Since publishing Doughnut Economics in 2017, renegade British economist Kate Raworth has become a phenomenon that mainstream economics largely declines to acknowledge but increasingly cannot ignore. Her book has been praised by the Pope, the UN General Assembly, and Extinction Rebellion, and translated into over 20 languages. Guardian columnist George Monbiot calls the book “brilliant, thrilling and revolutionary,” comparing it to John Maynard Keynes’ bravura General Theory book, which revolutionized economics in 1936.

Raworth’s reconceptualization of the economy as a doughnut accents two features that should be at the center of any economy: the ability to meet everyone’s basic human needs (the inner ring of the doughnut) and the ability to stay within the ecological “carrying capacity” of Earth (the outer ring).

The framework doesn’t sound so controversial. But when I spoke to Raworth for my podcast Frontiers of Commoning (Episode #15), I was astonished to learn that the economics profession, at least within the academy, has largely ignored her book despite its popularity. Scholars in development studies, political science, and architecture are keenly interested, she notes, as are countless students, activists, and city governments. The cities of Amsterdam, Copenhagen, and Brussels, among others, have actually embraced “the doughnut” as a way to guide their municipal policies and programs.

But mainstream economists “balk at the idea,” said Raworth. “They say that I’m stepping away from the scholarship and imposing my values as a political advocate.”

Raworth argues that “the doughnut” simply expresses two foundational commitments that most societies collectively share – that people have a human rights to have their basic needs met, and that the ecological stability of the planet must be protected. If those are seen as controversial values, says Raworth, let's debate them. In any case, she adds, “It’s not as if mainstream economists don’t have values embedded in what they teach. They’re just not explicit about it.”

Raworth’s impertinence about economics may stem from years of straddling the worlds of economic theory and its real-world implementation. She has worked with micro-entrepreneurs in Africa and done development work for the United Nations and Oxfam. Nowadays Raworth teaches at Oxford University’s Environmental Change Institute and at Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences as Professor of Practice.

Despite the academic affiliations, she remains focused on how to bring about economic transformation. That is the avowed mission of the Doughnut Economics Action Lab (DEAL), which Raworth cofounded in 2019 with Carlota Sanz. DEAL is an attempt to reframe economic narratives, influence strategic policy, and develop innovations with practitioners.

Doughnut Economics has the winning tendency of using spritely humor and common sense while skewering the buried half-truths of standard economics and serving up more credible alternatives. For example, economics continues to cling to the idealized notion of “rational economic man,” the fiction that people make careful, rational calculations about how to advance their material self-interests and happiness (“utility”) through market transactions.

Raworth handily debunks this point in her book, and then shows great brio in producing a delightfully clever video, “Economic Man vs. Humanity: A Puppet Rap Battle,” in collaboration with puppet designer Emma Powell and musician Simon Panbrucker. It’s safe to say that the rapping students get the best of their fusty old professor, and Raworth’s playful humor triumphs over economic dogma.

One of the biggest targets of Raworth’s "doughnut," of course, is the idea that economic growth is a magic elixir that can solve most inequalities, social ills, pollution, and even climate change. The general catechism is growth = jobs = consumer demand = market innovation = progress.

This mindset conveniently ignores the copious negative externalities of the capitalist economy and its circular faith that market-based strategies can abate market-based pathologies When US climate envoy John Kerry’s recently claimed that half of all carbon reductions needed to get to net zero will come from technologies that have not yet been invented, I realized that denialism has many faces.

