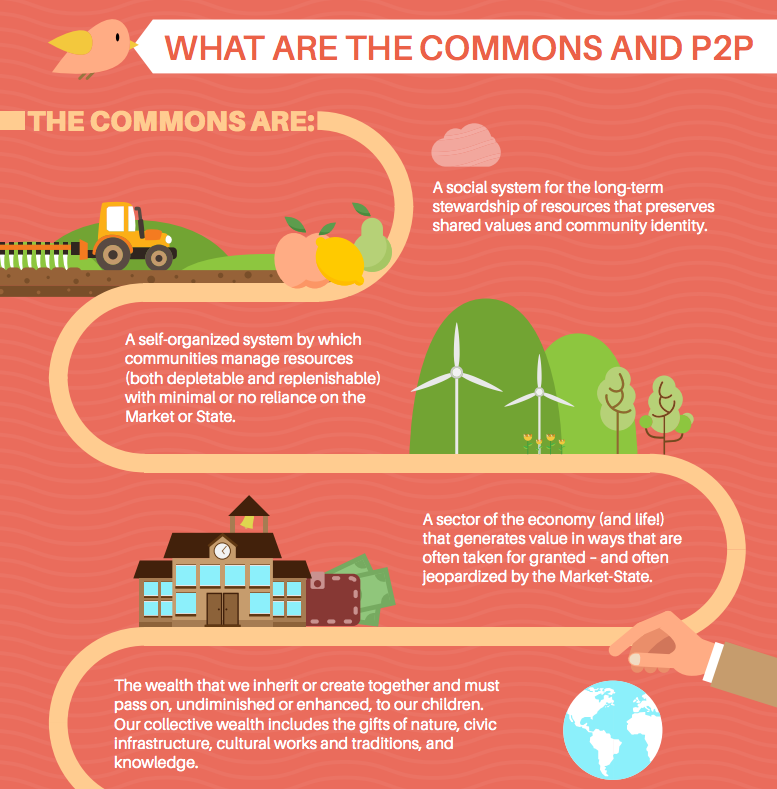

That said, even digital commoners must be able to prevent powerful market players from simply appropriating their work for commercial purposes, at no cost. Digital commoners should not simply generate “free resources” for larger market players to exploit for private gain. That is why some digital communities are exploring the use of the newly created Peer Production License, which authorizes free usage of digital material for noncommercial and commons-based people but requires any commercial users to pay a fee. Other communities are exploring the potential of “platform co-operatives,” in which an networked platform is owned and managed by the group for the benefit of its members.

The terms by which a commons protects its shared wealth and community ethos will vary immensely from one commons to another, but assuring a stable, benign relationship with markets is a major and sometimes tricky challenge.

During the last years we saw a boom in digital-commons, developed in urban areas by collectives and hack labs. What are the potentialities for non-digital commoning in the city in its present form – heavily urbanized and under constant surveillance? Are its proportions incompatible with the logic of the commons or the social right to the city is still achievable?

There has been an explosion of urban commons in the past several years, or at least a keen awareness of the need and potential of self-organized citizen projects and systems, going well beyond what either markets or city governments can provide. To be sure, digital commons such as maker spaces and FabLabs are more salient and familiar types of urban commons. And there is growing interest, as mentioned, in platform co-operatives, mutually owned and managed platforms to counter the extractive, sometimes-predatory behaviors of proprietary platforms such as Uber, Airbnb, Taskrabbit and others.

But there are many types of urban commons that already exist and that could expand, if given sufficient support. Urban agriculture and community gardens, for example, are important ways to relocalize food production and lower the carbon footprint. They also provide a way to improve the quality of food and invigorate the local economy. As fuel and transport costs rise with the approach of Peak Oil, these types of urban commons will become more important.

I might add, it is not just about growing food but about the distribution, storage and retailing of food along the whole value-chain. There is no reason that regional food systems could not be re-invented to mutualize costs, limit transport costs and ecological harm, and improve wages, working conditions, food quality (e.g., no pesticides; fresher produce), and affordability of food through commons-based food systems. Jose Luis Vivero Pol has explored the idea of “food commons” to help achieve such results, and cities like Fresno, California, are engaged with re-inventing their local agriculture/food systems as systems.

Other important urban commons are social in character, such as timebanks for bartering one’s time and services when money is scarce; urban gardens and parks managed by residents of the nearby neighborhoods, such as the Nidiaci garden in Florence, Italy; telcommunications infrastructures such as Guifi.net in Barcelona; and alternative currencies such as the BerkShares in western Massachusetts in the US, which help regions retain more of the value they generate, rather than allowing it to be siphoned away via conventional finance and banking systems.

