You know that amazing 1977 science video Powers of Ten? If you haven’t seen it, go ahead and take a minute to watch it at the link. It might blow your mind.

Okay, well, maybe not, but this was just about my favorite movie when I was in elementary school.

I found myself thinking back to this video today after an engaging conversation with some of my colleagues about the power and role of network analysis.

With the advent of the Internet and especially of social media, the idea of “social networks” has entered – or become more prominent – within the popular lexicon.

These social networks have always existed, of course, but they now seem easier to navigate and quantify. In Facebook terms, I can tell you exactly how many friends I have, and I can also occasionally discover when two people – whom I know from different networks – know each other.

Perhaps more interestingly, the ghost in the Facebook machine has a birds eye view of everyone’s network. Not only am I individually acutely aware of the vast network of people who exist beyond my own, local network, but one could chart the social networks of everyone on Facebook as one giant, global network.

So, that’s pretty cool.

But of course, a social network of this type isn’t the only kind of network governing our world. In a social network, the people are nodes and the relationships between them are edges.

But we could zoom out a level – see where the powers of ten video comes in – and think about a community, not as a network of individuals, but a network of institutions and organizations.

And you could think of these institutional networks at different levels as well. The city I live in has a dense network of organizational ties, but we could also move outwards to look at regional organizational ties, or state-wide ties. We could look at national or international networks of relationships.

We could look at communication networks, transportation networks, relational networks, and many other types of networks operating at these macro levels.

And of course, we can zoom in as well. Thinking of an individual not as a node in a network, but as the network.

In a very literal sense, this could be the network of veins and arteries, the network of nerves, or other biological networks that keep us alive and functioning.

But we can also consider a person’s ideas as a network.

David Williamson Shaffer does this in his work on Epistemic Games. Professional training, he argues, is essentially the process of developing a specialized way of thinking – a network. A lawyer may have to learn many facts and figures, but more deeply, they learn an approach. A way to address and explore new problems.

Not only can you model this networked way of thinking in professionals, you can watch a network develop in novices.

Perhaps an individual’s morals can also be conceived as a network. This is certainly more appealing than concerning a set list of rules to follow – situations are, after all, complex and context in everything.

(While I’ll leave my zooming there, I do feel compelled to clarify that I don’t mean that to imply that we have reached the fundamental particles of human existence. I prefer to think of morals as complex, uncertain things rather than a simple, discrete point.)

So if you zoom in that far, if you consider a network where a person’s ideas are nodes – does that individual network have any connections beyond the person who contains them?

Perhaps.

Ideas are more free than blood cells, and just because I have an idea doesn’t mean you can’t have it to.

An idea may be a node within my network, but I am a node within a human network. I am a node within social networks and I am a node within institutional networks. Local institutions and, ultimately, global institutions, too – though you may not be able to spot my blip on that network map.

And that’s why I like the Powers of Ten video. Because all these different levels, all these different ways of looking at things – they’re not isolated. It’s no accident that atoms make stars.

And it is not only understanding each level that matters, it is understanding how all these levels are connected. How they build to form a whole that looks radically different from its component parts.

Understanding a single network is valuable, but understanding the levels of networks, and the network between them – well, that, my friends, would be a thing of beauty.

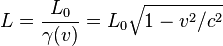

Where L is the observed length, L0 is the length at rest, v is the relative velocity between the observer and object, and c is the speed of light.

Where L is the observed length, L0 is the length at rest, v is the relative velocity between the observer and object, and c is the speed of light.