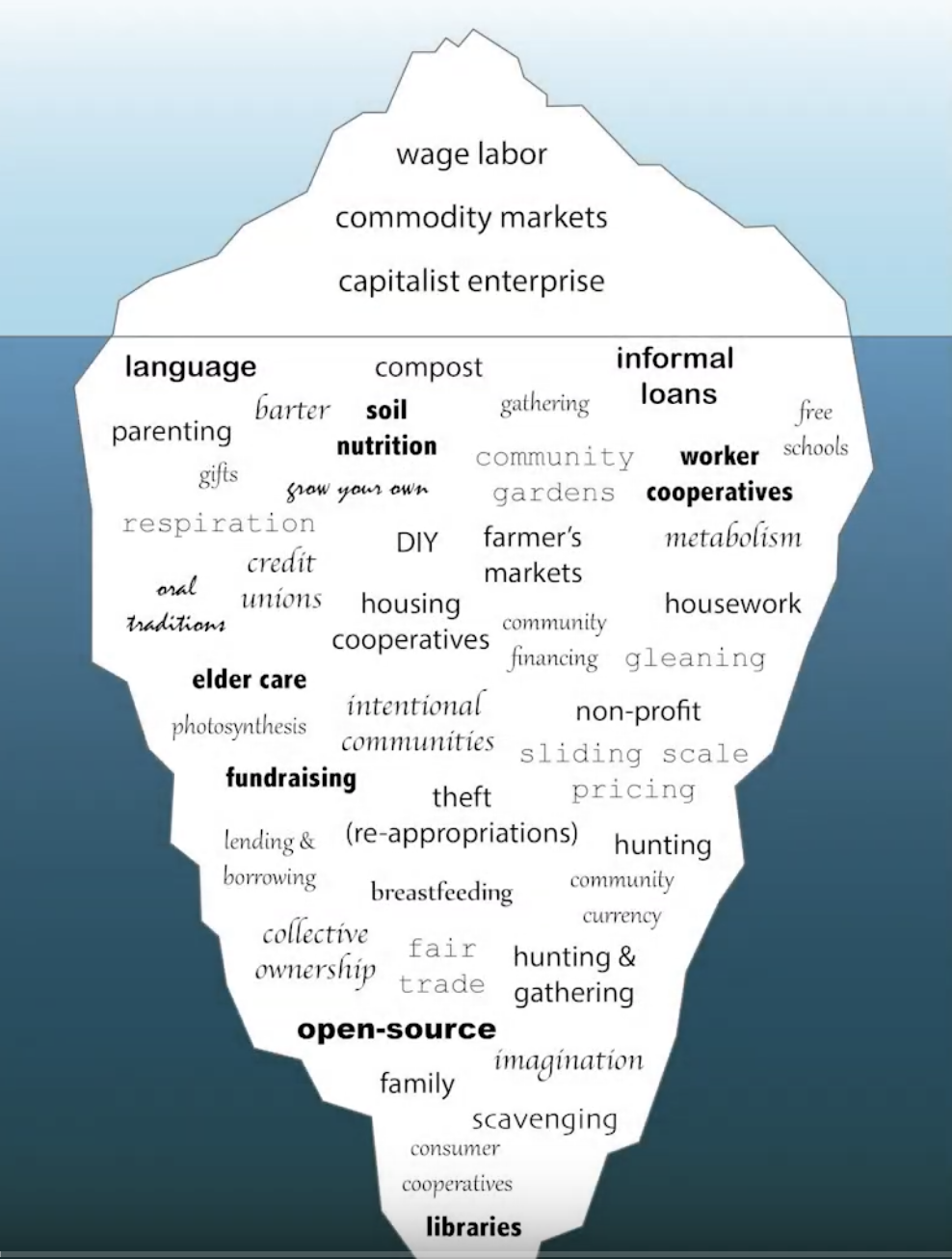

What sets apart Raworth’s approach is her insistence that society and ecology are foundational to any economy, and economic thought must reflect that. Her theoretical framework, therefore, is not fixated on market and state – important as they are -- but equally on households and the commons as essential institutions. Why? Because households and commons engender social trust, reciprocity, care, and creativity in ways that the market/state system simply cannot.

You can listen to Raworth’s conversation with me on Frontiers of Commoning here.

Crimes against property had been an essential part of the transition from feudalism to capitalism, as Linebaugh discovered. And so the “crime collective” scholars began to study highway robbery, smuggling, and piracy through the lens of sociology, history, and politics.

Crimes against property had been an essential part of the transition from feudalism to capitalism, as Linebaugh discovered. And so the “crime collective” scholars began to study highway robbery, smuggling, and piracy through the lens of sociology, history, and politics.