I’m speaking briefly tomorrow at a Tufts Institute for Innovation symposium on “Research, Innovation, and Community Engagement.” I may say something along these lines:

It is exciting and valuable to put these four words together. We need innovation because existing strategies have not solved stubborn problems. We need research to explain the problems and to assess what works. We need communities, meaning not just populations of people who happen to live in particular places, but groups of people who have networks and norms that allow them to improve the world. (Voluminous scholarship finds that community ties are essential for success.) And we need engagement if we want research and innovation to influence the world.

So I am a fan. But I would like to take a few minutes to note some risks that may arise if we try to combine research, innovation, community, and engagement in the wrong ways.

Research and innovation go together neatly. In fact, university-based research must be innovative, almost by definition. An inquiry doesn’t count as “research” if it has been done before. To be sure, some academic research is highly routine and standard. But that kind of work is valued less than original research. Innovation is esteemed in the university. Famous scholars are innovators.

Innovation is also valued highly in the private sector, in part because making or doing something new can be especially profitable. One definition of a “commodity” is a good for which the demand is met by undifferentiated suppliers. It doesn’t matter whether your shirt was stitched by Bangladeshi workers or a machine in Germany; the shirt comes out the same. A commodity yields low profits because anyone can turn capital into the good and compete. Innovation allows the innovator to reap greater advantage by avoiding competition.

Since innovation is prized in the academy (where the currency is fame) and in the marketpace (where the currency is money)–and since the academy and the market are merging–it is no surprise that glamor attaches to the idea of innovative research that produces innovative solutions that go to market. That is the current ideal.

It is an ideal that also finds its way into public policy. The Obama Administration loves concrete new policy interventions that can be rigorously evaluated. In 2o13, for instance, the administration proposed $200 million in a competitive pool for state governments that cut energy use and expanded HOPE (Hawaii’s Opportunity Probation and Enforcement scheme), which had performed well in evaluations. But it proposed to cut Social Security by $130 billion and Medicare by $380 billion.

Social Security and Medicare are old, not innovative. These big, old programs are not subject to being invented and then tested in randomized experiments. Yet cutting $130 billion from a basic entitlement is massively more consequential than spending $200 million on innovations. And the reason for the cuts was not an actual preference by the administration; it was a function of the balance of power, with Republicans controlling Congress. If we presume that innovation by itself solves problems, we forget about power–power to devise innovations, power to use them, and power to change larger systems that have little to do with innovation.

If innovation and research fit comfortably enough together, innovation and community make a more difficult pair. Communities do not necessarily need innovation. They may prefer to preserve what they have, or to develop in regular and predictable ways. They may value tradition. They will ask whether an innovation is an improvement or a new evil. For these and other reasons, they often resist innovations.

Even when it comes to research, communities may not need originality. Once it is known that cigarettes cause cancer, a community needs to know who is smoking and where the cigarettes come from. The original discovery about the impact of tobacco was valuable, but now the community just needs routine data of the kind that will not look impressive on an academic’s CV.

In a competitive research university, the more innovation, the better. In a community, that is not the case. True, a world of innovation can be exciting and liberating. But if everyone else is innovating, it becomes difficult to make plans for yourself. That actually undermines personal liberty; you are constantly reacting and adjusting to other people’s innovations. The same is true for communities. They cannot govern themselves and form durable laws if everything if always being changed. As James Madison argued: A “mutable policy … poisons the blessings of liberty itself. It will be of little avail to the people, that the laws are made by men of their own choice, if the laws … be repealed or revised before they are promulg[at]ed, or undergo such incessant changes, that no man who knows what the law is to-day, can guess what it will be to-morrow.”

I haven’t said anything about “engagement” yet. Real engagement is not a one-way flow. For instance, to develop and deploy an innovation in a community does not reflect engagement. Two people are said to be engaged if they plan to form a couple. Two gears are engaged if turning either one moves the other. Two gears are engaged if stopping one stops the other. A community and a university are engaged if they form a kind of couple, and if motion–or stillness–on either side influences the partner.

Communities can innovate. And civic engagement can be done in innovative ways. Indeed, Carmen Sirianni and Lewis Friedland’s book, Civic Innovation in America: Community Empowerment, Public Policy, and the Movement for Civic Renewal is an indispensable work that counters narratives of civic decline by showing that new forms of civic engagement have been painstakingly developed to respond to a changing world.

In an age of innovation, we’d better engage citizens in new ways. In that respect, innovation and engagement fit neatly together. But we must not yield to the assumption that “innovation” is desirable because it is the path to fame and profit. If we are really engaged with communities, they will have the power to stop or alter the cleverest innovations. At least some of the power will come from their side.

In short, I am all for developing innovative solutions to social problems and engaging communities in using them. But we must not forget issues of power and of ethics. Some innovations are good, some are bad, and some are insignificant compared to bigger social decisions. A relationship should form between any academic or entrepreneur who is strongly motivated to innovate and the community that might want to participate. That relationship must be ethical and fairly equitable. Ideally, some of the insights and innovations will come from the community side. And like an engaged gear, the community will have the power to stop and prevent the research partner from moving forward.

The post Innovation and Civic Engagement appeared first on Peter Levine.

on-Cogs’ and ‘Soft Skills.'”

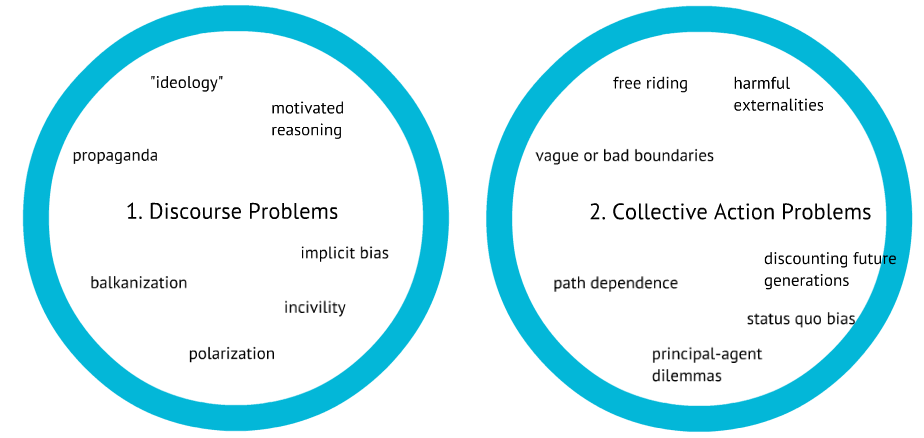

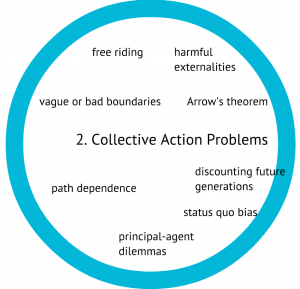

on-Cogs’ and ‘Soft Skills.'” Academics certainly study these problems. Google Scholar finds more than 77,000 books or articles on free-riding, which is one variety of a collective action problem. It finds more than 9,000 citations of implicit bias, which I would categorize as a discourse problem. There is no shortage of material to read, and much of it is useful.

Academics certainly study these problems. Google Scholar finds more than 77,000 books or articles on free-riding, which is one variety of a collective action problem. It finds more than 9,000 citations of implicit bias, which I would categorize as a discourse problem. There is no shortage of material to read, and much of it is useful. limitations that we should address:

limitations that we should address: