Engaging Ideas – 12/23

Open New York

Case: Open New York

Help NCDD Rise to the D&D Challenges of 2017

As 2016 comes to a close, our NCDD team has been looking back proudly at what we’ve accomplished this year, but also reflecting soberly on the challenges that 2017 will bring for the nation and the dialogue & deliberation field. And as we reflect on our next year, we know one thing is for sure: we will need your help.

NCDD is here to support our members and the broader network of people and organizations working to help people come together across divides and make better decisions for our communities. All of the work we do is for the benefit of the field – connecting members to one another at our gatherings, introducing new technology and spotlighting key projects, engaging in conversations about the challenges we face and exploring new opportunities, collaborating with members on resources and research, sharing the latest news on our blog, and curating tools and resources in the Resource Center.

NCDD is here to support our members and the broader network of people and organizations working to help people come together across divides and make better decisions for our communities. All of the work we do is for the benefit of the field – connecting members to one another at our gatherings, introducing new technology and spotlighting key projects, engaging in conversations about the challenges we face and exploring new opportunities, collaborating with members on resources and research, sharing the latest news on our blog, and curating tools and resources in the Resource Center.

But many people aren’t aware that NCDD is an organization of just 5 core staff, and that though we work passionately to support the vital work of the D&D field, our financial situation dictates that all of us only work part time. Many people also don’t realize that a major source of NCDD’s funding comes in the form of the dues paid by our incredible members. We’ve been able to secure some grant money in the past, but part of next year’s challenge is that some of the grants we’ve relied on will run out. At the same time, the work of our field will be more important than ever in 2017.

That’s why we are inviting our network to renew your commitment to strengthening the field in the coming year by renewing or upgrading your membership, joining NCDD as a member, or making a donation today! NCDD is only as strong as our members’ and our community’s support, and in these lean times for small non-profits like us, your contributions are what will keep our critical work afloat. Member dues and donations go directly to supporting NCDD’s programming and staff, and we invite you to make us part of your end-of-the-year giving today!

But more than just keeping our work afloat, NCDD will be taking on several new initiatives in 2017 to further support the network and advance the field:

- We will be continuing to steward the Conversation Café process and support its network of practitioners

- We will be scaling up our Emerging Leaders Initiative to cultivate and grow the capacity of our field’s next generation of leadership

- We will be partnering with libraries all over the country to strengthen their ability to be spaces for convening dialogue and deliberation that serves their communities

- We will continue to lift up resources and initiatives that are helping the country in Bridging Our Divides and finding ways to move forward together

Adding these exciting initiatives to NCDD’s regular work in the new year will be a challenge for our team, but we are committed to rising to those challenges, and we know we can do it if our members are behind us. So as 2016 winds down, please commit to supporting us as we support you and the important work that our field is doing by becoming a member, renewing/upgrading your membership, or making a donation today!

We know that 2017 will be a year where dialogue & deliberation are more essential than ever and that it can make a key difference in the direction of our communities and our country. We are so honored and grateful to serve such an amazing network, and NCDD is determined to expand the reach and impact of our individual and collective work in 2017. We ask that you support us in our continued efforts to do so.

We know that 2017 will be a year where dialogue & deliberation are more essential than ever and that it can make a key difference in the direction of our communities and our country. We are so honored and grateful to serve such an amazing network, and NCDD is determined to expand the reach and impact of our individual and collective work in 2017. We ask that you support us in our continued efforts to do so.

Looking ahead with hope,

The NCDD Team

2016 Best List

Let those with enough time to consume all the media in a field decide on the objective bests-of-2016. What follows is a completely subjective list of bests, idiosyncratically limited by what I’ve actually had time to watch, read, or listen to:

Best New Book in Philosophy:

We don’t think hard enough about the metaphysics that underwrites the social sciences. Epstein is more reductionist than he lets on, but this was the book that had me thinking hardest this year.

Runner-up: Nussbaum’s Anger and Forgiveness. It’s pretty great, but I think it loses steam in the speculative last section.

