Patterns and forms are very common in the social world. In Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network, my sister Caroline Levine focuses on the four forms named in her title. She acknowledges that her list may not be exhaustive, and one form that I might add is clustering, which arises when cases congregate near a mode that is seen as normal. But certainly, her four forms are ubiquitous.

To take a very simple example: Employees A and B work at Organization C. (They are within the same bounded whole). A was hired first, has more seniority, and will retire first. (Rhythm.) A supervises B. (Hierarchy). A and B exchange information. (Network.)

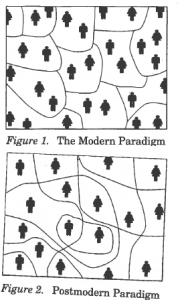

Some social theorists would argue that one of these forms is logically or temporally primary or is simply more important than the others across a wide range of cases. For instance, Marx recognized trade networks and the bounded wholes of states and classes, but for him, the key question was hierarchy: which class was dominant? Some current network theorists are eager to understand everything (including organizations’ hierarchies) as special forms of networks. But there is no a priori reason to presume that any of these forms is primary. They overlap and interact. If, within some broad domain (such as religion, or America, or postindustrial capitalism) one form is most important, that is an empirical generalization, not an analytical truth.

Why do we use certain forms to construct society?

I can imagine three mutually compatible reasons for the frequent appearance of these forms in the social world. First, they work. They have various practical advantages, or, as Caroline says, “affordances.” If you want to protect a group, then building a wall or perimeter around them can be a good idea. If you want information to flow, then a network of dirt paths or fiber-optic cables can be useful. Sometimes what people intend is irrelevant. A form just turns out to have practical value, and therefore it survives and spreads regardless of the intentions of its designers, revisers, and adopters.

Second, the same forms and patterns are very common in nature, and particularly in biology, where the study of them is known as morphology. Sometimes we imitate natural forms as we construct social phenomena.

Third, our brains may be designed to detect the forms found in nature, so that we are good at making (and also noticing) similar forms in society and culture. My dog is good at noticing bounded wholes (the perimeter of our house or any place we stay), rhythms (he expects to be fed at exactly 6:00 pm) and hierarchies (he understands himself as the lowest creature on the family’s organizational chart). But I am not sure he recognizes networks. If humans shared that limitation, then our society might not have any networks—because we couldn’t create them—or it might have networks that we couldn’t detect. And just as Barkley probably cannot see networks, we may miss forms that arise in nature or society.

By the way, we are not considering categories such as before and after or near and far that might be viewed as features of being (Aristotle) or thought (Kant). We are rather considering concrete and constructed distinctions such as inside/outside the prison or on the sabbath/on a workday. The question is not whether these distinctions are metaphysical or epistemological (or linguistic). They are social facts that we make. The question is whether they resemble similar forms in nature because lawlike tendencies govern both domains, because we choose to copy nature, or because we think that we see forms in nature that look like the forms of our social life.

Emile Durkheim navigated these waters and found himself, I would say, in roughly the right place. He held that the categories of thought had social origins. For instance, the rhythms of time with which a scientist measures biological or geological change have origins in the social rhythms of work and festivals.

But if the categories originally only translate social states, does it now follow that they can be applied to the rest of nature only as metaphors? If they were made merely to express social conditions, it seems as though they could not be extended to other realms except in this sense. Thus in so far as they aid us in thinking of the physical or biological world, they have only the value of artificial symbols, useful practically perhaps, but having no connection to reality….

But when we interpret a sociological theory of knowledge in this way, we forget that even if society is a specific reality it is not an empire within an empire; it is a part of nature, and indeed its highest representation. The social realm is a natural realm which differs from the others only by a greater complexity. …. The fundamental relations that exist between things … cannot be fundamentally dissimilar in the different realms. [The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life, trans. J.W. Swain, 1915]

Thus, by building and interpreting social structures that involve boundaries, rhythms, hierarchies, and networks, we gain the vocabulary and conceptual apparatus to attain real understanding of similar forms in nature.

Value judgments of social forms

One thing that we do—and nature does not—is to make value judgments about the instantiations of the various forms. For instance, if A supervises B, we may judge that wise and fair, unfortunate but necessary, or oppressive. If A and B belong to the same organization, but C does not, we may likewise judge that arrangement to be desirable, acceptable, or unjust. And of course, we can broaden the lens, making judgments not about A and B but more generally about employment, organizations, states, and markets. Asked why we make any of these judgments, we may cite a whole range of relevant value considerations: equity, liberty, desert, obligation, virtue, precedent, and more.

We could think of each judgment as a tag or descriptor applied to the case under consideration, but here is where I see my own recent work on moral networks as relevant. After all, our various judgments are connected. They form structures of their own.

