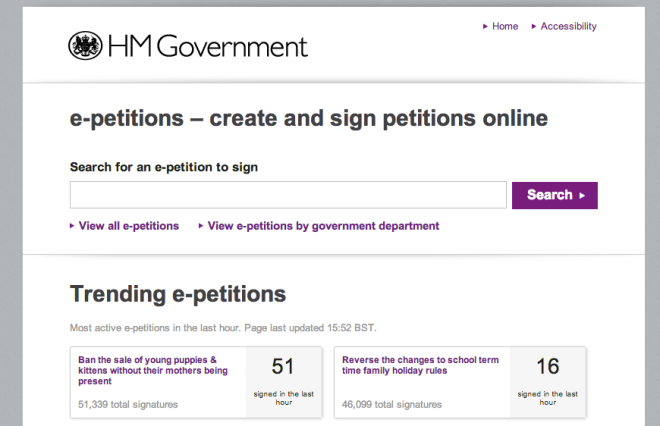

Tom Steinberg recently brought up one of the most important issues for those working at the intersection of technology and governance. It refers to the deficit/surplus of words to describe the “field” (I call it field in the absence of a better word) :

(…) what primary movement or sector is mySociety part of? Or Avaaz? Or Kiva? Or Wikileaks? When I ask myself these questions, no obvious words or names race quickly or clearly to mind. There is a gap – or at best quite a bit of fuzziness – where the labels should go.

This lack of good labels should surprise us because these groups definitely have aims and goals, normally explicit. Also, it is unusual because social and political movements tend to be quite good at developing names and sticking to them.

I personally have witnessed the creation of a number of names, including e-democracy, e-participation, e-governance, government 2.0, and open government. While some may argue that these names are different among themselves, no real consensus exists about what differentiates them. The common denominator is some fuzzy notion that technology may promote more democratic and/or efficient forms of government.

But why the absence of stable terms and the profusion of neologisms? And what are the implications?

The appeal to novelty (argumentum ad novitatem), which asserts that something is superior because of its newness, seems to be one of the reasons behind the constant reinvention of terms. Indeed, adhering to such a logical fallacy might be particularly tempting for the technology community, where new solutions tend to be an improvement over older ones. On top of that, some technological millennialism does not hurt. After all, a constant of humankind is our inclination to think we are living unique moments. Coming up with new names partially fulfils our natural desire to belong to a special moment in history.

But coming up with new terms also allows for “semantic plasticity”, which enables those who use the terms to expand and contract their meanings according to their needs. Take the example of the term “open government data” and its ambiguous meanings: sometimes it is about accountability, sometimes it is about service delivery, other times it is both. Such ambiguity, some might claim, is opportunistic. It creates a larger consumer base that does not only include governments interested in openness as a democratic good, but also less democratically inclined governments who may enjoy the label of “openness” by publishing data that have little to do with accountability. Malleable terms attract larger audiences.

Moreover, new terms (or assigning new meanings to existing ones) also provides additional market entry-points. While it may take 10,000 hours of deliberate practice to become an expert at something, it only takes a few tweets to qualify as a new Gov 2.0 “guru”, an open government “thinker”.

But Tom Steinberg hits the nail on the head when describing why the profusion of names and their terminological inconsistency is problematic:

And this worries me because consistent names help causes to persist over time. If the field of AIDS research had been renamed every 6 months, could it have lasted as it did? Flighty, narrowly used language confuses supporters, prevents focus and is generally the enemy of long term success.

Indeed, the lack of terminological consistency in the field is a major obstacle to cumulative learning. And worse, this problem goes beyond the name for “the field” as a whole, also affecting practices that are part of that very field.

As an illustration, recently some people from the development/opengov worlds have started to unrestrainedly employ the term “feedback loop”. While the understanding around the term (in its latest usage) is imprecise, it normally alludes to an idea of citizen engagement followed by some kind of responsiveness. If there is a reason for the use of the term “feedback loop” in the context of citizen engagement, no serious effort has been made to explain what it is. A term is thus assigned a new meaning to describe things that have been largely studied by others under different names.

I myself haven’t resisted and have used the term a couple of times, but this is not free from implications. For instance, Nathaniel Heller, is a prominent and astute voice in the international Open Government space. Recently, Nathaniel wrote a blog post asking “Is There a Case Against Citizen Feedback Loops”. To date, his post goes unanswered. But had he asked for instance about “the case against (or for) citizen engagement”, I believe a productive conversation could have ensued, based on a couple of thousands of years of knowledge on the matter. But the language defines the audience, and the use of terms like feedback loops reduces the odds of engaging in a conversation with those who hold relevant expertise.

The major problem with this semantic extravaganza relates to the extent to which it blocks the connection with existing knowledge. As new terms come up, the “field” starts, again, to be considered as a new one. And the fact that the majority is unaware of evidence that may exist under other terminology leads to a collective illusion that the evidence does not exist. Then, the “we know very little” sentence starts to be repeated ad nauseam, opening the floodgates to all kinds of half-baked hypotheses (usually masked as “theory of change”) and unbridled calls for “evidence”.

Questions that have been asked in the past, and that have been answered either entirely or partially, re-emerge as if they were new ones. The process of answering these new questions starts again from zero. With neologisms, so dear to those working in “the field”, comes what they claim to despise the most: the re-invention of the wheel.

And these calls for “evidence” are undermined by their very lack of terminological and conceptual consistency – and disinterest in existing knowledge. To further complicate things, researchers and scholars who could potentially debunk the novelty myth may lack incentives to do so, as with the novelty narrative comes the prospect for increased visibility and funding.

But an immediate way out of such a situation seems unlikely. An embargo on the creation of new terms – or assigning new meanings to existing ones – would be neither enforceable nor productive, let alone democratic. Maybe the same would be true for attempting to establish a broad convention around a common vocabulary. But recognition by those working in the field that the individual incentives for such a terminological carnival may be offset by the collective benefits of a more consistent and accurate vocabulary would be a first step.

In the meantime, a minimal willingness to connect with existing knowledge would help a lot, to say the least.