Friends in Civics, it gives me great pleasure this morning to turn over this platform to Dr. Shawn Healy. Dr. Healy is the Chair of the Illinois Civic Mission Coalition, and he was a key player on the citizen-driven team that worked hard to pass legislation concerning civic education in Illinois. He joins us today to share some of the sausage making and civic activism that it took to get the state legislature to add civics as a required course for high school students. Without further ado, then, I give you Dr. Shawn Healy. Please click below the fold to read his excellent post!

On August 21, 2015, Governor Bruce Rauner signed House Bill (HB) 4025 into law, requiring that future Illinois high school students complete a semester-long civics course. Course content will center on government institutions, current and controversial issue discussions, service-learning, and simulations of democratic processes. The course mandate would take effect on July 1, 2016, and apply to incoming freshmen for the 2016-2017 school year.

What follows is a chronicle of the Illinois Civic Mission Coalition’s (ICMC) campaign for bringing civics back to high schools statewide. It fittingly borrows the ten-point framework developed by former Florida Senator Bob Graham and his co-author Chris Hand in their 2010 book titled America: The Owner’s Manual (CQ Press).

- Defining the problem: The ICMC drew upon data from recent research and reports that framed Illinois’ poor civic health and its disparate impact on youth and disadvantaged populations.

- Illinois Millennials (18-29) are less likely to vote in local elections, speak to or exchange favors with neighbors, or work within their communities to solve problems versus young people in other states.

- 70% of Illinoisans have little to no trust in state government.

- Minority and low income students have less access to quality civic education, contributing to a lifelong civic participation gap.

- The information-gathering process: The ICMC gathered information on best practices in other states, learning that Illinois was an outlier in not requiring a civics course. We also documented current course offerings without a mandate, and the impact of proven civic learning practices.

- Illinois is one of only eleven states that does not require students to complete a civics or government course in order to graduate.

- Sixty percent of Illinois high schools currently require a civics or government course; 27% offer the subject as only an elective, and 13% have no civics/government course (see Figure 1 below).

- Proven civic learning practices like current events discussions improve students’ civic knowledge, skills, and dispositions with greater dosage (See Figure 2 below).

- Identifying who in government can fix the problem: A new course mandate requires a legislative change to the Illinois School Code. The ICMC partnered with two sympathetic legislators in Chicago’s western suburbs, Rep. Deb Conroy (D-Villa Park) and Sen. Tom Cullerton (D-Villa Park) beginning in 2013 to create a statewide task force on civic education. Its principal recommendation was to require a semester-long high school civics course (read the full task force report here). Conroy and Cullerton incorporated this recommendation into a bill and shepherded it through their respective chambers in the spring of 2015.

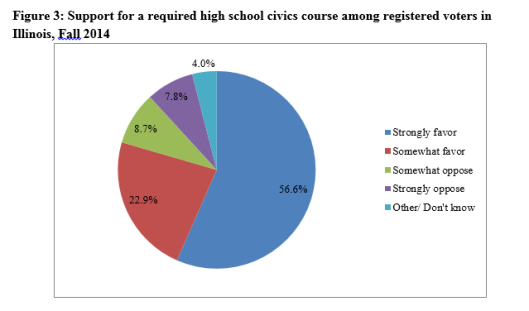

- Gauging and building public support for the cause: Thanks to a long-standing partnership with the Paul Simon Public Policy Institute at Southern Illinois University, the ICMC was able to include a series of questions in the annual Simon Poll, sampling public support for a high school civics course and project-based learning. The results revealed strong overall support that transcended partisanship, ideology, and region (See Figure 3 below).

- Persuading decision-makers: The ICMC recruited and retained a public affairs firm, Serafin & Associates, with extensive relationships in Illinois’ capitol. Together, they built strong bi-partisan support for the legislation, focusing first on the House Education Committee where the bill originated. In partnership with the bill sponsors, they pushed legislators of both parties to co-sponsor the bill, securing their votes and sending signals to their peers that they too should vote “aye” when the bill was called in committee and on the floor. In reaching out to individual legislators, the ICMC and Serafin used research on local schools’ course offerings and most successfully, educators in their districts that “schooled” them on the importance of civics.

- Using calendars to achieve goals: The urgency of the #BringCivicsBack Campaign was driven by the legislative calendar. Deadlines for filing legislation, passing bills out of committee, moving the bill through both chambers, and a sixty day window for gubernatorial consideration necessitated its resolution by the end of summer.

Amendments to the original bill complicated matters in the House of Representatives where it originated, forcing two hearings in the Education Committee. Getting the language right the first time is an important lesson learned.

The larger political context must also be accounted for. Illinois has Democratic supermajorities in both houses, but a rookie Republican Governor. Bi-partisan support was thus critical for the legislation’s ultimate success. Regardless, civic education must be broader than a single party’s political agenda. It’s integral to the long-term health of our democracy.

Like many states, Illinois is crippled by a fiscal crisis that trickles down to individual school districts. Advocating for a new school mandate in this environment was difficult and we were obligated to demonstrate that teachers, schools, and districts would be supported by a public-private partnership in implementing it with no state appropriations (see #9 below).