There are also new types of state/commons partnerships such as the Bologna Regulation for the Care and Regeneration of Urban commons. This model of post-bureaucratic governance actively invites citizen groups to take responsibility for urban spaces and gardens, kindergartens and eldercare. The state remains the more powerful partner, but instead of the usual public/private partnerships that can be blatant ripoffs of the public treasury, the Bologna Regulation enlists citizens to take active responsibility for some aspect of the city. It’s not just government on behalf of citizens, but governance with citizens. It’s based on the idea of “horizontal subsidiarity” – that all levels of governments must find ways to share their powers and cooperate with single or associated citizens willing to exercise their constitutional right to carry out activities of general interest.

In France and the US, there are growing “community chartering” movements that give communities the ability to express their own interests and needs, often in the face of hostile pressures by corporations and governments. There are also efforts to develop data commons that will give ordinary people greater control over their data from mobile devices, computers and other equipment, and prevent tech companies from asserting proprietary control over data that has important public health, transport, planning or other uses. Another important form of urban commons is urban land trusts, which enable the de-commodification of urban land so that the buildings (and housing) built upon it can be more affordable to ordinary people. This is a particularly important approach as more “global cities” becomes sites of speculative investment and Airbnb-style rentals; ordinary city dwellers are being priced out of their own cities. Commons-based approaches offer some help in recovering the city for its residents.

Why bring the commons to the management and governance of a city? Urban commons can also reduce costs that a city and its citizens must pay. They do this by mutualizing the costs of infrastructure and sharing the benefits — and by inviting self-organized initiatives to contribute to the city’s needs. Urban commons enliven social life simply by bringing people together for a common purpose, whether social or civic, going beyond shopping and consumerism. And urban commons can empower people and build a sense of fairness. In a time of political alienation, this is a significant achievement.

Urban commons can unleash creative social energies of ordinary citizens, who have a range of talents and the passion to share them. They can produce artworks and music, murals and neighborhood self-improvement, data collections and stewardship of public spaces, among other things. Finally, as international and national governance structures become less effective and less trusted, cities and urban regions are likely to become the most appropriately scaled governance systems, and more receptive to the constructive role that commons can play.

Contemporary struggles for protection of commons seem to be strongly intertwined with ecological matters. We can clearly see this in struggles like the one that is currently taking place in North Dakota. Is there a direct link between the commons and ecology?

Historically, commoning has been the dominant mode of managing land and even today, in places like Africa, Asia and Latin America, it is arguably the default norm, notwithstanding the efforts of governments and investors to commodify land and natural resources. According to the International Land Alliance, an estimated 2 billion people in the world still depend upon forests, fisheries, farmland, water, wild game and other natural resources for their everyday survival. This is a huge number of people, yet conventional economists still regard this “subsistence” economy and indigenous societies as uninteresting because there is little market-exchange going on. Yet these communities are surely more ecologically mindful of their relations to the land than agribusinesses that rely upon monoculture crops and pesticides, or which exploit a plot of land purely for its commercial potential without regard for biodiversity or long-term effects, such as the massive palm oil plantations in tropical regions.

Commoning is a way for we humans to re-integrate our social and commercial practices with the fundamental imperatives of nature. By honoring specific local landscapes, the situated knowledge of commoners, the principle of inalienability, and the evolving social practices of commoning, the commons can be a powerful force for ecological improvement.

What should be the role of the state in relation to the commons?

This is a very complex subject, but in general, one can say that the state has very different ideas than commoners about how power, governance and accountability should be structured. The state is also far more eager to strike tight, cozy alliances with investors, businesses and financial institutions because of its own desires to share in the benefits of markets, and particularly, tax revenues. I call our system the market/state system because the alliance – and collusion – between the two are so extensive, and their goals and worldview so similar despite their different roles, that commoners often don’t have the freedom or choice to enact commons. Indeed, the state often criminalizes commoning – think seed sharing, file sharing, cultural re-use – because it “competes” with market forms of production and stands as a “bad example” of alternative modes of provisioning.

Having said this, state power could play many useful roles in supporting commoning, if it could be properly deployed. For example, the state could provide greater legal recognition to commoning, and not insist upon strict forms of private property and monetization. State law Is generally so hostile or indifferent to commoning that commoners often have to develop their own legal hacks or workarounds to achieve some measure of protection for their shared wealth. Think about the General Public License for software, the Creative Commons licenses, and land trusts. Each amounts to an ingenious re-purposing of property law to serve the interests of sharing and intergenerational access.

