Schools and colleges, daily newspapers and broadcast television channels, and certain civic associations are prone to present themselves as neutral about politics. They say that they provide information, spaces for discussion, and opportunities to learn skills. Their students, readers, or citizen-members are free to form their own opinions.

Activists in social movements observe that these organizations are not truly neutral (but rather full of implicit values) and argue that grave current injustices require all organizations to take explicit stands.

In response, at least some of the ostensibly neutral organizations declare that they are actually against specific injustices and committed to a better society. Nowadays, they often name their positive objective as “social justice” (a phrase whose deepest historical roots are in Catholic thought). In past decades, they might have talked instead about democracy or freedom.

But although some things are obviously unjust, reasonable people disagree profoundly about what constitutes a positive vision of social justice, and why. Thus–I contend–virtually all of the valuable debate that occurred under the aegis of self-described neutral organizations recurs within organizations that declare themselves for “social justice” without providing a detailed definition of that phrase.

The return of debate is not in itself a bad thing; politics is about persistent disagreement, which responsible citizens can embrace and even enjoy. But it is somewhat naive to expect that a commitment to a vague ideal of social justice will bring consensus. And it is a shame if that expectation leads to disillusionment.

In our current time, this is the main pattern I observe: educational, journalistic, and civic associations strongly proclaim neutrality in response to what appears an uncivil and polarized political debate, and then activists demand that they take a stand in response (mainly) to climate change or domestic US racism. Those are matters of grave concern and they have generated social movements that are particularly effective at influencing schools and colleges, the media, and local associations (much more so than governments or corporations). In decades past, opposition to US foreign policy and war played similar roles in challenges to neutrality.

But if there is any doubt that people can be committed to something called “social justice,” abhor the same specific injustices, and yet disagree about the very definition of “justice,” consider the current debates between #BlackLivesMatter and Sen. Sanders, #BlackLivesMatter and Secretary Clinton, or Clinton and Sanders.

Those three people/movements place themselves on the left, but the debate about social justice is certainly broader than that, even if the phrase currently has leftish resonances. In an interview with Eric Liu for a project that Eric and I conducted together, Mark Meckler, who had founded Tea Party Patriots, called the police presence in Ferguson “outrageous.” He acknowledged the salience of racism but mainly viewed police violence as an example of a government depriving individuals of liberty. “The state has a lot of power and only recently it is outwardly manifesting that power in costumes and equipment that demonstrate military might. … That is not of society, by and for society; that is against society.” A democratic socialist might agree with much of that and yet read Ferguson more as a story of disinvestment in industrial cities and the failure of our economy to value workers. I’ve quoted Julius Jones of #BlackLivesMatter as a proponent of a third view: that anti-Black racism is a fundamental chord in American history. Note that all of these positions could simultaneously be true, yet the proponents must disagree about solutions. More government? Less government? Remedies targeted at race? At class? Any of those could constitute “social justice.”

To have a theory of justice, you need principles and a way of ranking or adjudicating among them. Maybe equality is one of your principles, but equality of what? (Opportunity, status, power, welfare?) Equality for whom? (All the students who are already in your classroom or at your college? All major demographic groups within America? All American individuals? All human beings?)

And even if equality–defined in a particular way–is a very high principle for you, what about freedom (which comes in at least six different and incompatible forms), sustainability, security, creativity, innovation, community, rule of law, tradition, diversity, prosperity, and efficiency? A reasonable view of social justice is surely an amalgam of many of these principles, reflecting tradeoffs and rankings. We develop such views in part by reflecting on what is bad about the status quo and what we have learned about practical solutions that work. (For instance, we wouldn’t advocate equality of education if we thought that schools were a waste of time.) Thus a theory of justice typically rests on a narrative about the failures and the successes of our society so far. All of that–the narrative, the assessment of actual institutions, the abstract principles, and their ranking–is contestable.

An organization can claim that it is thoroughly neutral, just a platform for its members to debate what is right. Or it can assert that it is for social justice, and then its members will debate what is right. The difference matters–a bit. A claim of perfect neutrality is inevitably false and distracting. A commitment to social justice can usefully raise the question, “What is justice?”

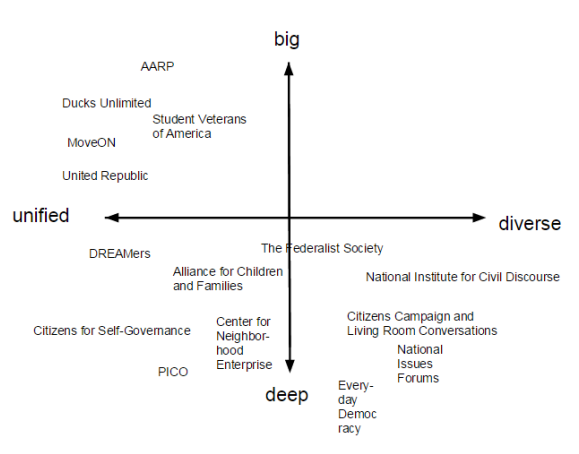

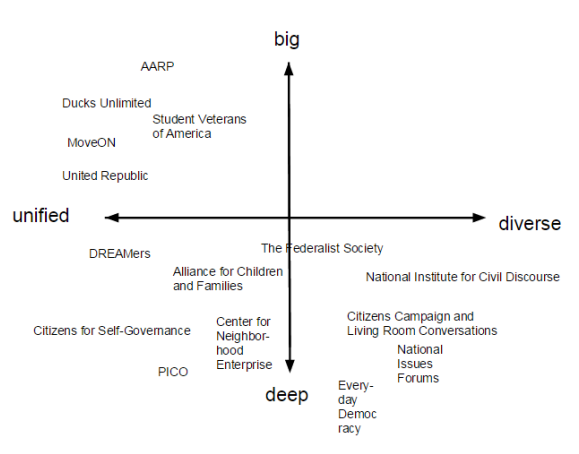

The choice remains how specifically to define the content of social justice. Organizations face choices between ideological diversity and unity and between scale (attracting lots of people) and depth (intensively relating to their members). The more precisely an organization defines its objective, the less hospitable it is to diversity but the more it can achieve unity and advance an agenda. The smaller it is, the better it can work through disagreements, but the bigger it is, the more influence it can have.

I think that organizations that strive to be ideologically diverse and also relatively big are relatively weak and scarce today. Universities and schools and large civic associations can fill that quadrant. It won’t hurt for them to declare themselves for “social justice,” but they would be wise to invite a genuinely diverse debate about what social justice is.