In fact, it has often been noted that moral judgments can take the form of bounded wholes. All lies are unethical, Kant argued—putting a boundary around a large set of cases.

It has also often been noted that moral judgments can be placed in hierarchies. J.S. Mill began On Utilitarianism: “From the dawn of philosophy, the question concerning the summum bonum, or, what is the same thing, concerning the foundation of morality, has been accounted the main problem in speculative thought, has occupied the most gifted intellects, and divided them into sects and schools, carrying on a vigorous warfare against one another.” Highest goods and foundations are metaphors of hierarchy. For Mill, the principle of utility was supposed to govern our other moral ideas, much as the leader of an organization directs her employees.

And it has often been noted that moral thought, which has extension in time, involves rhythms. You sow what you reap; punishment follows the crime. Far more complex moral rhythms can be found in novels and works of narrative history.

I am interested in adding moral networks to the other three types of moral forms (boundaries, hierarchies, and narratives), because I believe that we connect our specific moral ideas to others in numerous meaningful ways. We see causation, implication, similarity, and other relations between pairs of moral ideas; and the result is a complex network that has interesting network features (centrality, modularity, gaps). But this way of thinking about morality does not exclude the categories of wholes, rhythms, and hierarchies. In fact, often the ideas that we connect together into networks are claims about boundaries; portions of our networks take the form of hierarchies; and our networks evolve over time.

So now we see at least four formal types (the keywords in Caroline’s title) playing out in at least three domains: nature, society, and ethics. Moreover, those three domains are intimately linked. Durkheim already explored how biological and social forms connect. I would add that moral judgments are closely and reciprocally connected to social forms. B accepts A’s supervision because both believe that A has an obligation to guide B. (Then the social form gains its power from its perceived moral significance.) A stranger who independently criticizes their arrangement must have learned to make her judgments as a social being enmeshed in her own wholes, rhythms, hierarchies, and networks. (Her moral structure has a social origin). She thinks that B should be liberated from A’s oversight because she has observed a different society in which people are not so supervised. (Her moral norm derives from analysis of an actual social structure). And so on.

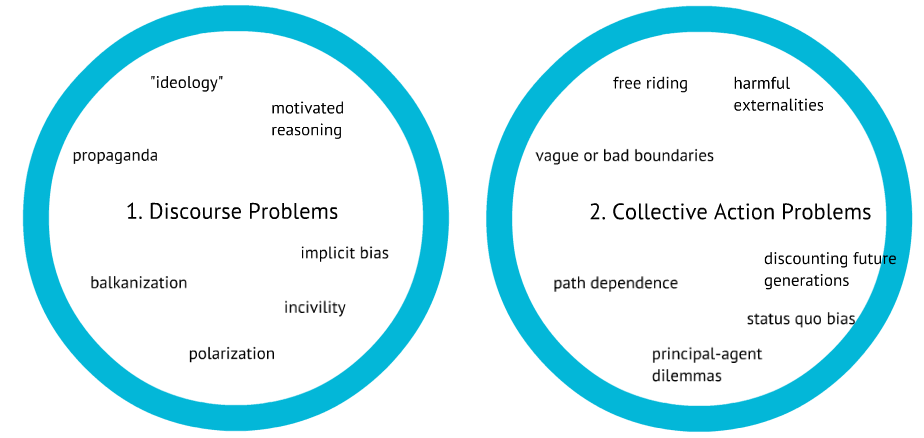

Moral judgment deals with emergent and evolved natural and social realities rather than simple categories and scenarios. Social realities are complex because millions of diverse people have constructed them over long periods and under conditions of imperfect communication, collective-action problems, path-dependence, incomplete information, mixed motives, etc. Hardly any societies look neatly designed.

If we make value judgments based on rough heuristics and instincts that our ancestors acquired millennia ago in simpler social situations, we are poorly prepared to deal with this complexity. To the extent that our instincts guide us, we are prone to serious error. But instincts may not guide us to the degree that it appears if one studies moral psychology by asking subjects their gut reactions to stylized cases, such as out-of-control trolley cars. What we actually do all day is to navigate complex, overlapping social forms. We may be a bit better at that task than current psychological data suggests.

Implications for structure and agency

Learning to make better moral judgments is then a matter of interpreting complex, overlapping forms—not only social structures but also moral ones. I am interested in solitary methods for improving that analysis, such as literally mapping our own networks of moral ideas and looking for formal strengths and weaknesses.

But we have grave cognitive limitations, so moral learning is intrinsically social and cumulative. Durkheim again:

Collective representations are the result of an immense co-operation, which stretches out not only into space but into time as well; to make them, a multitude of minds have associated, united and combined their ideas and sentiments; for them, long generations have accumulated their experience and their knowledge. A special intellectual activity is therefore concentrated in them which is infinitely richer and complexer than that of the individual.