- Coalitions for citizen success: The Illinois Civic Mission Coalition, convened by the Robert R. McCormick Foundation, is a broad, non-partisan consortium which includes educators, administrators, students, universities, funders, elected officials, policymakers and representatives from the private and non-profit sectors. Formed in 2004 by the Constitutional Rights Foundation Chicago, the ICMC and its network of Democracy Schools provided a strong base of support for the #BringCivicsBack Campaign.

Old allies like the Illinois Council for the Social Studies, James Madison Fellows, and the League of Women Voters also contributed greatly. New champions like the education advocacy organization Advance Illinois, corporate supporters like All State and Boeing, and even Chicago Public Schools and the Chicago Teachers Union broadened the coalition and built credibility on both sides of the political spectrum.

Finally, while the Illinois Statewide School Management Alliance strongly opposed the new legislation, school board members, superintendents, and principals rallied to the cause and provided critical cover “behind enemy lines.”

- Engaging the media: Our communication team, in partnership with Serafin & Associates, did extensive media outreach at every stage of the #BringCivicsBack Campaign. We considered multiple communication channels (newspapers, radio, TV, and online) and leveraged personal relationships and networks. Among our most prominent media hits were favorable editorials in both the Chicago Tribune and Chicago Sun-Times (see Figure 4), regular radio coverage on WDCB Public Radio, and segments on WGN Radio and TV.

Our team also mobilized prominent supporters to pen letters to the editor in strategic publications aimed at targeted legislators. We shared stories extensively on social media, using the hash tag #BringCivicsBack. While we worked hard to stay on message in media interviews, we were thrown a few curveballs when our opponents lampooned the legislation. Our team quickly developed talking points in response, broadcasted them widely, and mitigated any potential fallout.

- Finding resources to support the initiative: Illinois’ legislative breakthrough was dependent upon the advocacy and financial support of my employer, the Robert R. McCormick Foundation. Our President and CEO David Hiller committed precious time and treasure to the cause and contributed greatly to the #BringCivicsBack Campaign’s success. He rallied other funders, both corporations and foundations, and helped build a $500,000 annual implementation fund on top of McCormick’s existing $1.4 million of annul investments in Illinois’ civic education system.

Hiller also built an extensive list of prominent corporate and civic supporters, placing their names on letterhead and leveraging the contacts and credibility of this impressive, bi-partisan group in outreach to legislators and the Governor alike.

10. Preserving victory and learning from defeat: While this chronicle represents a victory lap of sorts, it also reflects significant lessons learned from past defeats.

Eight years ago, the ICMC successfully pushed for passage of the Civic Education Advancement Act. It called for high schools throughout Illinois to conduct assessments of current civic learning practices and later develop improvement plans to strengthen their overall civic mission. Schools would receive $3,000 of public funding for this purpose, but the initial $750,000 appropriation from the Illinois General Assembly was line item vetoed by then Governor Rod Blagojevich.

The fiscal situation in Illinois has since deteriorated further, so the prospects for public funding for the current effort were slim and none. We therefore recognized the need for private funding to support implementation, enabling us to argue that this is a “funded” mandate.

Beyond the points expressed in the previous passages, I recommend thanking supporters at each stage of the process. Not only is it the right thing to do, but it is highly likely that you will need to ask policymakers and advocates for help again on the same campaign or another one down the road. Given the multiple amendments to our legislation and a companion bill to clarify its implementation date, we asked legislators for support repeatedly, and our previous, public thank you’s went a long way in ensuring their continued allegiance to our cause.

This lengthy chronicle attests to the importance of the exercise as it will help guide future efforts in Illinois and elsewhere as we learned from Florida, Tennessee, California, and other states that charted paths for us and others to follow.

As for preserving victory, our work on the implementation process paralleled the legislative push. Our plan is emerging and will soon be introduced publically. It will center on establishing a statewide system of teacher professional development and classroom resources, building the capacity of teachers, schools, and districts to offer transformational capstone civics courses for all of Illinois’ students.

Thank you, Dr. Healy, for this fantastic look into the activism and work that it took to pass quality and important legislation that will help students grow into the citizens we know we need. The importance of a citizen coalition that embraces all stakeholders , as well as to learn from past failures are ones that were used to similar effect here in Florida in pursuit of our own Sandra Day O’Connor Act. We look forward to hearing about implementation and how this will look in the classrooms. I believe that the importance of media cannot be understated as well, for this is how you get fellow citizens engaged and involved.

Civics matters, friends. It matters for our nation, it matters for our state, it matters for our local community. And learning what it means to be a citizen begins in two places: at home, and in school. We cannot influence what they learn at home, but we CAN make a difference in schools. We have to (though not necessarily using the US Citizenship Test. But that’s a different post!)

UPDATE (08 Sep): The Chicago Tribune has a good piece on the impact of this legislation at the ground level! (A subscription is required to read, but it’s worth the 99 cents!)