In The Fall of Robespierre, Colin Jones narrates the dramatic events of July 27, 1794 (9th of Thermidor in Year II, according to the revolutionary calendar) within the city of Paris. He tells the story hour by hour and then by fifteen-minute intervals for portions of the day.

The Ninth of Thermidor was not only a pivotal episode but also probably the best documented 24 hours in human history up to that point, because several security agencies were required to file regular reports, and a huge number of Parisians kept diaries and other records of the event.

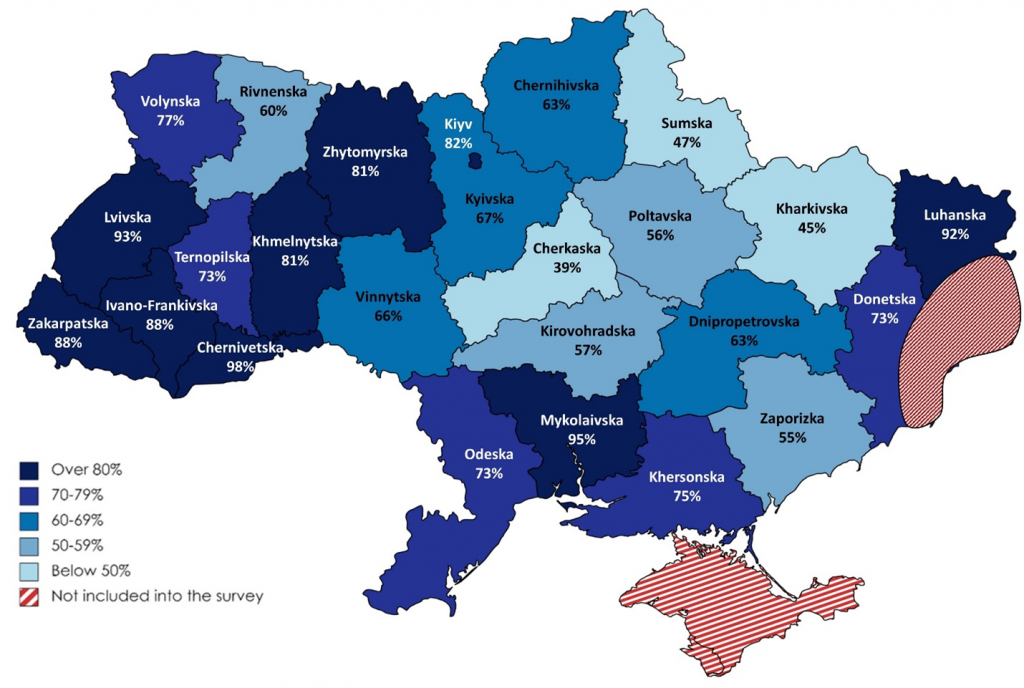

In our time, we are obsessed with communications and media technologies, to the extent that we might overestimate their importance. There is more to politics than communications. Nevertheless, Jones’ book reinforces their importance in the French Revolution and suggests certain parallels to the present, when Ukraine and Russia are waging an “information war” alongside their conventional war.

Parisians used a wide range of communications tools to convey ideas about politics. Printing presses produced daily newspapers, posters, proclamations, and even pocket-sized copies of important laws, such as the Law of 14th Frimaire, which had conferred dictatorial power on two committees. Parisians gathered daily in political bodies where they heard speeches. These venues ranged from the National Convention to the two committees that governed each of 48 neighborhood sections, not to mention the Jacobin Club and less formal gatherings. Citizens also frequented theaters, where the performances had political agendas but could be interpreted in many ways. For instance, a play about the tyrannicide Brutus might be intended to celebrate the killing of Louis XVI, yet the audience might think of Robespierre as the tyrant. Trials and daily public executions were also spectacles whose messages were not always interpreted as intended.

The ringing of bells from the buildings formerly known as churches, especially the great bell of the former Notre Dame, as well as the firing of cannons and and the beating of drums all conveyed well-known messages. Riders and pedestrian parties criss-crossed the city with handwritten documents or orders to tell people specific things. Hawkers announced the headlines of newly printed newspapers as they walked about selling them. Even the sashes, cockades, and uniforms that people wore as they moved around with such messages were communicative. For example, 9th Thermidor was first day when members of the National Convention wore elaborate prototype costumes that Jacques-Louis David had designed for them.

Parisians also found creative ways to communicate what they believed despite official censorship. My favorite tool was the fake newspaper correction, a genre of the time. One paper regretted having quoted Robespierre as saying, “It was we who made false denunciations.” According to the correction, this was just a typo, for Robespierre had really said, “It was we who silenced false denunciations.” But the journal had never published the mistake in the first place. The erratum was a way of airing the idea that Robespierre’s denunciations were false.

The events of 9th Thermidor are complex, with many independent actors. The situation crystallizes, however, by the afternoon, once the entire National Convention has voted to condemn Robespierre and his closest associates, while the Parisian city government, the Commune, has declared for Robespierre and even managed to liberate him and bring him to their building, the Hotel de Ville. Paris is essentially in a state of civil war between the national elected legislature and the municipal legislature, with both sides competing for the loyalty of a heavily armed and mobilized population.

The conflict is not ideological in a simple sense, since Robespierre’s allies and enemies alike hold heterogeneous views. In fact, Robespierre has been planning to make a sharp turn from the left to the center and right on this very day. Nor is the conflict defined by social class or other kinds of social background. Mainly, it is a matter of how people assess individuals–which ones are actually traitors?–and where they see their own interests. To turn on Robespierre if he retains power is suicidal, but to stand with him if he falls is just as dangerous.

Basically, the Convention prevails because they win the race to communicate with the most people. One key advantage is access to a large printing press; no press is located near their opponents’ HQ in the Hotel de Ville. The Commune is also frustrated in other ways. They give orders that Notre Dame’s great bell be rung in their cause, but the local assembly that controls the bell tower refuses. Meanwhile–contrary to law–some of the Parisian sections begin sending messages to the 47 other sections, creating a horizontal communications network. The same phrases begin to recur in messages from different sections, indicating that the spread is “viral.”

After the chaotic and unplanned events of the day, the question becomes how to interpret what happened. This, too, is determined by the effective use of communications media. At first, the prevailing interpretation is that Robespierre and a few confederates were caught plotting against the regime. The elected Convention plus the people of Paris stopped this threat. Policies should thus continue as before. Gradually, over the course of the year, the opposite interpretation overtakes this one. According to the new theory, the revolutionary government and the masses of Paris went off the rails until 9th Thermidor. That period is now retrospectively named “The Terror” and regarded as a tragic mistake. Robespierre’s fall along with the destruction of the Parisian Commune is seen as the beginning of a new reactionary phase, in which France must become much less radical and the people must be kept in check.

In many ways, this interpretative victory is what makes 9th Thermidor a pivotal event in French and world history–or so Jones persuasively argues.