In physics, it is common to tackle complex problems by starting with a simplification of the scenario.

Want to understand how an object move along a surface? Start in a world with no friction. Assume a standard downward force, g, and understand the simplest version of what is going to occur.

Once you have a simple formula for the simple situation, then you can add friction and other real-world complications. Little by little you can expand your simple model into a complex model, slowly but surely adding the detail that’s needed to understand how things really work.

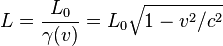

This is one of the beautiful things about the mathematics of science. When you truly come to understand the equations, you can see how clearly g, the force of gravity on Earth, is derived from G, the gravitational force of the universe. You can see how the formula for an object traveling at the speed of light is actually just the same as an object moving at an every day speed – it’s just that for every day purposes the complex factors become so small they are irrelevant.

There is nothing wrong with the world without friction. This model is a crucial first step for deeper understanding. It’s the place you have to start, the model you have to truly understand before you can move forward.

It is not uncommon to criticize the social sciences for their lack of a predictive model. Physics can describe the future trajectory of a moving object, why can political science describe the future trajectory of a government.

Frankly, I don’t find that concern all that compelling. I am rather relieved that social sciences can’t predict my every move, and I am dismayed as a matter of principle at big data analytics which seem to move in that direction.

But, from my vantage point far outside these fields, the social sciences do seem to be stuck in – or perhaps, slowly moving out of – a world without friction.

I’ve been glad to see the growth of network analysis within the social sciences. Still in its nascent stages, perhaps, but slowly adding the complexities of reality onto social science models.

People interact with each other. Organizations interact with each other. Organizations, governments, and yes, even corporations, are made of people interacting with each other.

A government doesn’t exist in a vacuum. There is – as we well know – friction within our society. Using network analysis to get at these more subtle interactions is a critical step in moving social science understanding beyond the simple – but valuable model – of a world with no friction.

Where L is the observed length, L0 is the length at rest, v is the relative velocity between the observer and object, and c is the speed of light.

Where L is the observed length, L0 is the length at rest, v is the relative velocity between the observer and object, and c is the speed of light.