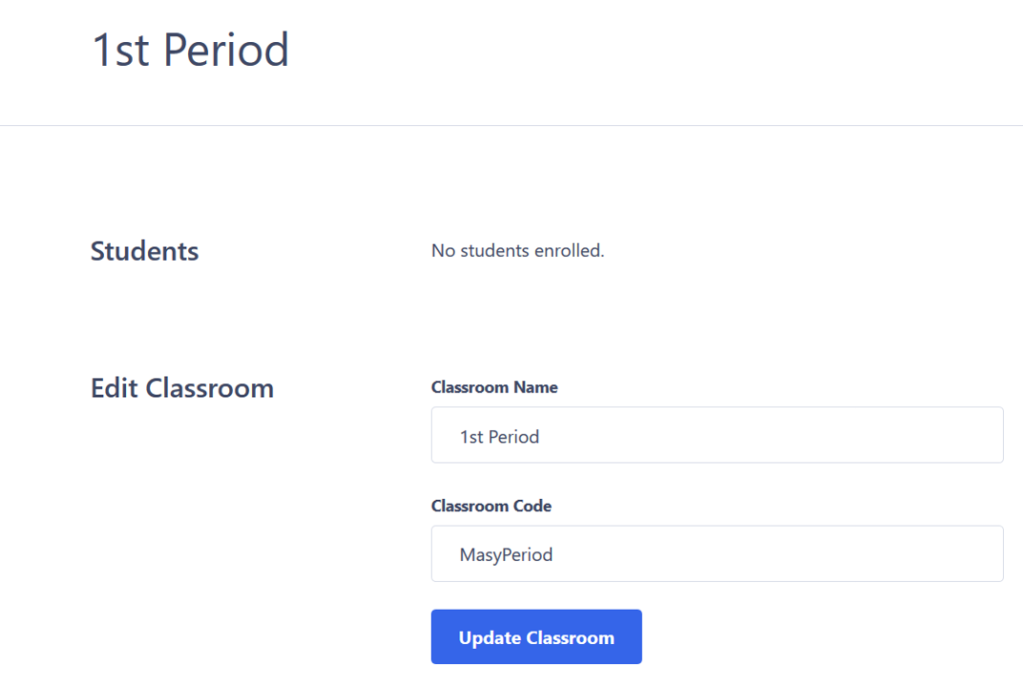

Note the code that was created for that class. That’s important! Right now, I have no one enrolled, as you will see below.

I guess I need some students! So I will send them to Civics360, armed with the classroom code I created.

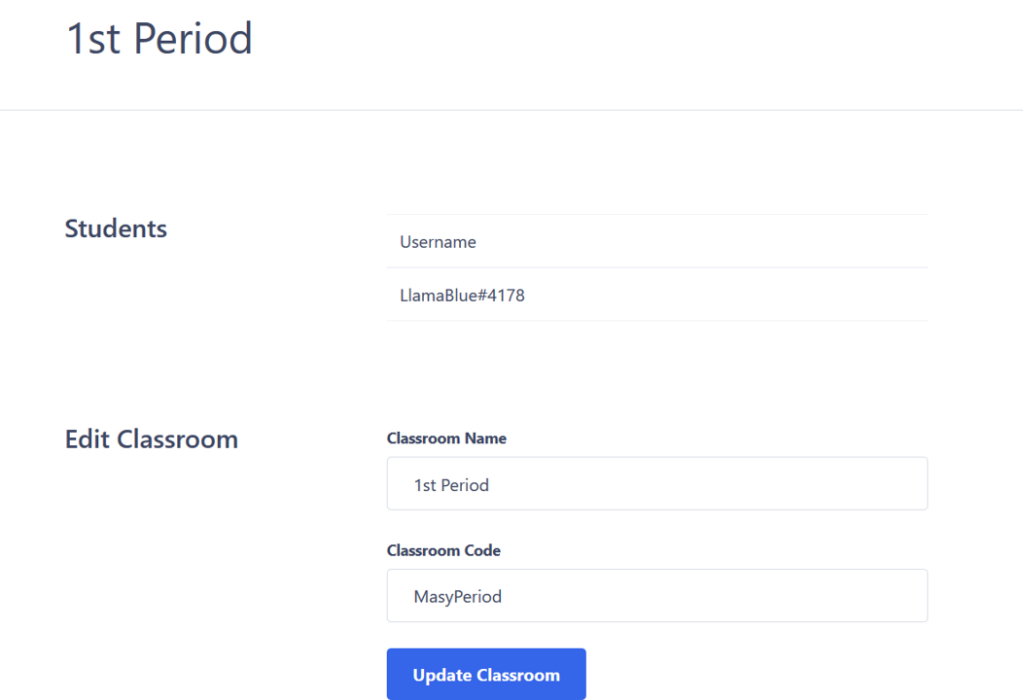

The entire registration process for students has changed significantly! Now, they will get a randomly generated user name, and can create their own password. They should also enter the classroom code you created! You’ll note that it auto-identifies what the class is. So let’s pop back over to the teacher profile!

And I have the first student in my class! With this new approach, the goal is to let you handle registration and password recovery yourself, immediately, as well as tracking student work and having separate class groups.

Now, THIS IS ALL STILL IN THE BETA TESTING PHASE and we are working hard to ensure it is bug free and does everything we need it to do. I do not yet have an estimated launch time, but we are excited to at least give you a preview! The most important change is to the student registration process. We will no longer ask them for ANY information, to better address privacy concerns, and it is now essentially a one click registration for students!

I hope that this preview of what is to come was interesting, and that you will continue to use Civics360 and the other resources that we offer. Questions? Shoot us an email anytime!

Silke and I are excited about deepening the conversation about the commons in Spain and Latin America with a Spanish translation of

Silke and I are excited about deepening the conversation about the commons in Spain and Latin America with a Spanish translation of