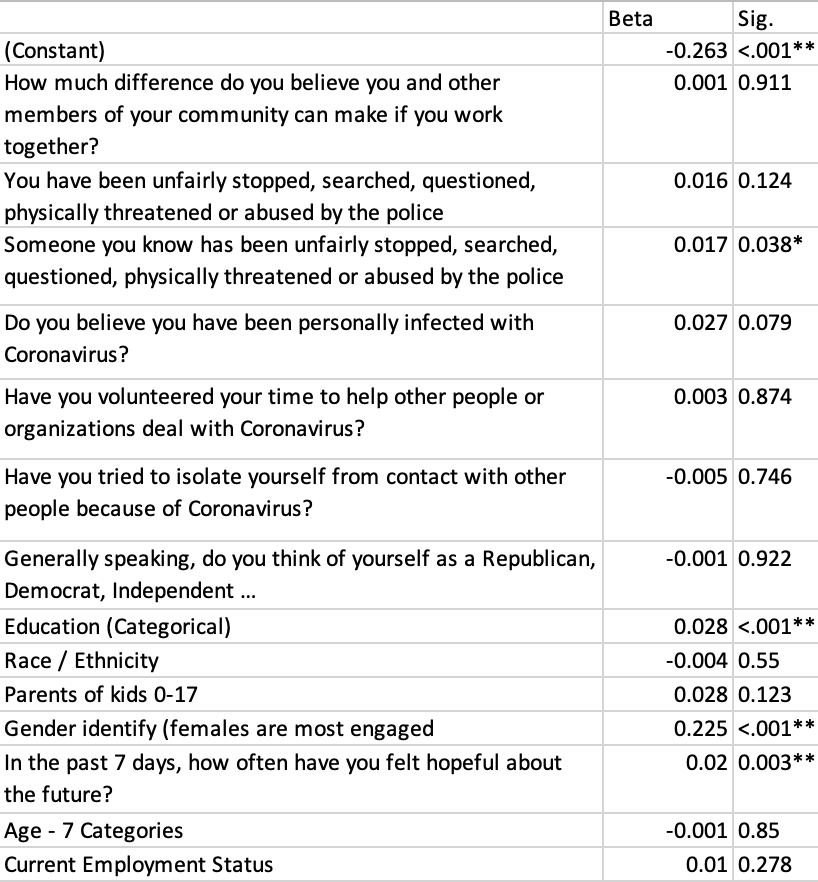

According to data from the Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC), about 130 million Americans between the ages of 16 and 74 cannot read beyond the fourth-grade level. The graph shows the distribution (where level 3 = fourth grade).

Taken at face value, this statistic has troubling implications for politics (as well as economics, health, and other matters). It does require some caution, however.

First, especially for adults, literacy is very heterogeneous or multidimensional. It’s easy to imagine that one adult could manage the King James Version, a different one could interpret instructions for installing an HVAC system, and a third could enjoy reading a thriller.

Texts present diverse challenges. The Bible can be forbidding unless you are familiar with its vocabulary and cadences from sermons. The Associated Press’ “inverted pyramid” style begins each news story with the latest developments and then explains the broader picture several paragraphs later. This is off-putting for people who have not been following the story, even if their vocabulary is good. For instance, I have paid zero attention to the Johnny Depp trial and don’t happen to know who Amber Heard is, which makes the breaking news stories actually a bit hard for me to understand. Yet my job involves reading hard texts all day.

Sample items from the PIAAC are here. They are appropriately diverse, but mostly oriented to work or news. There would be no way to design a fully comprehensive adult literacy assessment or to score it on only one metric.

Second, some texts are unnecessarily hard to read. US ballot initiatives are scandalously dense. (Compare the Brexit referendum, which asked, in full, “Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?”) The inverted pyramid style is problematic, and good explanatory journalism is too scarce. Many academics write impenetrably. (Including me: why did I use “impenetrably” instead of “badly?”)

Third, we live in a profoundly audiovisual culture, and you can obviously learn an enormous amount from sound and images. Nor are books necessarily preferable. Leaving aside children’s books, the best selling book in the US last year was a right-wing screed, Mark R. Levin’s American Marxism, which is worse than much TV and radio. In Russia in the 1990s, 39% of all publications were related to the occult, which is hardly a sign of rigorous review. (On the other hand, people who learn a lot from sound and images ought to be able to perform well on the PIAAC assessment.)

Despite these caveats, I’m worried not only that a lack of conventional literacy blocks the flow of valuable information but also that it may be alienating. Imagine that the government, reporters, medical professionals, and others keep sending messages that you literally cannot read. That is not a basis for trust.

We already accept that literacy for children is a public need. To be sure, we don’t succeed with all children, and there are complex questions about why good learning experiences aren’t consistently available for all youth. But no one doubts that the issue merits attention. Adult literacy is also important. Even if we suddenly made K-12 schools work well for all our youth, we would still have about 130 million Americans over school age who cannot score above 3 on the PIAAC.

Adults cannot (and should not be) compelled to do anything to improve their own literacy. But there is a case for much more attractive adult learning opportunities–not only as a path to better jobs but also in the interest of democracy. In my idea world, adult civic education would be literacy education, and vice-versa.

See also a way forward for high culture; separating populism from anti-intellectualism; a German/US civic education discussion; etc.