Best New Book in Political Science:

What if democratic theory is a bit too idealistic? The next issue of The Good Society will have a review by Celia Paris.

Runner-up: Katherine Cramer’s The Politics of Resentment.

Best Article:

“The Unnecessariat,” by anonymous blogger More Crows Than Eagles helped me formulate some things I’ve been trying to say about superfluousness for a while. I think it was the first time a lot of urban liberals in my circles sat down to think hard about non-college-educated whites.

Runners-up: “The Strange Case of Anna Stubblefield” and “My Four Months as a Private Prison Guard.”

Best Post (here at anotherpanacea.com):

“Arendt’s Metaphysical Deflation” hit the front page of the philosophy subreddit briefly, which was weird.

Ironically, large parts of that article are drawn from my dissertation, so I guess I do deserve this Ph.D.!

Runner-up: “Imperialism as a Response to Surpluses and Superfluousness,” where I start to work out the Arendtian critique of finance capitalism.

Best television series:

Fully-realized far-future worlds, with fascinating characters and an interesting set of mysteries.

Runners-up include The Good Place, Luke Cage, and The Magicians.

Best Movie:

No Award Given:

I didn’t read a sin

So what did I miss?

Six Hundred Years of Participatory Democracy: The Case of the Oromo Gadaa Political System in Ethiopia

Epson printer customer care number UK

Most Popular Posts from 2016

“That man who has nothing to lose:” Black Americans and Superfluousness

Long before white Americans felt like their society had abandoned them, Black Americans knew the feeling. Just like whites do today, some Black Americans responded to earlier superfluousness by “clinging to guns and religion” to use Barack Obama’s famous analysis. (cf. Kinsley gaffe) Here’s James Baldwin, describing the Nation of Islam:

“I’ve come,” said Elijah, “to give you something which can never be taken away from you.” How solemn the table became then, and how great a light rose in the dark faces! This is the message that has spread through streets and tenements and prisons, through the narcotics wards, and past the filth and sadism of mental hospitals to a people from whom everything has been taken away, including, most crucially, their sense of their own worth. People cannot live without this sense; they will do anything whatever to regain it. This is why the most dangerous creation of any society is that man who has nothing to lose. You do not need ten such men—one will do. And Elijah, I should imagine, has had nothing to lose since the day he saw his father’s blood rush out—rush down, and splash, so the legend has it, down through the leaves of a tree, on him. But neither did the other men around the table have anything to lose. –James Baldwin, “Down At The Cross: Letter from a Region in my Mind“

Baldwin was no fan of Elijah Muhammed’s movement, but he tries to understand it and he seems to sympathize. And what he calls out in these lines is an overriding sense of loss–one that can justify any effort or sacrifice to overcome. That loss of worth, which Baldwin wants to depict as something much deeper than “self-esteem,” is tied not to airy questions of recognition but to material harms and embodied injuries: frisks and kicks by “legitimate” authority that go unanswered, murdered fathers that go unmourned by white society.

Baldwin even interprets the turn to Islam as a turn away from Christianity’s whiteness–from the forgiveness that it seems constantly to demand from white supremacy’s victims.

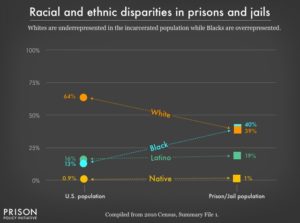

Today I know more Black Muslims than Arab ones, but mostly they’re imprisoned. And that, too, is a form of superfluousness: of the 2.3 million people incarcerated in the US, 40% are Black, even though Blacks make up only 13% of the population.

It’s hard not to see imprisonment of African-Americans as primarily a reaction to their enforced superfluousness. Labor market prejudices create a circumstance where unemployment rates for African-Americans are roughly double the rates for whites, at every education level. My students believe (and I agree) that the War on Drugs is largely a war on Black participation in the black labor market. (Recall the Ice Cream truck war of the summer which helps explain how police and the courts can make black markets less or more violent.) It’s an attempt to foreclose available forums for Black entrepreneurship. It’s notable that as marijuana legalization proceeds state-by-state it begins in white places, and the new profits and businesses are primarily white-owned.

