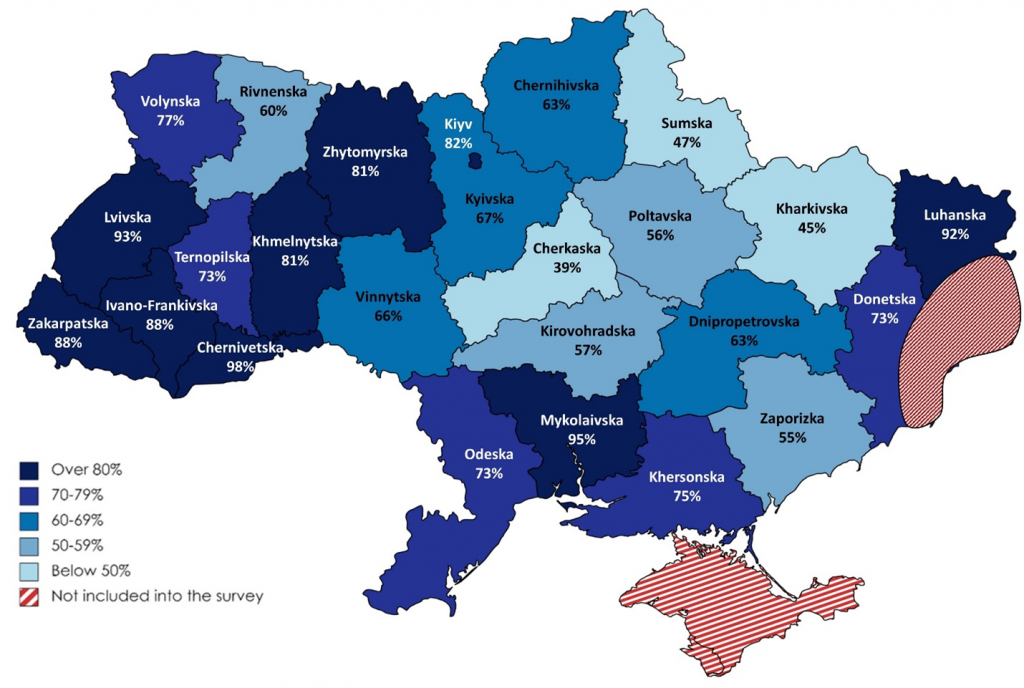

Pippa Norris and Kseniya Kizlova have crunched some numbers from the European Social Survey’s Ukraine sample (2,901 people) to investigate “what mobilises the Ukrainian resistance?“

In autumn 2020, Europeans were asked: “Of course, we all hope that there will not be another war, but if it were to come to that, would you be willing to fight for your country?” About 70% of Ukrainians said yes.

That number isn’t especially meaningful on its own, since it is hypothetical. However, the correlates of the responses are interesting. As the table from Norris and Kizlova shows, Ukrainians were more likely to say they would fight if they felt patriotic, if they spoke Ukrainian rather than Russian at home, if they were confident in their government, and if they supported democratic values. Those are outputs of a statistical model, so they imply that each of these factors matters by itself. For instance, democratic values correlate with a willingness to fight when holding patriotism/nationalism constant. Also note that although speaking Ukrainian was a correlate of willingness to fight, 51% of those who spoke Russian at home said yes.

Since this was a question about personally taking up arms, it is not surprising that being male and younger correlated with positive responses. In general, the literature on nonviolent resistance suggests that it mobilizes people who are not young men.

Norris & Kizlova find regional differences, but not in a simple way. Indeed, the highest rate of willingness to fight was immediately adjacent to the Russian proxy “republics” in the east, followed by the Lviv area far to the west.

See also: civilian resistance in Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus; when a university is committed to democracy (about the Ukrainian Catholic University in Lviv); and why I stand with Ukraine (from 2015)