Not long ago, a friend asked me why anyone would want to engage in politics for politics’ sake. We worry about such things because we have to, but wouldn’t it be better, in some theoretical, ideal world, if we didn’t have to?

Imagine, for a moment, a perfect world; a society so flawless that it was always just and fair without any need for engagement from its citizens. In such a world, people would have no need for the frustrating practice of politics – they would be free, instead, to devote their time to more productive endeavors.

Now, such a thought experiment immediately raises all sorts of practical concerns; but let’s for a moment put those aside and assume that such an ideal society is both attainable and sustainable. In such a world, what would the role of citizens be?

In thinking about this question, it seemed natural to turn to John Dewey, philosopher, educator, and unwavering proponent of what he called the Great Community . Dewey’s 1927 book, The Public and It’s Problems defended democracy and responded directly to the skeptical critique of Walter Lippmann.

You’ll note here a subtle shift in language – is the thought experiment one of politics or one of democracy? Much lies, I suppose, in the definitions of these terms, but I’ll borrow here from Dewey in detangling them:

We have had occasion to refer in passing to the distinction between democracy as a social idea and political democracy as a system of government. The two are, of course, connected. The idea remains barren and empty save as it is incarnated in human relationships. Yet in discussion they must be distinguished. The idea of democracy is a wider and fuller idea than can be exemplified in the state even at its best. To be realized it must affect all modes of human association, the family, the school, industry, religion.

To be clear, Dewey had little loyalty to the specific mechanisms of political democracy:

There is no sanctity in universal suffrage, frequent elections, majority rule, congressional and cabinet government. These things are devices evolved in the direction in which the current was moving, each wave of which involved at the time of its impulsion a minimum of departure from antecedent custom and law. The devices served a purpose; but the purpose was rather that of meeting existing needs which had become too intense to be ignored, than that of forwarding the democratic idea.

So, if ‘politics’ is simply the act of engaging in a narrow system of political democracy whose mechanisms randomly sedimented over time, it’s unclear that Dewey would have much zeal for the idea of politics as an essential element of human life.

However, ‘politics’ can also be interpreted through the wider lens of democracy as a social idea; a concept to which Dewey was deeply committed.

For Dewey, democracy wasn’t a set of systems or an inventory of regulations; it was a way of life:

Regarded as an idea, democracy is not an alternative to other principles of associated life. It is the idea of community life itself.

In this sense, ‘politics’ is the very element which transforms the “physical and organic” stuff of “associated life” into the moral entity of community. The work of politics is the work of building the Great Community:

We are born organic beings associated with others, but we are not born members of a community. The young have to be brought within the traditions, outlook and interests which characterize a community by means of education…Everything which is distinctively human is learned…To learn to be human is to develop through the give-and-take of communication an effective sense of being an individually distinctive member of a community; one who understands and appreciates its believes, desires and methods, and who contributes to a further conversion of organic powers onto human resources and values.

Importantly, Dewey argues that the two senses of politics cannot exist separately; without the broader understanding of social democracy, the mechanisms of political democracy reduce to nonsense: Fraternity, liberty and equality isolated from communal life are hopeless abstractions.

It is only through the engagement of the people in this deeper politics, in democracy as a way of life, that we can ever achieve the mechanisms of political democracy we strive for.

If, some how, the ideal world described above were possible – if justice rained from the sky with no effort from below; such a society would still be lacking in the moral concept of democracy writ large.

Dewey was under no illusion that transforming the mechanisms of political democracy would be an easy undertaking – but it was a transformation he believed could only occur through the political work of the Great Community:

The highest and most difficult kind of inquiry and a subtle, delicate, vivid and responsive art of communication must take possession of the physical machinery of transmission and circulation and breathe life into it. When the machine age has thus perfected its machinery it will be a means of life and not a despotic master. It had its seer in Walt Whitman. It will have its consumption when free social inquiry is indissolubly wedded to the art of full and moving communication.

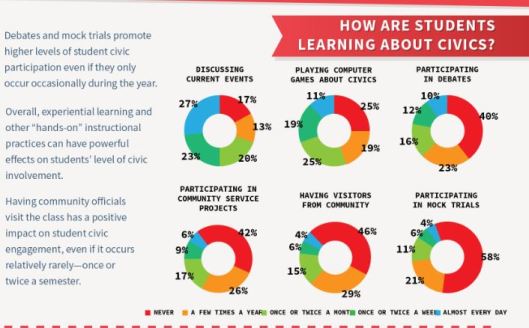

This is, perhaps, no surprise. The more students are engaged in the practices of civic life through classroom instruction, the more they are likely to engage in the practices of civic life outside of the classroom. Of course, there are caveats that must be taken into account when considering this data. For example, it is highly unlikely that 10% of students are taking part in debates every day. I do not find it surprising however that 40% of students said that they NEVER engage in debate in the classroom, and that 58% of students never participate in a mock trial (though students in Florida are SUPPOSED to experience the jury process. See SS.7.C.2.3—Experience the responsibilities of citizens at the local, state, or federal levels) . In my experience, some teachers are uncomfortable with the structure of debates and simultations and the possibility that there could be controversial (and possibly job-threatening, especially in a state with no tenure) topics involved. And of course, there is the time factor!

This is, perhaps, no surprise. The more students are engaged in the practices of civic life through classroom instruction, the more they are likely to engage in the practices of civic life outside of the classroom. Of course, there are caveats that must be taken into account when considering this data. For example, it is highly unlikely that 10% of students are taking part in debates every day. I do not find it surprising however that 40% of students said that they NEVER engage in debate in the classroom, and that 58% of students never participate in a mock trial (though students in Florida are SUPPOSED to experience the jury process. See SS.7.C.2.3—Experience the responsibilities of citizens at the local, state, or federal levels) . In my experience, some teachers are uncomfortable with the structure of debates and simultations and the possibility that there could be controversial (and possibly job-threatening, especially in a state with no tenure) topics involved. And of course, there is the time factor!