To be rendered superfluous is a particularly odd phenomenon, and at least in the formulation I’ve lately been thinking about, it seems uniquely tied to relative deprivations of status and respect. I want to believe that respect and recognition matter less than life or health. We all have things we could lose, and honor is the least of these.

But that’s simply not how people act. Flourishing matters to most people more than survival, and flourishing requires a community of esteem. It requires reputation and character assessments, it requires that the agents of the state give you equal protection and don’t target you as a unique threat.

Some parts of Black America responded to superfluousness by clinging to god and guns, but for the most part African-Americans responded by becoming the center of cultural attention. There’s little argument that Black culture simply is American culture at this point, as almost all of our distinctively American institutions and cultural traditions are shot-through with Blackness even if it is unacknowledged. Baldwin charged that even myths of Black laziness or violence serve an important function in White America: they are our “fixed star” and moving out of their place of subordination would shake our “heaven and earth… to their foundations.”

Yet whites don’t seem to be willing to create their own economies of esteem in this way. Something–perhaps supremacy itself–has rendered them too lazy, too dependent on long-lost tradition and long-gone cultural victories. Consider Katherine Cramer’s formulation: rural Wisconsinites resent that the urban centers have deprived them of “power, money, and respect.” But they’re simply wrong: they’ve seen no real deprivations of power or money compared to Black Americans. It’s certainly true that they receive less respect than they used to get, less deference and less cultural attention. But this is a downfall from absolute supremacy and literal enslavement–enforced by rule of law. We have a long way to go before we aren’t still reaping what WEB Du Bois called “psychic wages” of white supremacy. (I prefer to call them psychic dividends, since it’s important that they are not a reward for work, but rather like a racial trust fund.)

How much should that matter? In my heart, I want to believe that people with a surplus of money, power, and respect should share. And I want to believe that it’s not a finite resource, that more souls can and will produce more of each if they’re not forced into superflousness. I think of Malcolm X, whose industriousness and self-invention could not be halted or stultified by racism or even Elijah Muhammed’s theocratic nonsense, only assassinated. But that’s where my analysis is probably wrong: when people have the money and power, they’re well-placed to demand the respect or punish its absence.

Robert Macfarlane: How Language Reconnects Us with Place

I have come to realize that language is an indispensable portal into the deeper mysteries of the commons. The words we use – to name aspects of nature, to evoke feelings associated with each other and shared wealth, to express ourselves in sly, subtle or playful ways – our words themselves are bridges to the natural world. They mysteriously makes it more real or at least more socially legible.

What a gift that British nature writer Robert Macfarlane has given us in his book Landmarks! The book is a series of essays about how words and literature help us to relate to our local landscapes and to the human condition. The book is also a glossary of scores of unusual words from various regions, occupations and poets, showing how language brings us into more intimate relations with nature. Macfarlane introduces us to entire collections of words for highly precise aspects of coastal land, mountain terrain, marshes, edgelands, water, “northlands,” and many other landscapes.

In the Shetlands, for example, skalva is a word for “clinging snow falling in large damp flakes.” In Dorset, an icicle is often called a clinkerbell. Hikers often call a jumble of boulders requiring careful negotiation a choke. In Yorkshire, a gaping fissure or abyss is called a jaw-hole. In Ireland, a party of men, usually neighboring farmers, helping each other out during harvests, is known as a boon. The poet Gerard Manley Hopkins called a profusion of hedge blossom in full spring a May-mess.

You get the idea. There are thousands of such terms in circulation in the world, each testifying to a special type of human attention and relationship to the land. There are words for types of moving water and rock ledges, words for certain tree branches and roots, words for wild game that hunters pursue. There are even specialized words for water that collects in one’s shoe – lodan, in Gaelic – and for a hill that terminates a range – strone, in Scotland.

Such vocabularies bring to life our relationship with the outside world. They point to its buzzing aliveness. There is a reason that government bureaucracies that “manage” land as "resources" don’t use these types of words. Their priority is an institutional mastery of nature, not a human conversation or connection with it.