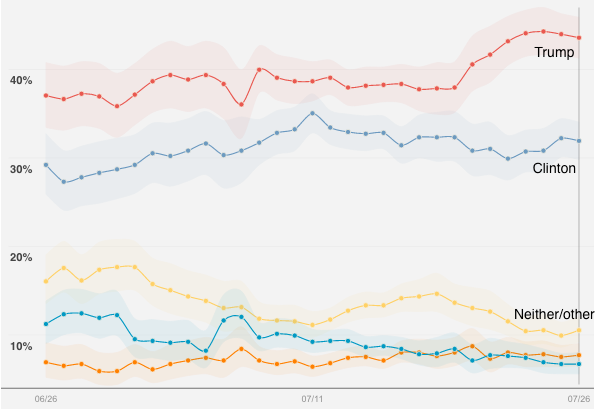

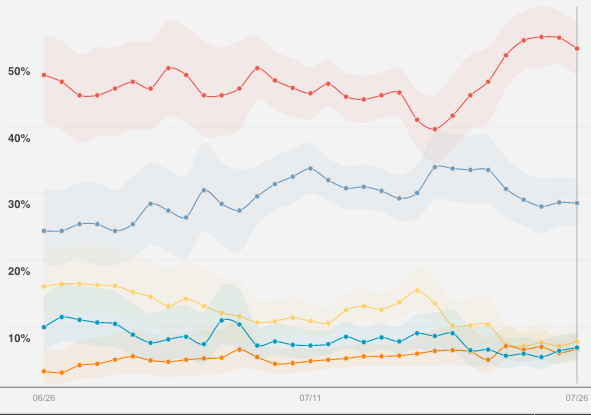

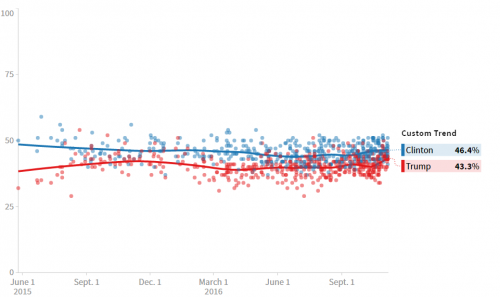

The graph below depicts the 2016 campaign as I see it. When all the polls are displayed on a graph with a y-axis from 0-100% and a fairly strong “smoothing” algorithm is applied, it becomes evident that hardly anything has changed for 18 months. Hillary Clinton has been ahead of Donald Trump by about 4-5 points nationally all along, and she leads by a mean of exactly four points in the major final polls released by this point on the last Monday. The ups and downs revealed by zooming in are best understood as temporary responses to news that may influence who participates in surveys–or who feels enthusiastic on a given day–but very few people have actually changed their minds; and most of those switches have been random and have canceled each other out.

I think this means that Clinton is likely to win the national popular vote by about 4 points, although GOTV operations could change result that (in either direction).

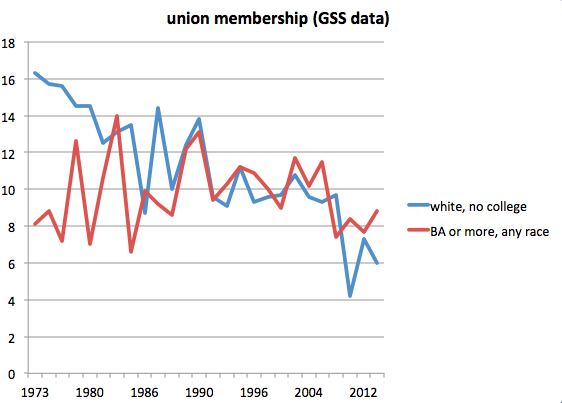

It’s hard to know whether different nominees would have performed differently. A reasonable guess is that if both parties had nominated politicians with typical levels of popularity who used typical methods of campaigning, the Republican would have an edge. That implies that Trump v. Clinton costs the GOP maybe 4-6 points, net–but that is not much more than a guess.

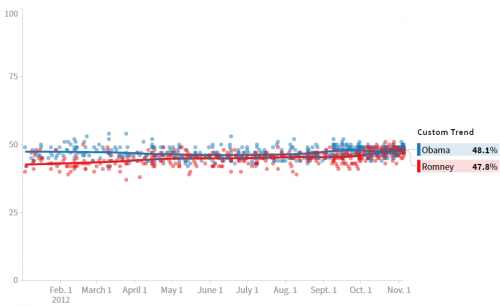

By the way, 2012 looks about the same, except Romney ran closer to Obama all the way along.

But 2008 was different: McCain was ahead at first but slipped behind Obama to lose pretty badly.

For me, the interesting question is what this means about our civic culture and the purpose of campaigns and elections. The presidential candidates have raised about $1.3 billion so far and spent most of that on such activities as advertising, canvassing, and events. The press has spent untold billions on campaign coverage and commentary. All kinds of remarkable events have occurred. As all that has played out, citizens have been exhorted to pay attention and to change their opinions in response to arguments and information. But it looks as if almost everyone already had enough data 18 months ago to make up their minds. That includes me: nothing has transpired since June 2015 that has altered the probability of my voting for Clinton versus Trump by even one thousandth of a percentage point.

I used to subscribe to the view that the actions of candidates and campaigns matter, but they usually cancel each other out because all presidential nominees of major parties are effective campaigners. This year, we have one truly incompetent candidate, yet the trend remains flat. Unless you think that Clinton’s weaknesses cancel out Trump’s incompetence, it looks as if campaigns hardly matter at all. Once citizens know the candidates’ party labels, demographics, and basic facts about their biographies, they are ready to vote.

Perhaps Joseph Schumpeter was right, at least about presidential politics. It’s all about rendering a verdict on the status quo and choosing either the incumbent elites or an outsider. Schumpeter adds:

The reduced sense of responsibility and the absence of effective volition in turn explain the ordinary citizen’s ignorance and lack of judgment in matters of domestic and foreign policy which are if anything more shocking in the case of educated people and of people who are successfully active in non-political walks of life than it is with uneducated people in humble stations. Information is plentiful and readily available. But this does not seem to make any difference. Nor should we wonder at it. … Without the initiative that comes from immediate responsibility, ignorance will persist in the face of masses of information however complete and correct. It persists even in the face of the meritorious efforts that are being made to go beyond presenting information and to teach the use of it by means of lectures, classes, discussion groups. Results are not zero. But they are small. People cannot be carried up the ladder. …

Thus the typical citizen drops down to a lower level of mental performance as soon as he enters the political field. He argues and analyzes in a way which he would readily recognize as infantile within the sphere of his real interests. He becomes a primitive again. His thinking becomes associative and affective.

Since Schumpeter’s view of democracy is unattractive, we must either reform presidential politics or (if that seems impossible) write it off and focus on other aspects of our political system, where more people can show more “immediate responsibility” for collective decisions.