This seems correct as far as it goes, but it can imply that individuals really don’t have much agency or choice and we cannot achieve intentional social improvements. Consider this passage from Talcott Parsons’ An Outline of the Social System (1961):

… As the source of his principal facilities of action and of his principal rewards and deprivations, the concrete social system exercises a powerful control over the action of any concrete, adult individual. … The patterning of the motivational system in terms of which he faces this situation also depends upon the social system, because his own personality structure has been shaped through the internalization of systems of social objects and of the patterns of institutionalized culture. This point, it should be made clear, is independent of the sense in which individuals are concretely autonomous or creative rather than “passive” or “conforming,” for individuality and creativity are, to a considerable extent, phenomena of the institutionalization of expectations.

Although Parsons denied he was dismissing agency, this passage certainly seems to. But we can look at the same phenomena another way. Some social systems reflect accumulated, collaborative learning. They do not just exist and control us; we have made them, working together and expressing our diverse values and interests. They are also responsive to our further learning.

To the extent that we persuade ourselves that existing patterns are all-powerful, we renounce our capacity and obligation to change them. The opposite view has been staked out by Roberto Mangabeira Unger, who argues in False Necessity that the analysis of society in terms of inflexible structures arbitrarily blocks our freedom. Unger takes “to its ultimate conclusion” the thesis “that society is an artifact” (p. 2). All our institutions, mores, habits, and incentives are things that we imagine and make. Unger “carries to extremes the idea that everything in society is politics, mere politics”–in the sense of collective action and creation (p. 1). According to Unger, even radical modernists have assumed that some things are natural, although we can actually change them. Importantly, radicals have assumed that the relations between one domain (or type of form) and another are given. For instance, for Marxists, the economy is fundamental and it always determines politics. Unger thinks we can change any part of the picture. He wants to get rid of all “superstitious inhibitions.”

I am drawn to Unger but worry that his mechanical model overlooks the degree to which a society is like an organism: sensitively interconnected and not so easy to retool without doing unanticipated damage. In any case (and here Unger would agree), social systems differ in the extent to which they embody and enable collaborative learning.

Caroline uses the depiction of Baltimore in HBO’s series The Wire as an exemplary analysis of overlapping social forms, which it is. And Baltimore (as depicted in The Wire) does reflect some democratic agency and learning—more so than North Korea would, even though North Korea could also be interpreted as a pattern of human-made boundaries, hierarchies, networks, and rhythms. But even if Baltimore is better than North Korea, it is far from optimal as a venue for democratic learning because of poverty, violence, racism, and bad institutional design.

In The Public and its Problems, John Dewey wrote (p.158), “philosophy [once] held that ideas and knowledge were functions of a mind or consciousness that originated in individuals by means of isolated contact with objects. But in fact, knowledge is a function of association and communication; it depends upon tradition, upon tools and methods socially transmitted, developed, and sanctioned.” Nevertheless, said Dewey, we need not continue doing what we have done so far. We can ask whether we should change our political system. As Hilary Putnam Putnam writes in “The Three Enlightenments” (from “Ethics without Ontology”):

For Dewey, the problem is not to justify the existence of communities, or to show that people ought to make the interests of others their own [that much is natural and unavoidable]; the problem is to justify the claim that morally decent communities should be democratically organized. This Dewey does by appealing to the need to deal intelligently rather than unintelligently with the ethical and practical problems that we confront.

To conclude: we must analyze any social situation for its formal patterns. We must make value judgments about those patterns. Our value judgments are also patterned, so we should reflect on their structure, not only on each opinion by itself. Finally, we must ask whether these patterns (in the social world and in our own thought) permit human agency and desirable change. Effective and responsible agency is not solitary but requires deliberation with people different enough from ourselves that their perspectives challenge and expand ours, but close enough to us that we can build new structures with them using the shared material at hand. In turn, that requires certain political and social conditions, which we must work to attain.

The post social criticism as reading social forms appeared first on Peter Levine.

opment of this approach. So far, we have asked individuals to name their own beliefs, given them back their lists, asked them to note which pairs of beliefs seem connected, and generated network maps of their beliefs and connections. I’ve also asked individuals to share their maps with peers and to consider making changes in response to other people’s arguments. I have mapped the ideas of multiple people as one network. Instead of using surveys, one could interview people or groups about their moral thinking on a given topic and identify the beliefs and connections implied by their speech–or use a rich text,

opment of this approach. So far, we have asked individuals to name their own beliefs, given them back their lists, asked them to note which pairs of beliefs seem connected, and generated network maps of their beliefs and connections. I’ve also asked individuals to share their maps with peers and to consider making changes in response to other people’s arguments. I have mapped the ideas of multiple people as one network. Instead of using surveys, one could interview people or groups about their moral thinking on a given topic and identify the beliefs and connections implied by their speech–or use a rich text,