The state could also be more supportive of bottom-up infrastructures developed by commoners, whether they be wifi systems, energy coops, community solar grids, or platform co-operatives. If city governments were to develop municipal platforms for ride-hailing or apartment rentals – or many other functions – they could begin to mutualize the benefits or such services and better protect the interests of workers, consumers and the general public.

The state could also help develop better forms of finance and banking to help commoning expand. The state provides all sorts of subsidies to the banking industry despite its intense commitment to private extraction of value. Why not use “quantitative easing” or seignorage (the state’s right to create money without it being considered public debt) to finance the building of infrastructure, environmental remediation, and social needs? Commoners could benefit from new sources of credit for social or ecological purposes – or a transition to a more climate-friendly economy — that would not likely be as remunerative as conventional market activity.

For more on these topics, I recommend two reports by the Commons Strategies Group: “Democratic Money and Capital for the Commons: Strategies for Transforming Neoliberal Finance through Commons-based Alternatives,” about new types of commons-based finance and banking (http://commonsstrategies.org/democratic-money-and-capital-for-the-common...); and “State Power and Commoning: Transcending a Problematic Relationship,” a report about how we might reconceptualize state power so that it could foster commoning as a post-capitalist, post-growth means of provisioning and governance. (http://commonsstrategies.org/state-power-commoning-transcending-problema...)

How essential is, in your opinion, direct user participation for practices of commoning? Can the management of the commons be delegated to structures like the state or are the commons essentially connected to genuine grassroots democracy?

Direct participation in commoning is preferred and often essential. However, each of us has only so many hours in the day, and we can remember the complaint that “the trouble with socialism is that it takes too many evenings.” Still, there are many systems, particularly in digital commons, for assuring bottom-up opportunities for participation along with accountable governance and transparency. And there are ways in which commons values can be embedded in the design of infrastructures and institutions, much as Internet protocols favor a distributed egalitarianism. By building commons principles into the structures of larger institutions, it can help prevent or impede the private capture of them or a betrayal of their collective purposes.

That said, neither legal forms or nor organizational forms are a guarantee that the integrity of a commons and its shared wealth will remain intact. Consider how some larger co-operatives resemble conventional corporations. That is why some elemental forms of commoning remain important for assuring the cultural and ethical integrity of a commons.

We are entering in an age of aggressive privatization and degradation of commons: from privatization of water resources, through internet surveillance, to extreme air pollution. What should be the priorities of the movements fighting for protection of the commons? What about their organizational structure?

Besides securing their own commons against the threats of enclosure, commons should begin to federate and cooperate as a way to build a more self-aware Commons Sector as a viable alternative to both the state and market. We can see rudimentary forms of this in the “assemblies of the commons” that have self-organized in some cities, and in the recently formed European Commons Assembly. I am agnostic about the best organizational structure for such work because I think it will be emergent; the participants themselves must decide what will be most suitable at that time. Of course, in this digital age, I have a predisposition to think that the forms will consist of many disparate types of players loosely joined; it won’t be a centralized, hierarchical organization. The future is a “pluriverse,” and the new organizational forms will need to recognize this reality in operational ways.

What is your vision of a commons-based society? How would it look like?

I don’t have a grand vision. I stand by core values and learn from ongoing practical lessons. We don’t know the developmental evolution that will occur in the future, or for that matter, what our own imaginations and capacities might be able to actualize. Emergence happens. Yet I do believe that commoning is far more of a default talent of the human species than homo economicus. We are hard-wired to cooperate, coordinate and co-evolve together. Especially as the grand, centralized market/state systems of the 20th century begin to implode through their own dysfunctionality, the commons will more swiftly step into the breach by offering more local, convivial and trusted systems of survival.

The transition of “commonification” will likely be bumpy, if only because the current masters of the universe will not readily cede their power and prerogatives. They will be incapable of recognizing a “competing” worldview and social order. But the costs of maintaining the antiquated Old Order are becoming increasingly prohibitive. The capital expense, coercion, organizational complexities, and ecological instability are growing even as popular trust in the market/state and its political legitimacy is declining.

Rather than propose a glowing vision of a commons-based society, I am content to point to hundreds of smaller-scale projects and movements. As they find each other, replicate their innovations, and federate into a more coordinated, self-aware polity – if we dare call it that! – well, that’s when things will get very interesting.

Interview by Antonis Brumas and Yavor Tarinski

Paula Z. Segal, an attorney who works with the Urban Justice Center in New York City, explained in

Paula Z. Segal, an attorney who works with the Urban Justice Center in New York City, explained in Paula Z. Segal, an attorney who works with the Urban Justice Center in New York City, explained in

Paula Z. Segal, an attorney who works with the Urban Justice Center in New York City, explained in