Twice in 2017 (for family reasons), we visited Uganda with stops in Dubai. I posted a longer reflection on the two societies last February and would stand by those observations after a second visit. Having just returned, I would like to emphasize a point about Uganda’s being a genuine republic–and what that word means.

Uganda’s parliament recently voted to amend the constitution so that President Yoweri Museveni can run for a sixth term (while extending MPs’ terms from five to seven years). These are probably bad decisions–not that anyone would ask my opinion–but the debate reflects Uganda’s genuine republicanism.

Here I follow Philip Pettit in understanding a republic as a system without arbitrary command. In a republic, no citizen can tell another citizen “Because I said so.” To make a society a republic, neither equality nor freedom (in the sense of private choice) must necessarily be maximized. Instead, domination–anyone’s ability to dictate what others do–must be minimized. This ideal can be accomplished by a combination of rule of law, democratically accountable institutions, certain kinds of actual equality, and a civic culture in which dominating behavior is shunned and the respectful exchange of reasons is prized.

Note that this ideal has deep African roots. In exploring the value of consensus in traditional African societies, Kwasi Wiredu emphasizes that it doesn’t mean agreement. “It suffices that all parties are able to feel that adequate account has been taken of their points of view in any proposed scheme of future action or coexistence.” In a republic, some win and some lose–and some may even lose quite consistently–but everyone’s opinions are owed consideration and a response.

Uganda ranks 125th in the world in economic equality. It is also deeply poor, which means that everyone except the elite is very badly off. The UNDP estimates that “70.3 percent of the population …. are multidimensionally poor while an additional 20.6 percent live near multidimensional poverty.” This means that very few Ugandans have cooking fuel, toilets, water or electricity that comes near their homes, a floor, any accumulated assets, or any support for their children’s education. (The government spends $2.12 per student per year on education.)

The effects of deep poverty on both political voice and actual freedom cannot be overstated. You’re not free (in most senses of the word) if your survival depends on constant physical labor, good luck, and fair treatment by those who have more than you. Meanwhile, Uganda has a problematic democracy, dominated by the majority NRM party and its president and afflicted by corruption. These are real challenges, and being a republic doesn’t compensate for them.

Yet Uganda is a republic. The constitution guarantees right to citizens. The overwhelmingly powerful NRM can amend the constitution in its own interest but still feels compelled to offer citizens reasons for its actions. Courts still review the process. Citizens still respond with very active criticism. The press is full of passionate, concerned, critical voices. There’s huge turnout at MPs’ public meetings in their constituencies. Although preserving abstract, procedural rights would seem remote on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs–a luxury or “First World Problem”–Ugandans take changes to their constitution personally.

In turn, powerful Ugandans address their fellow countrypeople as citizens. That word is common in the pronouncements of politicians, clergy, and experts. Even President Museveni feels compelled (or moved?) to address his people as citizens. While we were there, he wrote a column in New Vision, one of the newspapers that struck me as more friendly to his government. It is a somewhat digressive piece, rather like an impromptu speech after a meal, that begins with his retelling a local folk tale. He writes, “I want to inform the reader that when I read the Nyabihoko story, I was reminded of what I normally observe from the helicopter the People of Uganda provided me as President for quick travel.” He then begins to discuss various waterways in the country. But notice that he feels the need to justify his helicopter and to thank The People for it. He doesn’t have a right to a helicopter because he is the president; he needs it and feels obliged to explain why he uses one.

Uganda’s republicanism is especially notable in contrast to Dubai, where human development is dramatically higher and most people enjoy considerable actual freedom in the form of an ability to choose what to do. Moreover, the dominant cultural style is that of mass consumer capitalism, which involves treating the customer or client respectfully and not saying, “Because I said so.” A visitor with cash–a mizungu, in East African parlance–could more easily dominate people in Uganda than in Dubai, because Ugandans very badly need a customer or a tip, whereas a shopkeeper in Dubai can wait for the next person on line. Still, underlying the whole system in Dubai is “domination” in Pettit’s sense: the Ruler can decide which freedoms to permit and owes no justification.

What to make of a combination of republican norms, deep poverty, and one-party dominance? One view would be this is not really a republic. Too many Ugandans are too economically vulnerable to be able to escape everyday domination, and the NRM has too many seats (293 out of 426) for its political power to be constrained. I’d be inclined to say, instead, that Uganda faces deep economic and political challenges but still has a genuine republic, and that is an achievement for which Ugandans deserve full credit.

See also: do we live in a republic or a democracy? avoiding arbitrary command and Dubai, Uganda, and today’s global political economy.

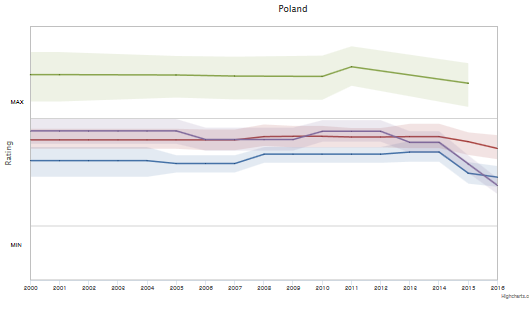

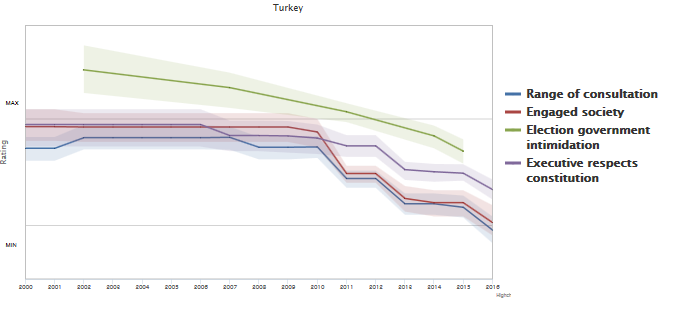

The pattern is less pronounced but similar in Poland since 2011.

The pattern is less pronounced but similar in Poland since 2011.